Nairobi should not exist. At least not in the way it does now. Before the 1890s, the land that would become Kenya’s capital was a swampy plain, a stretch of flat grassland with patches of marsh. The Maasai called it Enkare Nyirobi — the place of cool waters — but to British engineers building the Uganda Railway, it was a convenient midpoint between Mombasa and Kisumu. Convenience, not wisdom, is how most mistakes are made, and Nairobi is perhaps the most successful mistake in East Africa.

In 1896, the railway project was already a nightmare. Disease, hostile terrain, and the occasional lion devouring Indian workers slowed progress. By the time the line crept into the highlands, the engineers needed a central depot where they could set up workshops, rest camps, and storage facilities. They picked Nairobi in 1899. The swamp looked like trouble, but it was high enough to escape the worst of the coastal malaria, flat enough for tracks, and wet enough to promise water. What followed was less a settlement and more a muddy railway camp of tents, timber sheds, and temporary barracks.

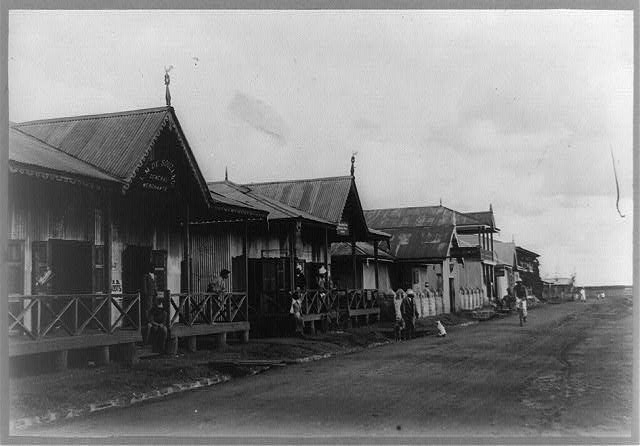

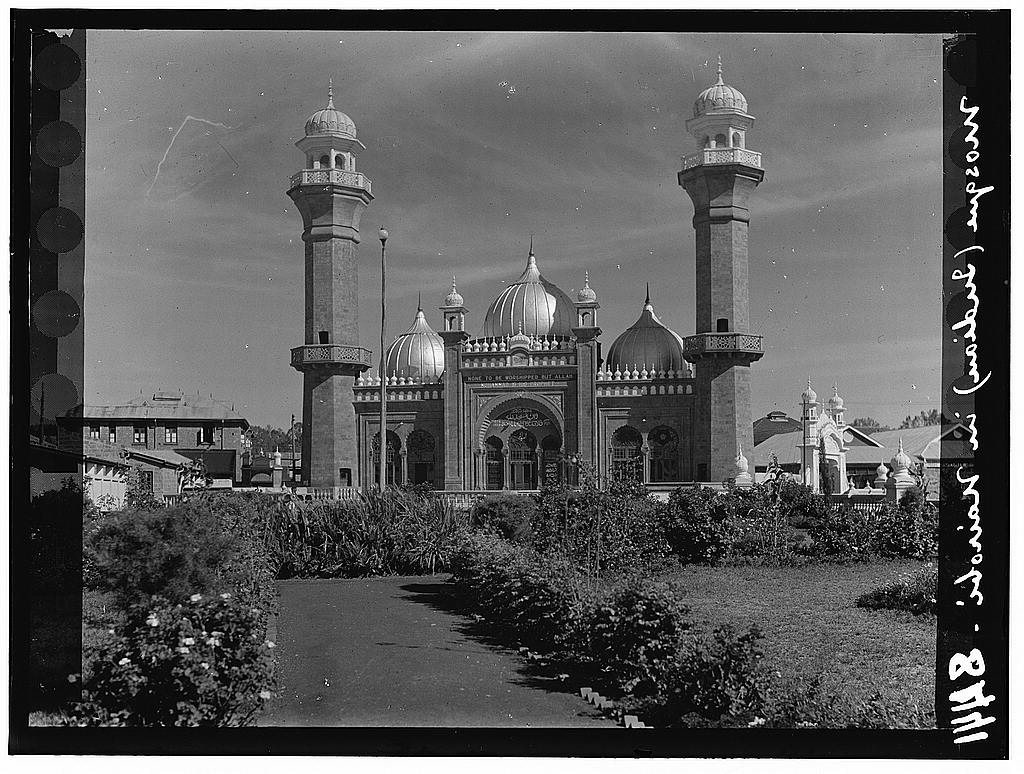

This camp grew fast. Traders, mostly Indian, pitched dukas to sell food and supplies to railway workers. African laborers — Kikuyu from the highlands, Luo and Luhya from the west — arrived looking for work, even though colonial laws kept them strictly at the margins. And wherever men gather, vice follows. Brothels sprouted almost as quickly as churches, and Nairobi’s reputation for disorder began before it even had a nameplate.

The British administrators hated it. Machakos, further east, had been the Protectorate’s administrative base, but it was too dry. Kikuyu country was greener and healthier. Nairobi was muddy, pestilent, and barely standing on its foundations. But the railway officials dug in, and the town grew too fast to ignore. By 1901, the railway headquarters had officially moved there. Four years later, in 1905, Nairobi was declared the capital of the British East Africa Protectorate. A swamp had become a capital city.

It was an unplanned birth, and it shows. Nairobi was built on expediency, not design. No master plan, no foresight, just a depot that metastasized into a city. Its problems — from flooding to congestion to corruption — are all rooted in this accidental beginning. Nairobi was never meant to be beautiful or sustainable. It was meant to serve the railway, and then it refused to stop growing.

A Playground for Settlers and Segregation

When Nairobi was crowned the capital in 1905, it was less a city than a stubborn fungus growing on colonial ambition. The railway had birthed it, but now it had to play host to administrators, settlers, traders, missionaries, and the chaos they dragged with them. To the British, Nairobi was the promise of a frontier town that could become a European oasis in Africa. To everyone else, it was a swamp where the rules bent with the convenience of whoever was in charge.

The first order of business was to make the swamp livable for Europeans. That meant segregation, dressed up in sanitary language. Europeans built their houses on higher ground — Muthaiga, Karen, Lavington — away from the mosquitoes and the mud. Asians, mostly Indian traders and workers who had arrived with the railway, were pushed into Parklands and Eastleigh. Africans, who did most of the building, cleaning, and hauling, were shoved into Pumwani and other “native locations” on the fringes. A pass system and strict curfews ensured that Africans could serve the city by day but had to retreat to its margins by night. Nairobi was a colonial town, and colonial towns thrived on exclusion.

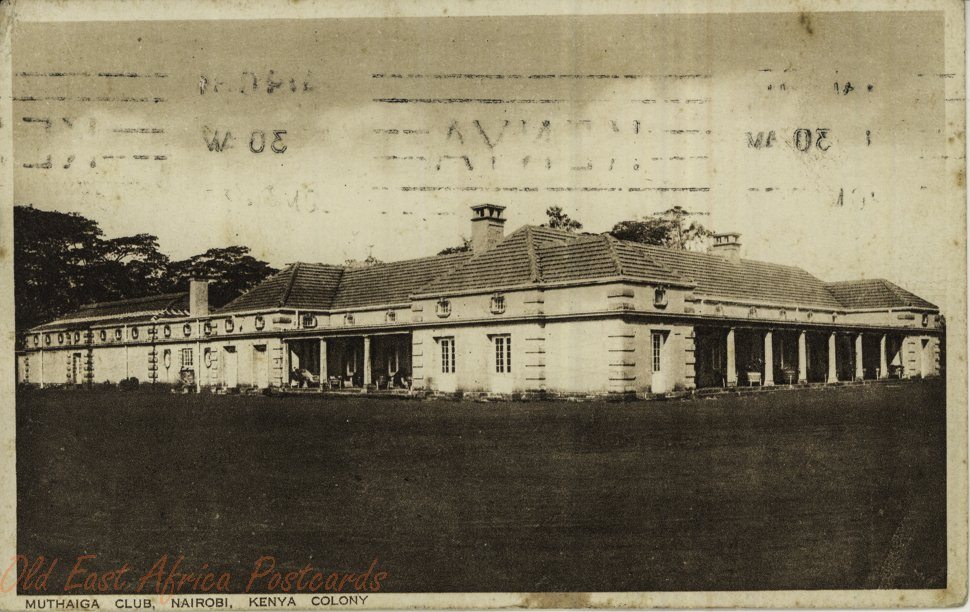

But it was not all administration and zoning. Nairobi quickly developed a reputation as the settlers’ playground. By the 1920s, the colonial elite had built the Muthaiga Country Club, a bastion of gin, polo, and scandal. The city attracted fortune seekers, aristocrats, and adventurers who treated East Africa like their personal playground. They drank heavily, gambled recklessly, and conducted affairs with each other’s spouses. In these clubs, the real business of the colony was conducted — not in offices but over whiskey and whispered deals.

This era birthed the infamous Happy Valley set, a group of European aristocrats who pushed Nairobi’s decadence into international headlines. Cocaine, opium, and wild parties blurred into gunfights and duels. The colony’s most famous scandal came in 1941, when Josslyn Hay, the Earl of Erroll, was found shot dead in his car on the outskirts of Nairobi. His murder, unsolved to this day, exposed the colony’s underbelly of vice and betrayal. For the British back home, Nairobi was no longer just an administrative outpost. It was a theatre of sin in the tropics.

Africans, of course, lived in another Nairobi entirely. Their neighborhoods were overcrowded and under-policed, yet they thrived with activity. Beer halls, dance joints, and informal markets created a parallel economy outside the colonial gaze. The authorities raided often, citing sanitation or morality, but Nairobi had already grown beyond their control. Africans were not supposed to own or belong to the city, yet they made it theirs anyway.

By the 1930s, Nairobi was no longer a railway camp. It was a city split down the middle: a manicured European enclave on one side, a buzzing African underworld on the other. And between them, the railway line that had started it all, carrying not just goods but the contradictions of a city that had grown too fast for anyone to plan.

Nationalism, Resistance, and Mau Mau in the City

By the 1940s, Nairobi had grown from a railway depot and settler playground into something far more dangerous to the colonial project: a crucible of African resistance. The British had built Nairobi to serve empire, but Africans had claimed it as their own political stage. Every strike, pamphlet, and whispered meeting in a Pumwani hall chipped away at colonial control.

The roots of urban resistance had been planted earlier by figures like Harry Thuku, one of Nairobi’s first political agitators. In the 1920s, Thuku mobilized against forced labor and heavy taxation through his Young Kikuyu Association. When he was arrested in 1922, protests erupted in Nairobi. Police opened fire on demonstrators outside the Norfolk Hotel, killing more than twenty. The colonial government tried to silence Thuku by exiling him, but they had already lit a fire. Nairobi’s African working class had discovered the power of collective action.

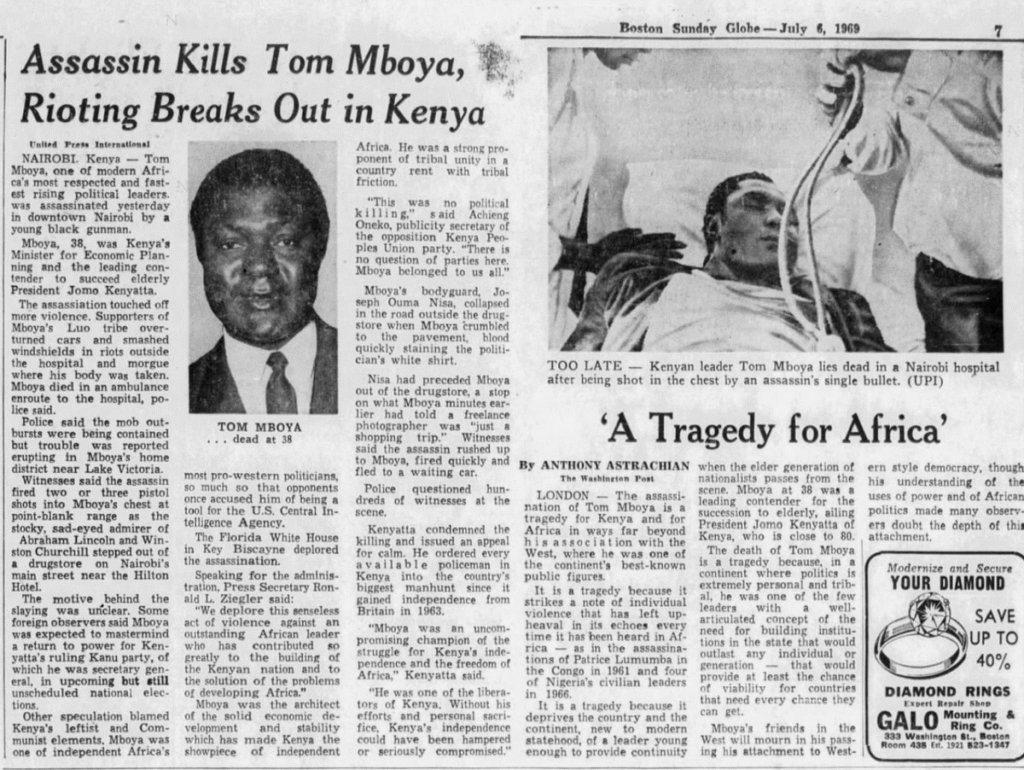

The 1940s turned that spark into flame. Africans crowded into Nairobi’s labor market, working in factories, workshops, and offices. Trade unions emerged, led by sharp young organizers like Tom Mboya, who could move a crowd with words and strategy. In neighborhoods like Kaloleni and Shauri Moyo, workers plotted strikes demanding better pay and dignity. Nairobi became a city where the African voice, long suppressed, grew too loud to ignore.

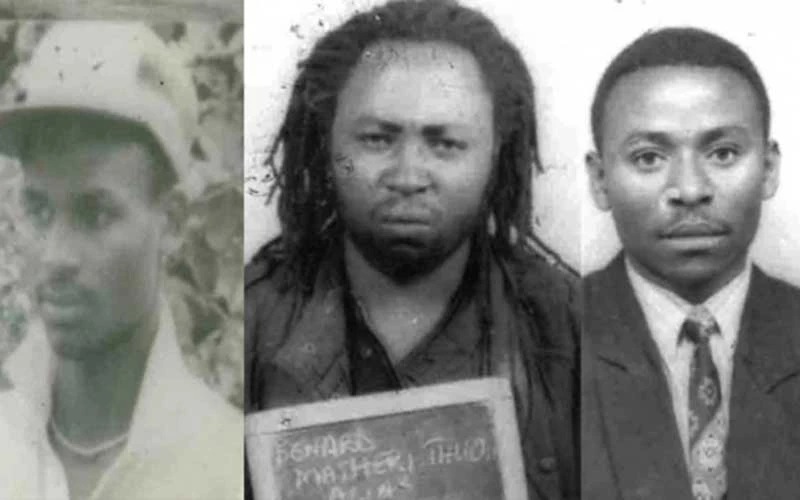

Then came Mau Mau. The rebellion is often remembered as a rural war fought in forests and mountains, but Nairobi was one of its critical fronts. Here, Mau Mau sympathizers organized secret oaths, fundraised for fighters, and smuggled weapons. The city’s streets became a battlefield of surveillance and subversion. Colonial authorities responded with brutal force.

In Operation Anvil (1954), the British military and police cordoned off Nairobi in a massive sweep. Entire African neighborhoods were raided at dawn. Thousands were rounded up, suspected Mau Mau supporters and ordinary workers alike, and herded into detention camps. The city was militarized overnight, its African population treated as a pool of suspects. Nairobi had become both the heart of resistance and the stage for colonial repression.

But repression could not erase what had been born in Nairobi’s neighborhoods: political consciousness. Every arrest, every beating, every humiliation forged a generation of activists who would demand independence. By the late 1950s, the colonial state was rotting from within, unable to contain the nationalist wave. Nairobi, once the swamp of cool waters, had become the boiling cauldron of Kenya’s freedom struggle.

Independence and the African City

When the Union Jack came down in December 1963 and Kenya became independent, Nairobi stood at the center of the celebration. The swamp that had become a railway town and then a colonial capital was now the capital of a sovereign African state. Fireworks lit the sky above Uhuru Park, and Jomo Kenyatta, once imprisoned in colonial cells, stood as Prime Minister. For the first time, Africans claimed Nairobi not as laborers or squatters, but as citizens.

But independence did not wipe the slate clean. The city carried the scars of colonial segregation, and the inequalities mapped by the Crown Lands Ordinance did not vanish with flags and anthems. The colonial elite left, but their estates and suburbs did not. They were simply inherited by the new African elite — politicians, businessmen, and bureaucrats who stepped into the shoes of settlers. Muthaiga and Karen, once restricted to Europeans, now hosted cabinet ministers and parastatal chiefs. Nairobi’s geography of privilege remained intact, only the accents at the dinner tables changed.

At the same time, the city experienced an explosion of migration. Freed from colonial pass laws, thousands of Africans poured into Nairobi from every corner of the country. They came chasing work, education, and the promise of urban life. But Nairobi was unprepared for them. Infrastructure that had been designed to serve a few thousand Europeans and Asians was suddenly overwhelmed by millions. Housing shortages grew acute, and informal settlements mushroomed around the city. Kibera, already established in colonial days as a settlement for Nubian soldiers, expanded into one of the largest slums in Africa. Mathare and Korogocho followed, testimony to the gap between national independence and urban survival.

Yet Nairobi also carried the energy of a young nation. In the 1960s and 1970s, the city became a cultural and political hub. Pan-African leaders passed through on their way to conferences. African writers gathered in Nairobi, sparking debates at the University of Nairobi and in the smoky backrooms of pubs. The “Green City in the Sun” slogan captured the optimism of the time: boulevards lined with jacarandas, modernist buildings sprouting downtown, and a growing African middle class taking its place in offices once reserved for Europeans.

But politics soon crept back into the city’s veins. Nairobi became the stage where Kenya’s post-independence struggles unfolded: ethnic rivalries, assassinations, and battles for power. When Tom Mboya, the trade unionist who had risen to become a cabinet minister, was gunned down in 1969 on Government Road (now Moi Avenue), the city erupted in grief and anger. Independence had come, but the struggle for justice was far from over.

Nairobi in the first decade of independence was a city of contradictions — hope and inequality, pride and betrayal. It was a capital claiming its African identity, but it carried the swamp’s curse of imbalance, a city always growing faster than it could govern itself.

Nairobbery, Hustle, and Survival

By the 1980s, Nairobi’s glow as the “Green City in the Sun” had dimmed. What had once been a young nation’s proud capital was now infamous for something else entirely: crime. The city earned a new nickname, whispered in matatus and shouted in foreign travel advisories — Nairobbery.

The reasons were as obvious as they were grim. Kenya’s economy faltered under debt crises and structural adjustment programs. Formal jobs dried up while the city’s population ballooned past two million. For every one person who landed a steady office job, dozens more hustled on the streets, hawking, repairing, driving, or simply surviving. The inequality was visible everywhere — skyscrapers downtown casting shadows over sprawling slums like Kibera and Mathare. Out of that imbalance grew a city where theft was not just a crime but almost an economy of its own.

Carjackings became Nairobi’s urban horror story. Armed gangs would stop cars at intersections, drag drivers out, and disappear with vehicles into the labyrinth of the city. Muggings and burglaries were so common that owning a house meant also owning a wall, a gate, and guard dogs. Even police officers, underpaid and corrupt, were both predator and prey — sometimes arresting criminals by day and partnering with them by night. Nairobi was dangerous, and everyone knew it.

But crime was only one face of Nairobi in the 80s and 90s. The other was the hustle. This was the era when matatu culture exploded, transforming public transport into a moving carnival. Matatus, once just minibuses, became canvases of graffiti art, neon lights, and thundering speakers blasting Congolese soukous, reggae, and later, hip hop. Conductors hung out of doors, shouting routes, hustling for passengers. Every ride was part transport, part theater, part fight for survival. The matatu became Nairobi’s most honest reflection: loud, chaotic, corrupt, but undeniably alive.

Politics added another layer of danger and drama. Nairobi became the beating heart of resistance against Daniel arap Moi’s one-party state. Pro-democracy activists filled Uhuru Park, Kamukunji Grounds, and the streets with rallies and protests. Police responded with teargas, bullets, and mass arrests. The fight for multiparty democracy in the early 1990s turned Nairobi into a battleground, where idealism clashed with authoritarianism, and where ordinary Nairobians had to learn to duck both muggers and riot police.

Yet through it all, the city refused to collapse. Nairobians adapted. They built informal economies in Gikomba and Eastleigh, stitched together survival in markets and kiosks, and invented Sheng to make the city their own. It was a brutal period, but it was also when Nairobi became the Nairobi we know today — a place of endless hustle, where survival itself became a badge of honor.

By the end of the 1990s, Nairobi was both feared and admired. It was a city you might lose your wallet in, but it was also a city where, if you had the wit and resilience, you could build a life from nothing. In its brokenness, Nairobi had found a strange kind of identity.

Nairobi in the 21st Century — Global City, Broken City

The turn of the millennium found Nairobi at a crossroads. The city that had been written off as “Nairobbery” in the 90s began to reinvent itself as something grander: a regional hub, a magnet for multinationals, and the unlikely darling of global institutions. Yet beneath the glass towers and investor pitches, the same old swamp problems lingered.

On one hand, Nairobi was now a city of conferences and suits. The United Nations planted its Africa headquarters in Gigiri, making Nairobi one of only four cities in the world to host a major UN office. Global NGOs set up shop, turning leafy suburbs into headquarters for aid bureaucracies. Multinationals saw opportunity: banks, airlines, and tech firms made Nairobi their East African base. The skyline transformed as new skyscrapers rose in Upper Hill and Westlands, symbols of an economy trying to outgrow its colonial skeleton.

At the same time, Nairobi became the heart of Kenya’s tech boom. The rise of M-Pesa, launched in 2007, turned the city into the epicenter of what outsiders breathlessly branded the “Silicon Savannah.” Tech startups mushroomed, innovation hubs like iHub sprouted, and suddenly Nairobi was being spoken of in the same breath as Bangalore or Cape Town. For a city born in a swamp, this was a new identity: global, digital, ambitious.

But the swamp never left. Heavy rains still turned downtown streets into rivers. Informal settlements like Kibera, Mathare, and Mukuru continued to swell with migrants shut out of formal housing. Corruption ate away at infrastructure: roads crumbled months after they were built, traffic jams stretched for hours, and basic services lagged behind population growth. Nairobi was a city of gated suburbs with swimming pools next to slums without clean water. The divide was not just visible — it was unmissable.

Terrorism added another wound. The 1998 US Embassy bombing in downtown Nairobi, which killed more than 200 people, had already scarred the city. In the 21st century, Al-Shabaab attacks brought fear to shopping malls, churches, and bus stops. The Westgate Mall attack in 2013 and the DusitD2 siege in 2019 reminded Nairobians that modernity came with its own fragility.

And yet, Nairobi pulsed on. The matatus got louder, the slang sharper, the hustle harder. Art and music flourished: hip hop, gengetone, spoken word at places like Kwani? and Sarakasi Dome. Nairobi became a cultural powerhouse, a city of contradictions where poets performed to packed audiences while street vendors dodged municipal raids a few blocks away.

By the 2020s, Nairobi was a paradox made flesh. It was both the “Green City in the Sun” and the choking capital of pollution and traffic. It was both the seat of global diplomacy and a place where power cuts could black out entire neighborhoods. It was both Silicon Savannah and Nairobbery, often on the same day. Nairobi had grown too big to be one thing. It was everything, all at once — broken, beautiful, and alive.

Conclusion: Nairobi’s Swamp Curse and Survival

Every city carries its birthmark. For Nairobi, it is the swamp. A century after engineers staked their tents on Enkare Nyirobi’s marshy plain, the city still floods with every heavy rain. Streets become rivers, traffic stalls, and the ghosts of railway surveyors laugh in the puddles. The swamp has never left. It simply learned to wear glass and steel.

The history of Nairobi is not a neat story of progress. It is a catalogue of accidents, improvisations, and contradictions. A railway depot that became a capital. A colonial playground that became a crucible of resistance. A crime-ridden mess that somehow became a global hub. Nairobi is a city that survives by refusing to obey the rules of planning or logic.

It has always been a city of divides. Europeans on the hills, Africans in the swamps. Later, ministers in Karen, hawkers in Gikomba. Skyscrapers for the rich, shanties for the poor. These divides have shifted but never disappeared, etched into the geography as stubbornly as the swamp itself.

And yet Nairobi endures. It is a city of hustlers, and hustle is the closest thing to a religion here. From the matatu driver with neon lights and a subwoofer, to the tech startup pitching apps in Kilimani, to the mama mboga stacking sukuma in Gikomba, Nairobians have turned survival into an art form. That art has kept the city alive when it should have drowned in mud, crime, or corruption.

The swamp’s curse is also its gift. Nairobi is unstable, unpredictable, and unfinished — but that is what makes it alive. It is a city that should not exist, and yet it refuses to stop growing. A mistake that became a metropolis. A mess that became a miracle.

Nairobi is not the city you dream of. It is the city that dares you to wake up and fight. And in that fight, in that daily dance with chaos, lies its strange, enduring beauty.