Kenya’s independence is usually remembered in color. The Union Jack came down in December 1963, flags waved in Uhuru Park, Jomo Kenyatta declared freedom at last. What rarely makes it into the story is that even as Nairobi was celebrating, another Kenya was already at war. In the dry, endless lands of the Northern Frontier District, the guns never went silent.

Independence and a War Nobody Talks About

This was the Shifta War, Kenya’s first internal war, fought from 1963 to 1968. It was not called a war at the time — Nairobi preferred the word “Shifta,” Somali for “bandit,” to make it sound like nothing more than cattle thieves. But the reality was an armed insurgency for self-determination. For the Somali communities of the North, independence did not mean freedom under Nairobi; it meant being folded into a country they had not chosen.

The war shaped Kenya’s borders, its politics, and its legacy of violence against its own citizens. Yet, unlike Mau Mau, it sits in silence, tucked away as a footnote. Ask most Kenyans today and they will tell you “Shifta” means criminal, not insurgent. That erasure was deliberate.

The Northern Frontier and Its Discontents

The Northern Frontier District (NFD) was never central to the British colonial project. It was vast, dry, sparsely populated, and expensive to administer. To the British, it was a buffer zone against Ethiopia and Somalia. To the Somali people who lived there, it was home, linked by kinship and trade to the Somali Republic across the border.

As independence approached, the question of what to do with the NFD became a crisis. Britain set up the Robertson Commission in 1962 to ask the people themselves. The answer was overwhelming: most wanted to secede and join Somalia. It was the most democratic moment in the story — and also the most ignored. The British, worried about angering Ethiopia and keeping their new client state Kenya stable, handed the NFD to Nairobi anyway.

The result was betrayal at the very birth of Kenya. Somali leaders felt independence had not freed them, only changed the flag flying over them. Within months of 1963, armed groups had formed, supported by the Somali Republic. What Nairobi called “banditry” was in fact secessionism: a demand that the NFD’s Somali population be allowed to decide its own destiny.

The new Kenyan government’s answer was not negotiation, but war.

The Outbreak of War

Kenya was barely a few weeks old when it declared war on part of itself. In the Northern Frontier District, secessionist groups had begun to organize even before the Union Jack was lowered. To them, independence was meaningless if it meant trading British administrators for Kikuyu and Kamba elites in Nairobi. The 1962 Robertson Commission had confirmed their position — almost every Somali respondent wanted to join the Somali Republic. But London and Nairobi dismissed the results.

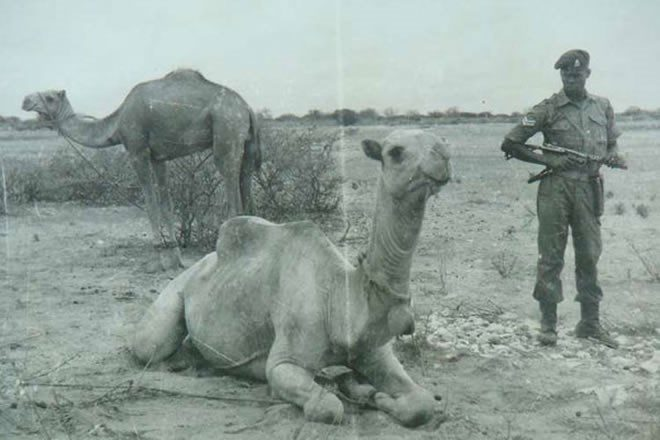

By early 1964, armed insurgents were launching raids on police posts, ambushing convoys, and declaring their loyalty to Mogadishu. They were not a large, organized army, but they knew the terrain — the endless scrublands, dry riverbeds, and thorny plains that made pursuit nearly impossible. They had allies across the border in Somalia, who supplied them with weapons, safe havens, and propaganda. In Nairobi, the new Kenyatta government gave them a name: Shifta.

It was a clever move. The word “shifta” in Somali literally means “bandit,” but in state propaganda it stripped the insurgents of any political legitimacy. They were no longer fighters for self-determination; they were criminals. Every raid on a police post became cattle theft, every ambush of a convoy framed as lawlessness. By naming them bandits, Nairobi made the war a police problem instead of a political one.

But behind the label was a serious secessionist struggle. The Shifta had a vision, however messy: to merge the Northern Frontier District with Somalia, creating a “Greater Somalia” that stretched from the Horn into northern Kenya. Mogadishu broadcast radio programs encouraging the fighters, portraying Kenya as an illegitimate colonial creation. Across the border, Somali officials promised to keep supporting the insurgents until their dream of unification was achieved.

Nairobi responded by flooding the frontier with police and the army. Roadblocks sprang up, and entire districts were put under emergency regulations. What had begun as a demand for self-determination was now a full insurgency, and Kenya’s brand-new statehood was already bleeding at the edges.

Counterinsurgency — Kenya’s Iron Fist

The Kenyatta government did not treat the Shifta War as a political problem. It treated it as a disease to be cut out, and the scalpel was the state’s full coercive power. The blueprint was not new — it looked eerily like the counterinsurgency campaigns the British had run just a decade earlier during Mau Mau. Only this time, it was an African government using colonial methods on its own citizens.

The strategy was brutal and simple: break the connection between the insurgents and the people. The government declared emergency regulations across the Northern Frontier District. Freedom of movement was revoked. Entire communities were ordered to move into “protected villages” — in reality, makeshift camps where people were corralled under military watch. These were meant to isolate civilians from the Shifta, but they were little more than open-air prisons. Food was scarce, disease spread easily, and communities that had once been pastoral and mobile were suddenly trapped and starving.

Cattle, the lifeblood of Somali pastoralists, became another weapon of war. Security forces carried out mass confiscations, seizing herds under the pretext of cutting off Shifta supplies. Thousands of animals were driven away, sold, or simply shot. To destroy the insurgents, the government destroyed the economy of an entire people.

Villages suspected of harboring Shifta were burned. Collective punishment became the norm: if one fighter struck from an area, the whole community paid. Stories filtered back of elders executed as examples, women beaten, children going hungry behind barbed wire. Nairobi insisted it was necessary — that only harsh measures could bring “order” to the frontier.

By 1965, the NFD had become a militarized zone. Checkpoints, patrols, and curfews ruled daily life. Civilians lived under constant suspicion, treated less as citizens and more as enemies within. The government’s own language betrayed its approach: not Kenyans, but “Shifta sympathizers.” In practice, there was little difference.

The cost was staggering. Estimates vary, but thousands of Somali civilians died, either in direct violence or from starvation and disease inside the villagization camps. Livestock losses crippled the region for generations. What began as a political dispute over self-determination became a humanitarian disaster authored by the state itself.

And yet, even with all this brutality, the Shifta insurgency did not collapse immediately. Fighters still raided, still ambushed convoys, still slipped across the Somali border. Kenya had the stronger army, but the frontier was vast and porous. The war dragged on, a low-intensity conflict that bled the young nation and revealed the fragility of its independence.

International Dimensions

The Shifta War was not only a local insurgency; it was part of a larger regional and global game. At its heart was the idea of “Greater Somalia” — a dream of uniting all Somali-inhabited territories into one state. When Somalia gained independence in 1960, it immediately laid claim to the Somali-populated parts of Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Kenya’s Northern Frontier. Kenya’s independence, instead of closing the colonial map, had only inflamed it.

Somalia threw its weight behind the insurgents. Arms, training, and propaganda crossed the porous border. Radio Mogadishu broadcast fiery messages in Somali, urging fighters to resist Kenyan rule and painting Nairobi as just another colonial master. In Nairobi, officials saw not just cattle rustlers but a proxy war for the soul of the frontier.

Ethiopia, itself facing Somali irredentism in its Ogaden region, quickly sided with Kenya. In 1964, the two countries signed defense agreements and began sharing intelligence. What might have remained a domestic insurgency was now shaping Kenya’s foreign policy.

The Cold War added another layer. Somalia leaned towards the Soviet Union, while Kenya and Ethiopia secured support from the West. Britain, the former colonial master, supplied Kenya with military equipment and training. Israel, worried about the Horn of Africa falling under Soviet influence, quietly provided assistance too. In Nairobi, Kenyatta’s government presented the Shifta War as not just a security crisis but a frontline in the fight against communism. It worked — foreign allies sent aid, advisors, and weapons.

This international framing helped Nairobi mask the brutality of its counterinsurgency. To outsiders, Kenya was a responsible state defending its territorial integrity. To those living in the Northern Frontier, it was occupation by another name. The irony was hard to miss: Kenya, fresh from escaping colonial rule, was now invoking colonial borders and Cold War alliances to crush a people who wanted the same freedom.

By the mid-1960s, the war was no longer just about Kenya and its Somali citizens. It had become a node in the wider struggle between pan-Somali nationalism, regional stability, and Cold War geopolitics. And in that triangle, it was the people of the frontier who paid the heaviest price.

The End of the War

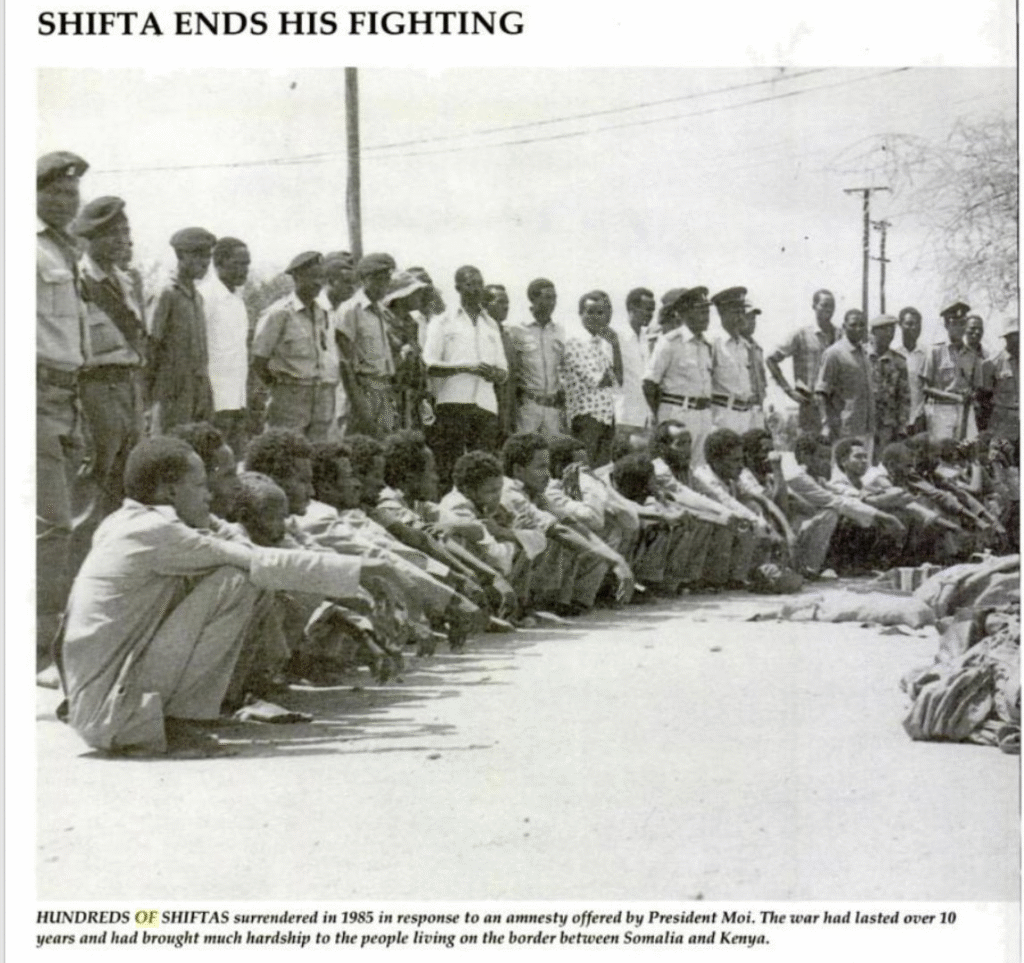

By 1967, the Shifta insurgency was running out of steam. Years of forced villagization, cattle confiscation, and food blockades had devastated civilian support. Communities that had once sheltered fighters were now exhausted, starved, and broken. The guerrillas still moved across the scrub and slipped over the Somali border, but their ability to sustain large-scale operations was dwindling.

Somalia, once their most vocal backer, was also recalculating. The cost of supporting insurgents across three borders — Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti — was proving unsustainable. In 1967, a new Somali government came to power under Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, which signaled a willingness to de-escalate. The dream of Greater Somalia remained, but for the moment, Mogadishu sought diplomacy.

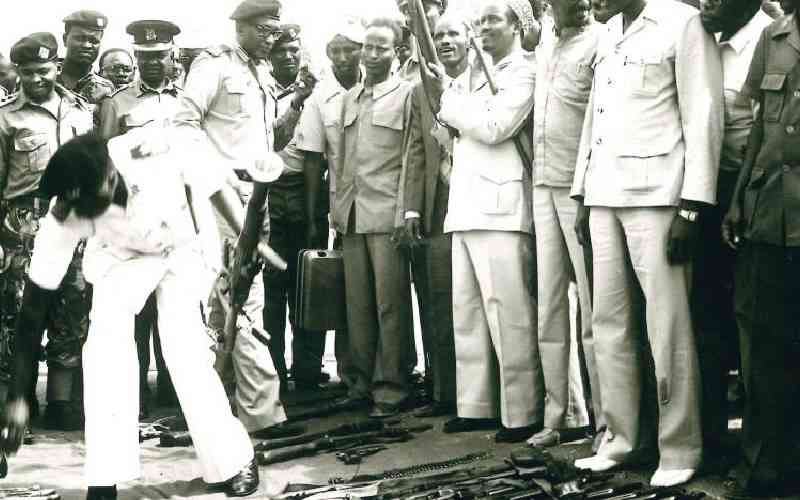

The turning point came with the Arusha Memorandum of 1967, brokered by Ethiopian mediation. Somalia agreed to stop arming and supporting the insurgents, while Kenya pledged amnesty to fighters who surrendered. The following year, Nairobi declared the war over. Officially, Kenya had survived its first internal conflict.

But victory came at a staggering price. The government never released exact casualty figures, but estimates suggest thousands of civilians were killed, and tens of thousands displaced into villages where disease and hunger took their toll. The livestock economy of the Northern Frontier was shattered, leaving scars that still shape the region’s poverty today.

For Nairobi, the war was a test of sovereignty — and a warning to any other group dreaming of secession. For the Somali communities of Kenya, it was the beginning of decades of marginalization, securitization, and mistrust. The word “Shifta” lingered not just as the name of a war but as a permanent label of suspicion, criminalizing entire populations.

When the guns fell silent in 1968, there were no celebrations, no parades. In the frontier, there was only silence, the kind that follows devastation. Kenya had held onto its borders, but it had lost something else: the trust of its own citizens in the North.

Legacy of the Shifta War

The Shifta War ended on paper in 1968, but in reality it never really ended. What Nairobi declared as victory was, for the people of the Northern Frontier, the beginning of a new political identity: that of a citizen always under suspicion. The war left scars not just in graves and burned villages, but in how the state saw its Somali population — as a security problem first, as Kenyans second.

The label “Shifta” became more than the name of an insurgency. It became shorthand for banditry, lawlessness, and treachery. Long after the last insurgents had surrendered, the word was casually applied to anyone in the region. It criminalized an entire community, erasing the fact that their demand for self-determination had once been recognized by the Robertson Commission. The political argument was forgotten; only the stigma remained.

The tactics of the Shifta War also set a dangerous precedent. Forced villagization, collective punishment, mass livestock confiscations — all were methods borrowed directly from the British counterinsurgency playbook. They would be repeated in later decades whenever Nairobi faced resistance at the margins. In 1984, the Wagalla Massacre in Wajir followed the same logic: cordon the people, punish them collectively, and call it security. In the 2010s, counterterrorism operations in Garissa and Mandera used food blockades and livestock destruction with an eerie familiarity. The Shifta War was Kenya’s template for governing dissent in its peripheries.

It also deepened the economic and political marginalization of the North. Before the war, the region was poor and neglected; after the war, it was devastated. Schools, roads, and hospitals remained scarce. Development was sacrificed for militarization. For decades, the Northern Frontier was ruled less by civil institutions than by provincial commissioners, military detachments, and emergency regulations. Independence had promised inclusion; instead, the North got occupation in another name.

Yet the memory of the war never disappeared. In Somali households, stories of the 1960s lived on: of families starved in “protected villages,” of herds confiscated, of elders humiliated. That memory fuelled distrust of Nairobi, and shaped politics for generations. Even in the 21st century, when leaders from the region speak of historical injustices, they are reaching back to the Shifta War.

Kenya’s official histories may have chosen silence, but the North remembers. And until that silence is broken, the war will remain unfinished.