The Empire’s Steel Dream

In the late 19th century, British colonial planners set their sights on a grand infrastructure project that sounded like pure madness to many: a railway from the Indian Ocean coast deep into the East African interior. The idea was born from imperial ambition during the Scramble for Africa, as Britain vied with other European powers for territory and influence. Uganda, with the headwaters of the Nile, was especially strategic – controlling it meant securing the Nile (and by extension the Suez Canal and Egypt) from rival powers. But how to reach this landlocked prize? The answer was a railway stretching some 580 miles from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria, through unmapped wilderness, malarial swamps, and hostile highlands. Skeptics in London were aghast at the cost (estimated at £5 million) and the seemingly little immediate economic return. British MP Henry Labouchère famously mocked the venture in a satirical poem, marveling that “what it will cost no words can express… it clearly is naught but a lunatic line.” Thus was born the nickname “The Lunatic Line,” a moniker for an enterprise that many thought had derailed into folly even before a single rail was laid.

Yet for all the ridicule, the British Empire’s will prevailed. In 1896, construction of the Uganda Railway (ironically named, since nearly its entire length ran through what is now Kenya) began at Mombasa’s Kilindini Harbour. For colonial officials, this railroad was the key to “opening up” East Africa – a steel snake to slither into the interior and tame it for trade and settlement. Interestingly, local African lore had long prophesied such an intrusion: various Kenyan tribes spoke of an “iron snake” that would one day cross the land, bringing foreigners and great upheaval. To the Maasai, Kikuyu, Kamba and others, the coming of the railway was literally foretold as an omen of trouble, “with as many legs as a centipede…spewing fire” as it went. By the time the first surveyors hacked through the coastal brush, this prophecy was becoming reality. The British, however, framed the project in more optimistic (if self-serving) terms: the railway would facilitate commerce, “civilize” the hinterland, even help eradicate the slave trade by displacing the old slave-caravan routes. With these lofty justifications, London signed off on the enormous expense. The Empire’s steel dream was officially under way – and about to demand an equally colossal human sacrifice in sweat and blood.

Recruiting the ‘Coolies’

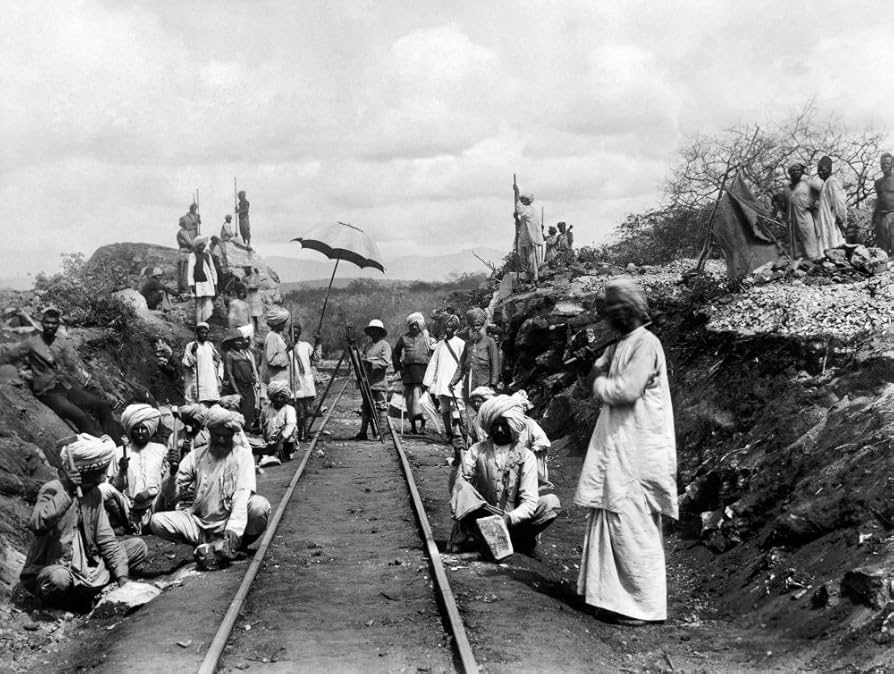

Building the “iron snake” across East Africa was not a job many volunteered for – at least not locally. Early attempts to conscript or hire indigenous African labor met with stiff resistance and hostility, as communities understandably balked at the foreign project intruding on their lands. Faced with this challenge and eager to cut costs, British administrators turned to a solution they had used throughout their empire: imported indentured labor. They looked across the ocean to British India, which had a large pool of workers experienced in railway construction and used to toiling under imperial contracts. In 1895, an enterprising Parsi merchant named Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee won the contract to recruit labour for the Uganda Railway. By the following year, a steady stream of Indian labourers – derogatorily called “coolies” by the British – began arriving in Mombasa. Over the course of construction (1896–1901), roughly 32,000 Indians were recruited from the subcontinent to work on the line. The principal recruiting center was Lahore in Punjab; from there, thousands of desperate men from villages in Punjab and beyond were herded onto trains to Karachi, then onto steamships bound for Mombasa.

The vast majority of these workers were young men, mostly Sikhs and Punjabis, seeking to escape poverty or earn a modest stake abroad. They signed up for three-year contracts, lured by the promise of regular wages (however meager) and free passage back after the job. Many left their families behind, assuming they would return home once the railway was done. It was a gamble: they were headed to a land they didn’t know, for an employer that viewed them as cheap, expendable muscle. British colonial officials considered Indians more “reliable” and stronger workers than the locals, not to mention more accustomed to British rule. By March 1901, the number of Indian “coolies” on the project peaked at nearly 20,000 men on site at once. They labored in grueling conditions, living in tent camps that leap-frogged forward with the railhead, from the sweltering coast into the highlands. For their effort, a typical worker might earn around 12 annas (three-quarters of a rupee) a day – barely enough to send a few rupees home each month. The work was hard and perilous, but in the colonial calculus these men were cheap. As one historian wryly noted, British policy replaced enslaved African labor with indentured Indian labor in many colonies post-abolition – “cheap” lives to expend for imperial projects. And so they came by the thousands, armed with pickaxes, hammers, and hope, to carve the Lunatic Line through what newspapers back in Britain liked to call “darkest Africa.” Little did they know just how much darkness – literal and figurative – they would face on those remote Kenyan plains.

Blood on the Tracks

From day one, building the Uganda Railway was an extreme exercise in human endurance. The terrain itself seemed hostile to the idea of a railroad. Workers hacked through dense mangrove swamps along the coast under a punishing sun. Further inland, they blasted and chiseled their way up the Tsavo Valley and into the highlands, often with little more than hand tools and dynamite. Nature fought back ferociously. Malaria and dysentery swept through the camps, felling workers by the hundreds. At one point, sleeping sickness carried by tsetse flies in the Kibwezi area caused so many fatalities that an entire camp had to be abandoned. Exact figures are elusive, but by the end of the project approximately 2,500 labourers had perished – roughly four deaths for every mile of track laid. Month after month, as many as 38 workers on average died – a grim drumbeat of loss accompanying the advance of steel. “Because of the line’s increasing financial burden, British officials sought to cut costs wherever possible, including labour relations,” notes one account dryly. In practice this meant scant medical care, flimsy shelter, and relentless pressure to meet construction targets despite the peril. The result was predictable: men succumbed to heat exhaustion, disease, and accidents at an appalling rate.

Then came the lions. In March 1898, as the railhead reached the Tsavo River, workers began falling prey to something in the night. Distant screams in the darkness, bodies dragged from tents – a terror stalked the camps. It turned out to be two man-eating lions, exceptionally large and maneless male lions, that developed a taste for railway workers. For about nine months, these bold predators treated the construction camps as an all-you-can-eat buffet, snatching men from their tents with chilling audacity. “Night after night, Indian laborers were seized and devoured,” one recollection describes, as the workforce was gripped by panic. The project’s chief engineer, Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, attempted to hunt the beasts even as they hunted his workers. The attacks grew so frequent that construction virtually halted for three weeks – workers refused to go out, and some fled Tsavo altogether, preferring to risk their jobs than certain death. Official British reports later claimed the Tsavo lions killed 28 workers, but Patterson himself estimated they killed 135 men – likely an exaggeration, but indicative of the terror they inspired. Contemporary analyses suggest “dozens” of victims is a fair estimate, with some modern research putting the number around 35 based on lion hair and bone isotopes (grisly science). Whatever the exact toll, the legend of the “Man-Eaters of Tsavo” was born, soon to be embellished in British parlors and American museums (the two lion skins now reside, stuffed, in the Field Museum in Chicago). Patterson finally shot the first lion in December 1898 and the second a few weeks later, ending the immediate nightmare. But by then, the “blood on the tracks” was more than just a figure of speech. Between savage wildlife, rampant disease, and innumerable on-the-job accidents (from dynamite blasts, falls, floods, and even the occasional rhino attack), building the railway had become a veritable war against nature. The British goal was achieved – by 1901 the line had reached Kisumu (Port Florence) on Lake Victoria – but at a terrible human cost. As one Kenyan museum display now soberly notes, the Uganda Railway was “a colossal engineering feat that transformed East Africa forever,” but it “came at a profound cost” in lives and suffering. Those steel rails were tempered with sweat and stained with the blood of thousands, mostly nameless and forgotten by history.

A Railway, a Colony, a Community

On a drizzly morning in late 1901, a steam locomotive chugged into a makeshift station on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, heralding the completion of the Uganda Railway. The “Lunatic Line” had defied its detractors – it was finished, and with it the British had their steel artery into the heart of East Africa. In London, newspapers celebrated the engineering triumph, and colonial officials wasted no time in exploiting it. The railway had literally built a colony in its wake. Every few dozen miles along the track, where construction crews had pitched camp, little settlements sprouted – many of which would grow into Kenya’s major towns. Mombasa, the coastal terminus, was already a bustling port; but now Nairobi, which had been nothing more than a malarial swamp at the rail’s midpoint, blossomed into the administrative headquarters during construction (the railway engineers chose it for a depot in 1899). By 1905 Nairobi was named capital of the new British East Africa Protectorate – a city that “the railway helped create,” as a museum plaque notes. Indeed, a quick glance at the map of Kenya today shows that most urban centers trace their roots to railway stations or stopovers – from Voi and Tsavo, to Makindu, Nakuru, Eldoret and beyond. Steel rails now linked the hinterlands to the coast, and in doing so, laid the foundation for a modern nation’s economic geography.

When the work was done, the Indian labourers who had built the line faced a crossroads. The British had imported them as disposable workers, not prospective settlers – yet many did settle. Out of the approximately 32,000 brought over, about 6,700 decided to remain in East Africa after the railway’s completion. These were the pioneers of today’s East African Indian (or “Asian”) community. Some stayed because they had little to return to in India; others saw opportunity in the new towns sprouting along the line. They sent for relatives or married locally and transitioned from pickaxe-wielding coolies to shopkeepers, artisans, clerks, and traders. British economic policy, perhaps inadvertently, gave them an opening: the railway had opened the interior to trade, and Indian merchants were quick to take advantage. Dukas (shops) run by enterprising Indians popped up at every significant station. A legendary figure in this regard was Allidina Visram, a savvy merchant from Kutch, who during the railway construction had opened provisioning stores all along the route (he was sole supplier of food to the Indian workers on the line). After 1901, Visram expanded his enterprises, establishing dozens of shops and trading posts from Mombasa to Kisumu – by the time of his death in 1916 he reportedly had over 240 shops across East Africa. Other former railway workers found employment with the railway itself, which needed station masters, signalmen, mechanics and guards; many were happy to hire on permanently now that the line was running, not just being built. In the years that followed, Indians also staffed a growing bureaucracy and commercial sector in the Protectorate. They had one foot in two worlds – as British subjects they had more rights than Africans, but as non-Europeans they were shut out of the highest status roles. Still, this nascent community of Indian settlers established roots: they built temples, mosques, and gurdwaras; started schools and newspapers; and created social clubs and charities in the towns. By 1921, Nairobi’s population was one-third Asian, and across Kenya, Indians had become an influential minority – a community born out of the railway.

The railway itself became the lifeblood of the colony’s economy. It carried everything from cash crops and manufactured goods to passengers of all races (albeit segregated by class). It even played odd cameo roles in history, like in 1909 when former US President Theodore Roosevelt toured British East Africa on a hunting safari – riding the Uganda Railway into the wild, with dozens of porters and gun-bearers in tow, a story that made international headlines. For the Indian workers-turned-settlers, such events were less important than the everyday business of making a living in a strange new land. They navigated a colonial system that alternately relied on and resented them. Over time, many who had begun as humble railway coolies rose to become successful merchants and professionals. Alibhai M. Jeevanjee, the very man who recruited labor for the railway, settled in Nairobi and thrived – by 1904, it was said he owned half of Mombasa and much of Nairobi, and in 1910 he became the first non-white appointed to the colony’s Legislative Council. Indians established East Africa’s first printing press and newspaper (the African Standard, now The Standard, founded by Jeevanjee in 1901). Community organizations like the Mombasa Indian Association (1900) and later the East African Indian National Congress (1914) sprang up to fight for racial equality and political representation. In short, the railway not only created a colony – it also inadvertently seeded a new diaspora community in Africa. These settlers from Gujarat, Punjab, Konkani coast and elsewhere carried with them their languages, religions, and cultural traditions, adding a new thread to the tapestry of East African society.

The British Divide

For all the talk of commerce and civilization, British rule in Kenya introduced a harsh racial hierarchy – and the railway played a central role in shaping it. After 1902, once the railway was operational, the colonial government opened up the fertile highlands for European settlement. They encouraged British (and other European) farmers to come grow cash crops like tea, coffee, and sisal. These settlers were granted vast tracts in what came to be known as the “White Highlands,” lands explicitly reserved for Europeans only. This was the start of Kenya’s notorious racial segregation. The European elite sat firmly at the top of the pyramid, enjoying political power, owning huge farms, and living in segregated enclaves. Meanwhile, Indians – now often called Asians in East Africa – were mostly confined to the commercial and artisan class in towns. They could prosper in business, but they were barred from owning the prime agricultural land and faced constant discrimination from the colonists. Many Europeans regarded Indians as a convenient middleman class: useful for trade and skilled jobs, but socially inferior. One prominent settler, Lady Delamere, sneered that “to be within measurable distance of an Indian coolie is very disagreeable”, encapsulating the racist disdain many colonials held toward the very people who had built their railroad.

At the bottom of the colonial order were the Africans, in their own country yet treated as strangers or servants in the new system. The British enforced a system of pass laws and “native reserves” that kept most Africans restricted to certain rural areas unless they had work permits to be in towns. Tellingly, in Nairobi, Asians were permitted to reside and own businesses in designated areas, whereas black Africans were initially not allowed to live freely in the city at all (they were only tolerated as laborers and had to carry passes). Across Kenya, virtually everything was segregated by race: schools, hospitals, hotels, even public toilets and park benches. A British memo from the 1920s described Nairobi as “racially zoned” with separate areas for Europeans, Asians, and Africans. One Indian lawyer in colonial Kenya recalled that even the railway trains had segregated compartments – Europeans rode in first-class coaches from which Indians and Africans were excluded. The colonial capital became known derisively as the “White Man’s City” – its amenities and fine buildings largely off-limits to people of color. This systematic discrimination extended to every aspect of life. As late as the 1940s, the Coryndon Museum (today’s National Museum) in Nairobi was whites only – never mind that the land was Africa’s and that even the museum’s founding donor was an Indian trader (Alidina Visram, who funded its precursor in 1911). It took a public outcry (and a more liberal curator) in 1941 to finally open the museum to all races, and even then European patrons complained bitterly about having to share space with “smelly” Africans or “over-scented” Asians.

The British effectively stratified Kenyan society into three tiers: Europeans at the top, Asians in the middle, and Africans at the bottom. This divide-and-rule approach allowed a tiny white minority to dominate the economy and politics, but it sowed seeds of resentment that would long outlast colonialism. Asians often found themselves in an awkward position – privileged relative to Africans in terms of economic opportunity, yet victims of racism and exclusion by the British. They were taxed heavily and yet denied equal political representation. (When Indians agitated for a bigger say in government, the colonial state grudgingly allocated a few legislative council seats in the 1920s – but simultaneously barred any African representation entirely) Africans, of course, bore the worst exploitation, including forced labor schemes (like the “hut tax” that compelled African men to seek low-paid work, often on European farms or in railways and ports). With the railway enabling swift movement of people and goods, the British could intensify their economic extraction – African-grown crops had to travel on freight cars just like everything else – while also swiftly deploying troops to quell any resistance. The very railroad built by Indian and African hands became an instrument to entrench colonial control. Under this system, Nairobi’s bustling Indian bazaars and the African markets operated in the shadows of grand European boulevards, each community wary of the other and kept apart by design. The British had effectively constructed not just a railway, but an ethnic and class fault line across the colony. It is a legacy of division that would manifest in various forms long after the last steam engine blew its whistle under the Union Jack.

Memory, Monuments, and Erasure

Today, the story of the Uganda Railway still looms large in East African history – yet the way it’s remembered is a patchwork of myth, nostalgia, and silence. Ask many Kenyans about the railway and you’ll get a few familiar anecdotes: the man-eating lions of Tsavo (1898), perhaps, or the time Teddy Roosevelt’s safari train rolled through, or broad claims about how the “iron snake” opened up the highlands and made Kenya possible. These tales – equal parts romanticized and horrific – tend to center on big, dramatic moments or colonial heroism. The true backbone of the railway’s story, the thousands of humble workers who sweated and died laying the tracks, often goes unmentioned. Their memory has largely been erased or overlooked in the public narrative. As one writer poignantly asked, where are the stories of “the men and women…who built and ran this railway… Are these stories not part of the railway, do they not deserve to be heard or remembered?”. It’s a glaring omission. There is no national holiday for the railway builders, no big-budget movie celebrating their saga (except when they feature as nameless extras getting eaten by lions!). Their graves lie mostly untended along the line, their names lost to time, save for a few mentions in colonial records.

That’s not to say there are no memorials at all. In the town of Makindu, roughly halfway between Mombasa and Nairobi, stands a remarkable monument to the railway workers – albeit in the form of a house of faith. The Makindu Sikh Temple (Gurdwara), a gleaming white structure, was built in 1926 by Sikh railway staff and former workers. Its origins go back to 1898, when Sikh laborers building the railway would gather under a lone tree at Makindu camp to pray and sing hymns after their grueling workdays. That humble tin-roofed makeshift shrine grew into a permanent temple, which still serves travelers today, offering free meals (langar) to all who pass through – just as those Sikh workers fed the hungry back in the dayen.. It is a living memorial, one of the few places in Kenya where the spirit of the coolie laborers is explicitly honored. Elsewhere, one finds scattered plaques or preserved relics. The Nairobi Railway Museum, established in 1971 near the old Nairobi Station, curates some of the physical legacy: steam locomotives, tools, photographs, and even the legendary carriage dubbed the “Hell’s Gate Coach” which was attacked by lions during construction. The museum stands as a repository of the railway’s history and, by extension, a tribute to those who built it – though the focus tends to be on the trains and tracks more than the people. Still, stepping into its galleries one can’t help but sense the ghosts of the past. “The museum is the living memory of the Uganda Railway… unraveling the very fabric of its colonial past,” writes one visitor, noting how it confronts the audacity and brutality of the railway’s story in equal measure.

However, outside such enclaves of memory, much of the railway builders’ legacy has faded. Post-independence Kenya, in forging a national narrative, emphasized African resistance and the fight against colonialism more than the nuances of how colonial infrastructure was built. The contribution of the Indian workers was politically awkward in some ways – they were part of a colonial project, yet also victims of it and later contributors to Kenyan society. Until recently, Kenyan school textbooks gave scant attention to the “Asians” in Kenya’s history. There were also periods of active erasure: for instance, in 1972 Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled tens of thousands of Asians from Uganda, effectively attempting to wipe away the Asian community’s presence (many of whom were descendants of railway workers who had settled in Uganda). In Kenya, no such wholesale expulsion occurred, but through the 1960s-70s many Asians emigrated under pressure (more on that shortly). All of this meant that for decades, the memory of the railway laborers lived on mainly within the Kenyan Asian community itself and in family stories. Only in recent years has there been a resurging interest – partly due to the 50th anniversary of the Ugandan Asian expulsion prompting reflection, and partly due to a new “Save the Railway” heritage project documenting the old railway before it was superseded by a new one. Indeed, the old “Lunatic Line” eventually ceased most operations by the 2000s, overtaken by highways and neglect. In 2017, Kenya inaugurated a shiny new Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) built by Chinese contractors, paralleling the old route from Mombasa to Nairobi. It’s been dubbed the “new Lunatic Express” by some wags, drawing comparisons to the old colonial venture (right down to debates about cost and benefit). The new project has, inadvertently, shone a light back on the old line – reminding Kenyans that a century ago, a similarly ambitious railway was built at great human cost. As trains now speed past in hours what once took the sweat of years to traverse, one hopes the country remembers who laid those original tracks, and that their story is not lost to the bushes reclaiming the disused rails.

Conclusion: Steel and Bloodline

In the end, the saga of the Indian labourers who built the Uganda Railway is a story of ironies as much as iron rails. What began as an imperial “steel dream” – a grand, costly gamble to cement British rule – became, over time, the backbone of an independent Kenya and the provenance of a diverse society. The steel of the railway has long since aged and rusted in places, but the bloodlines of those who built it continue to run through Kenya’s population. The descendants of the railway workers and other Indian migrants are today an integral part of the nation, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. In 2017, in a poignant recognition of this fact, the government of Kenya officially declared its Asian (Indian) community to be the 44th tribe of Kenya. It was a symbolic gesture, acknowledging that after more than a century, the people who once were viewed as transplant outsiders (or indeed, indentured “coolies”) are undeniably Kenyan. This moment of pride, however, belies the complicated path that led here – a path full of contradictions.

The railway built with blood and sweat did indeed help birth a modern nation, but not without pain. The contradiction of the Uganda Railway is that it was both a tool of oppression and a vehicle for liberation. It was constructed to facilitate colonial exploitation – yet those same tracks later carried the soldiers of the King’s African Rifles who fought fascism in World War II, and then, paradoxically, the detainees in the 1950s whom the colonial government tried to break during the Mau Mau rebellion. (The rebels called the train that transported prisoners “gari ya waya,” the wire-mesh wagon – a cruel misuse of a railroad originally sold as a gift to the land.) After independence in 1963, the railway’s role changed again: it became a national utility, and the once segregated first-class coaches were opened to all Kenyans. Yet the euphoria of independence brought its own contradictions for the Asian community. Despite their contributions, many Asians felt uncertain in the new Kenya. The African majority, having suffered under both British and Asian merchants (some of whom were seen as complicit in the colonial system), pressed for “Africanization” of the economy. Many Asians were compelled or encouraged to give up shops and jobs to African nationals. In the late 1960s, laws required non-citizen Asians to obtain work permits and restricted where they could trade. Thousands who had retained British passports opted to leave, moving to the UK or elsewhere. Kenya’s Asian population shrank dramatically – from about 180,000 on the eve of independence to barely 80,000 a decade later as families emigrated. Those who stayed often had to fight anew for acceptance and opportunity in the country they knew as home.

And yet, here is where the story comes full circle. The Kenya of today is a place where you can find a Patel Street in Nairobi, a Sikh gurdwara feeding travelers in Makindu, and a bustling “Little India” marketplace in Kisumu – all direct legacies of those railway builders. It’s a land where a Kenyan of Asian descent might serve in parliament or captain the national cricket team, even as debates about identity and belonging persist. The railway, that iron snake, bound together the coast and the interior; in doing so, it also bound together the fates of Indians, Africans, and Europeans in a way none of its British planners could have envisioned. It created a country, “helped create a nation,” as some say, but also left behind a tangle of social tracks that Kenya is still unwinding. The tale of the Uganda Railway’s construction is thus more than a chapter in engineering history – it’s a human epic of sweat, sacrifice, aspiration, and resilience. The very term “coolie,” once used to demean the Indian workers, has been transformed by the dignity of their legacy. With each generation, the descendants of those laborers have woven themselves more deeply into Kenya’s fabric, contributing in business, academia, arts, and public service.

Standing at Nairobi’s Railway Museum or gazing at the old iron rails being slowly consumed by rust and vines, one can almost hear the echoes of the past – the clink of hammers on spikes, the groan of straining men lifting timber, the roar of a lion in the night, the laughter and prayers in an Indian camp at dusk. It is the sound of blood, sweat, and steel forging something enduring. The Uganda Railway was built on the backs of ordinary men from distant lands, and it in turn built extraordinary destinies for the land it traversed. In Kenya’s diversity and in its ongoing struggles with the ghosts of colonialism, the imprint of that railway – and the laborers who made it possible – remains as indelible as ever. Steel and bloodline, empire and migration, oppression and opportunity – these dualities define the railway’s legacy. Over a century later, Kenya continues to ride the rails laid down by those “lunatics” and their loyal coolies, ever forward, hurtling into an uncertain future while carrying the weight of a remarkable past