In the hills and coastal forests of Kenya’s south lived a tradition that quietly embodied the spiritual and artistic genius of the Mijikenda people. Long before colonialism and tourism reduced African art to souvenirs, the Mijikenda carved figures of remembrance called vigango—wooden memorial posts that stood as spiritual intermediaries between the living and the dead. To outsiders, they appeared as abstract totems. To their makers, they were living symbols of ancestral presence, repositories of power, and evidence of a sacred continuity that bound community to cosmos.

When Jean Brown Sassoon published her study Traditional Sculpture in Kenya in 1972, she described a paradox. Despite Kenya’s diverse ethnic mosaic, few traditional sculptures had survived or been documented. Christian missionary activity, colonial disruption, and the transience of wood in humid climates had nearly erased centuries of material culture. Yet among the Mijikenda of the coastal hinterland, sculpture endured—not as ornament but as religion in wood (Sassoon, 1972).

Spirits in Wood: The Meaning of the Vigango

The Mijikenda, a group of nine closely related Bantu-speaking communities stretching from the Sabaki River to the Tanzanian border, practiced a spiritual system centered on the kaya—a fortified forest settlement regarded as both ancestral home and sacred shrine. Within these sacred groves, families and clans honored their dead elders through the erection of vigango (singular: kigango).

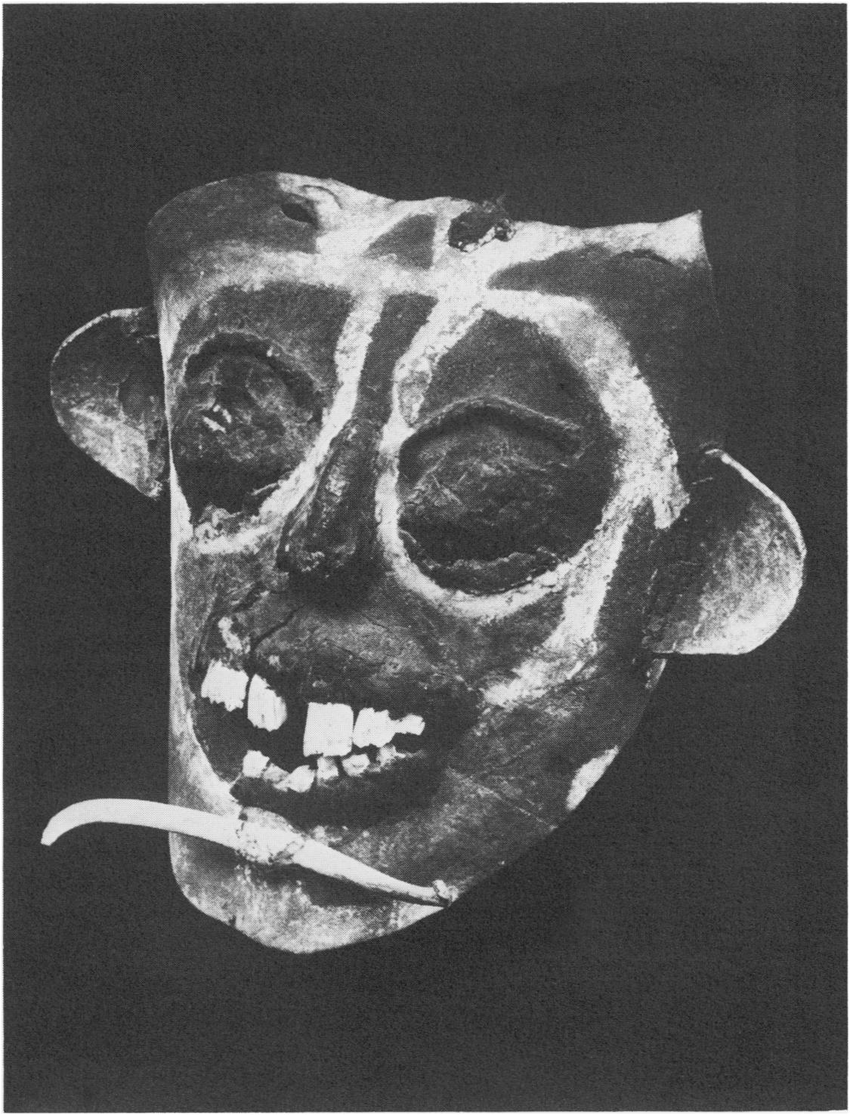

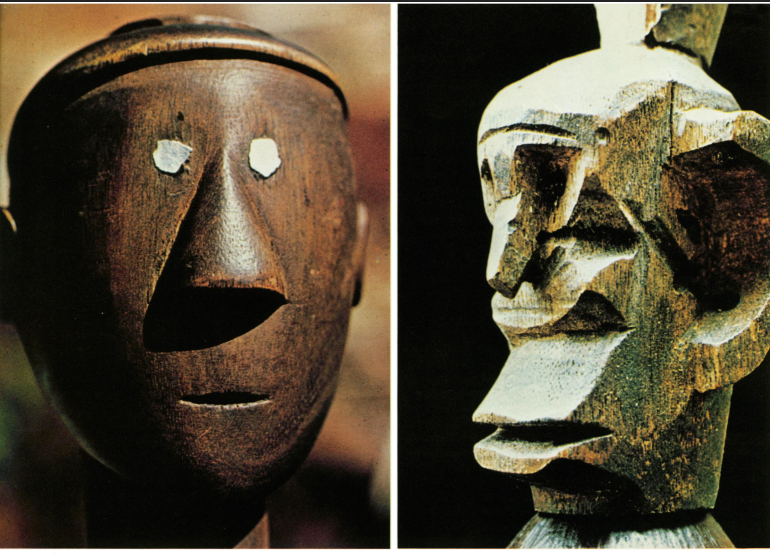

A kigango was not a likeness in the Western artistic sense. It was a stylized, upright wooden post, carved from hardwood such as mpingo or muhuhu, often standing between four and eight feet tall. Its geometric form—sometimes human-like, sometimes abstract—embodied the spirit of a deceased koma (ancestral elder and moral exemplar). Once consecrated, the figure served as a seat for the spirit’s presence and a guardian of the household.

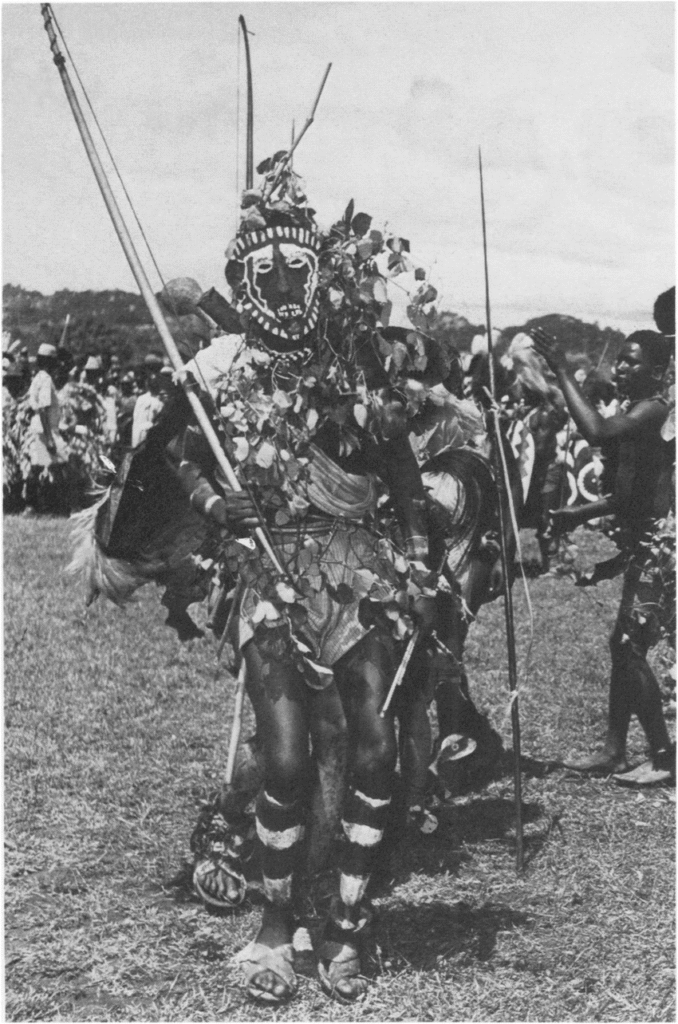

Sassoon (1972) noted that vigango were “not static memorials but active members of the community.” They received offerings of millet, palm wine, or blood during family rituals and were consulted for protection and blessing. In many Mijikenda dialects, the word kigango derives from the root -ganga, meaning to stand firm or to heal—a fitting metaphor for a spiritual pillar. The carving itself was an act of reverence and continuity: each figure was commissioned by the deceased’s family or secret society, typically the Gohu or Kambi ya Kifudu, which specialized in ritual and ancestral communication.

Art as Memory and Power

In precolonial Mijikenda life, art did not exist apart from religion. The making of a kigango was a sacred duty performed by initiated men, not for aesthetic display but for social and moral preservation. The figures represented ethical ideals—courage, generosity, and wisdom—and their presence in the homestead signaled ancestral approval.

The vigango were placed outside houses or within the family shrine, arranged in rows that traced lineage history. Over time, the weathering of the wood was not decay but transformation; as the figure darkened and eroded, it became spiritually mature. The same process reflected the Mijikenda idea of death—not an end but a deepening of existence.

Mbiti (1975) described such ancestral veneration as “the living-dead concept,” where the departed remained moral witnesses. The vigango thus embodied that principle physically. They connected the visible world to the invisible and reminded the living of their obligations to family, clan, and God (Mulungu). In this sense, Mijikenda sculpture was philosophy carved in wood—a theology of continuity expressed through form.

Colonial Disruption and the Art Market

The colonial encounter fractured this sacred equilibrium. Missionaries condemned vigango as pagan idols, while administrators banned certain rituals associated with ancestor worship. By the mid-twentieth century, the rise of Christianity and urban migration had already diminished carving traditions.

Sassoon’s fieldwork in the late 1960s revealed a more disturbing trend: sacred vigango were being stolen or sold to foreign collectors. Western museums and art dealers, fascinated by the geometric simplicity of the carvings, reclassified them as “tribal art.” Stripped of context, they were displayed in galleries alongside West African masks and statues, their spiritual function reduced to aesthetics.

The Kenyan government had few laws to protect traditional artifacts, and the Mijikenda themselves, often impoverished, were pressured or persuaded to sell. Anthropologist Monica Udvardy later documented how hundreds of vigango found their way into American university museums during the 1970s and 1980s, often through intermediaries who treated them as “ethnographic pieces.” What had been sacred mediators were now commodities (Udvardy, Giles, & Mitsanze, 2003).

Colonial anthropology further distorted their meaning. European scholars often classified the Mijikenda as “non-sculptural peoples” because their art was not figurative in the European sense. Sassoon (1972) challenged this assumption, emphasizing that abstraction was itself an aesthetic and spiritual choice. The minimalism of the kigango—its straight lines, subtle facial marks, and absence of ornament—expressed moral restraint and permanence. In other words, it was not the absence of art but the presence of philosophy.

The Vanishing Carvers

By the 1970s, few Mijikenda artisans continued to carve vigango for religious use. The younger generation, educated in mission schools, regarded the tradition as backward or dangerous. Some carvers shifted to producing “tourist sculptures” in Malindi and Mombasa—miniature versions of vigango stripped of their ritual essence. Sassoon observed that these commercial copies, often made from softwood and artificially darkened, bore little spiritual resemblance to the originals.

Traditional carvers operated within moral codes that forbade selling a kigango outside the family or community. Each figure was part of a relational network—its removal from the shrine was considered a rupture in ancestral order. Yet, with the rise of tourism and urban art markets, carving became detached from ritual. The sculptor’s role changed from mediator to merchant, signaling a broader cultural transformation under modernity.

The loss of traditional sculpture reflected a deeper spiritual loss. As Mbiti (1975) noted, African art was “a theology in material form,” inseparable from faith. When art became divorced from ritual, the moral language of the community weakened.

Return and Recognition

In the early twenty-first century, awareness of this cultural theft sparked global conversations about repatriation. The National Museums of Kenya, in collaboration with scholars such as Monica Udvardy and Linda Giles, identified more than 400 vigango in U.S. and European collections. Some institutions—most notably the Illinois State Museum and the Fowler Museum at UCLA—have since repatriated a number of figures to Kenya, where they are stored for eventual return to Mijikenda communities.

Repatriation, however, raises complex questions. Many elders argue that sacred objects lose their spiritual power once displaced. Without the proper rituals of reinstallation, returning them is like bringing home an empty shell. Others see repatriation as moral restitution—a recognition that ancestral memory cannot be owned. Either way, the vigango have forced Kenya and the world to confront how colonialism commodified not just bodies and land, but belief itself.

Modern Kenyan artists, too, have re-engaged with the legacy of the vigango. Sculptors such as Elkana Ong’esa and Francis Nnaggenda have drawn inspiration from traditional forms to express continuity between the sacred and the modern. In their work, the vertical rhythm and spiritual gravity of the old carvings find new life in stone and bronze.

Legacy

The story of the vigango reveals more than the loss of a single art form—it tells of the resilience of a worldview. Though the physical figures may vanish, their moral meaning endures in the collective memory of the Mijikenda and the broader Kenyan cultural landscape. They remind us that art, in African contexts, was never mere decoration; it was the visible breath of the unseen, the moral architecture of community.

Sassoon (1972) concluded that traditional sculpture in Kenya was “not extinct but hidden, preserved in the consciousness of its people.” Half a century later, her observation remains true. The sacred forests of the coast, where vigango once stood, still echo with rituals of remembrance. New forms of Kenyan art continue to draw from this lineage, proving that spirituality cannot be colonized.

The vigango stand, even in absence, as eloquent witnesses to a moral universe where art and belief are one. Their story is Kenya’s story—a dialogue between the living and the dead, between creation and continuity.

References

Mbiti, J. S. (1975). Introduction to African religion. London: Heinemann.

Sassoon, J. B. (1972). Traditional sculpture in Kenya. African Arts, 6(1), 16–21, 58, 88.

Udvardy, M. D., Giles, L. M., & Mitsanze, J. (2003). The return of the vigango: A case study of Kenyan sacred art repatriation. Nairobi: National Museums of Kenya.