Independence was supposed to end the shootings. The Union Jack had come down in 1963, and Kenyans were told they were free. But on October 25, 1969, in the lakeside city of Kisumu, it was Kenyan police and the presidential guard who opened fire on unarmed citizens. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of men, women, and children were cut down in broad daylight. The gun smoke did not carry the smell of empire this time — it carried the scent of betrayal.

Freedom at Gunpoint

The massacre was not a colonial relic. It was homegrown, the product of political rivalry, ethnic suspicion, and the authoritarian instincts of a young state. It revealed how quickly independence had turned into a monopoly of power, guarded not by persuasion but by bullets. Kisumu 1969 was not an accident; it was a message.

The Road to Kisumu

The seeds of the tragedy were sown three months earlier in Nairobi. On July 5, 1969, Tom Mboya — cabinet minister, trade unionist, and one of Kenya’s brightest political stars — was gunned down on Government Road (today Moi Avenue). His death shook the country, but in Nyanza, it confirmed suspicions that the Kenyatta government saw Luo political ambition as a threat.

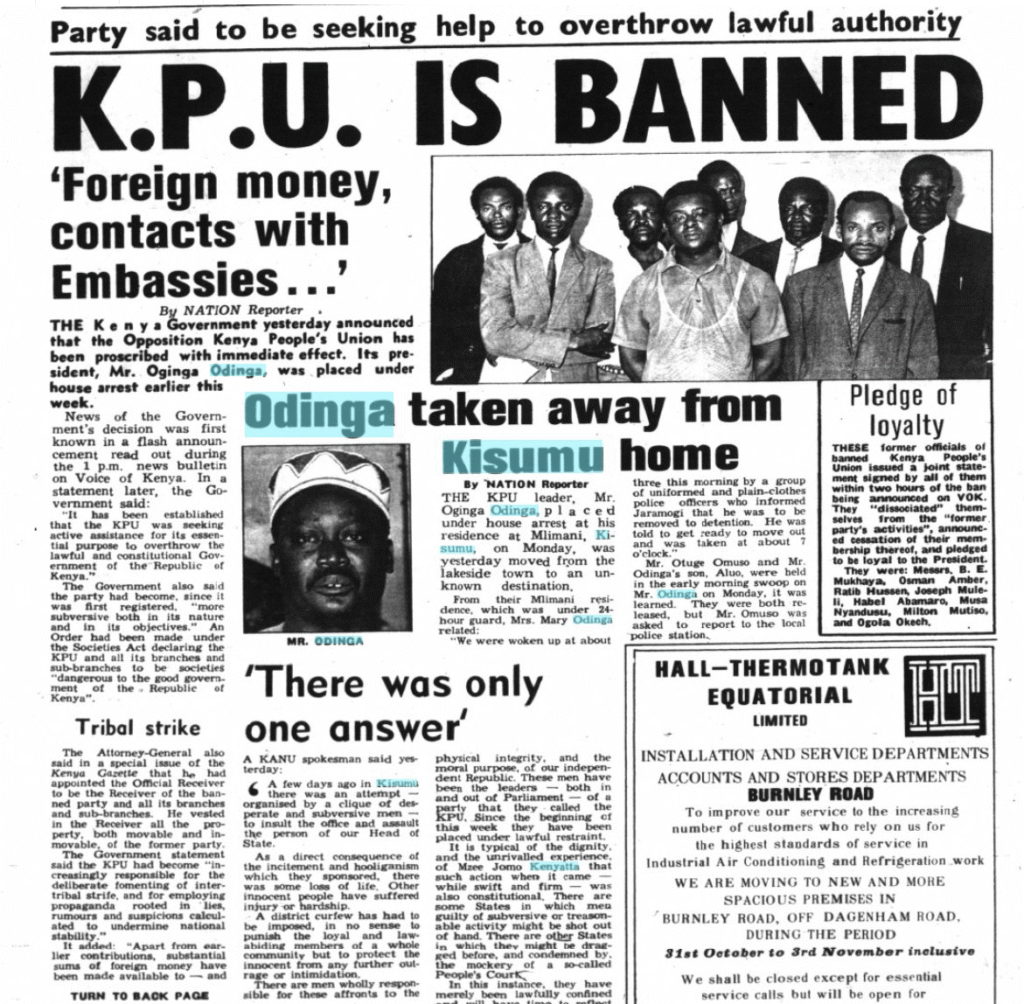

The Luo community had already been uneasy with the direction of independence. Oginga Odinga, once Kenyatta’s deputy, had broken ranks, accusing the ruling elite of abandoning socialism for land-grabbing and tribal patronage. He had formed the opposition Kenya People’s Union (KPU), headquartered in Kisumu, and had become a lightning rod for discontent.

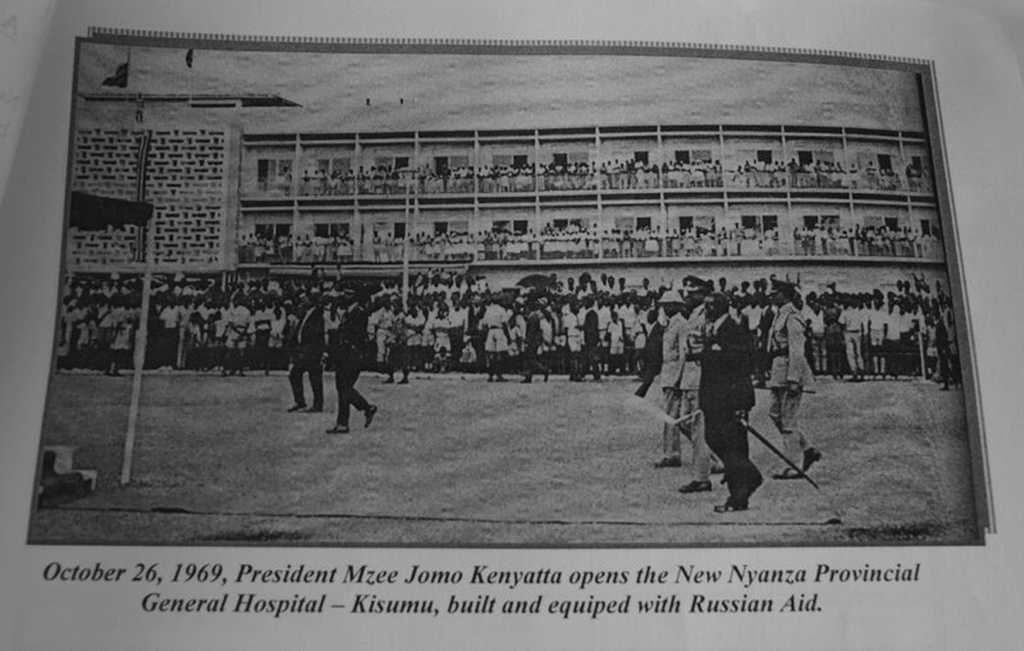

Mboya’s assassination poured fuel on the fire. In Luo Nyanza, grief turned into anger. Rumors swirled that the state itself had orchestrated his killing. When Kenyatta announced he would personally visit Kisumu in October to open the new Russia Hospital (built with Soviet aid), many saw it as provocation — the old man walking into the heart of opposition territory.

The stage was set: a city grieving a fallen son, a president facing hostility, and security forces primed to respond with force at the first sign of dissent. Kisumu was about to learn that in post-independence Kenya, asking the wrong questions could be fatal.

The Day of the Massacre

October 25, 1969. Kisumu was tense even before Kenyatta’s motorcade rolled in. The city’s air was thick with grief and suspicion. People still whispered Tom Mboya’s name in mourning, and his face lingered on posters and in memory. His assassination had not healed; it had festered.

The president had come to open the brand-new Russia Hospital — a gift from the Soviet Union, intended as a monument to modern medicine and diplomacy. But the choice of Kisumu was symbolic. This was Oginga Odinga’s stronghold, the headquarters of the Kenya People’s Union (KPU), and the epicenter of Luo political frustration. The visit was less about health care than it was about power: a reminder that even in the land of his rivals, Kenyatta was still head of state.

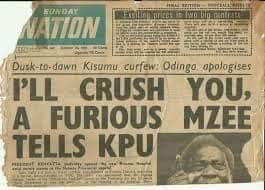

Crowds gathered outside the hospital grounds, lining the streets, but their mood was not welcoming. Instead of cheers, there were jeers. Some shouted about Mboya’s murder, others about Odinga’s treatment at the hands of the government. As Kenyatta stepped up to speak, hecklers cut through the ceremony. The old man lost his temper. Accounts differ, but what is clear is that the atmosphere snapped. Insults were traded between the crowd and the presidential entourage.

Then came the gunfire.

The presidential guard and police opened fire directly into the mass of civilians. Panic tore through the crowd as people scattered, some dropping instantly, others trampled in the chaos. Mothers carrying children fell. Young men who had come to shout slogans collapsed in pools of blood. Within minutes, Kisumu’s streets were strewn with bodies.

The official death toll was never clear. Government figures spoke vaguely of “a few deaths.” Witnesses spoke of dozens, some estimates stretching into the hundreds. The truth lay buried in hurried funerals and unmarked graves. For many families in Kisumu, loved ones simply vanished that day — swallowed by bullets and silence.

When the gunfire ceased, Kenyatta’s motorcade sped away. The Russia Hospital stood inaugurated, but the event was forever remembered not for healing, but for bloodshed. Kisumu had become the stage where independence revealed its darkest betrayal: a government turning its guns on its own citizens.

The Aftermath

The massacre did not end with the last bullet. It continued in the silence that followed, the silence of a government determined to erase its own crime. Hours after the shootings, Kenyatta’s administration moved swiftly to recast the narrative. Official statements spoke of a “riot,” of an unruly crowd that had forced security forces to act. The dead were reduced to statistics, the wounded to rumor.

But Kisumu remembered. Families mourned in whispers, burying their loved ones in haste, some in unmarked graves. The fear was palpable. To grieve too openly, or to question too loudly, was to invite the same guns.

Politically, the consequences were immediate and devastating. Within days, the government banned the Kenya People’s Union (KPU), the only significant opposition party. Oginga Odinga, already a thorn in Kenyatta’s side, was placed under house arrest. With KPU gone, Kenya became a de facto one-party state, where dissent was no longer debated but crushed.

Kisumu itself was left traumatized. Security forces patrolled the city, and residents lived under intimidation. The massacre carved a deep scar in Luo collective memory, reinforcing the belief that Nairobi’s state was not theirs, that independence had delivered not inclusion but exclusion by gunfire.

Nationally, the incident was buried. School textbooks skipped it. Newspapers that reported it toned down the language or risked censorship. The massacre became one of those events Kenya preferred not to remember, a ghost haunting independence narratives that only spoke of triumph and unity.

Yet the wound never healed. In Luo Nyanza, October 1969 became shorthand for betrayal — proof that the government would not hesitate to kill its own citizens in defense of power. The cries of the dead lived on in political songs, in whispered family histories, and in the unspoken distance between Kisumu and Nairobi.

Why Kisumu 1969 Matters

The Kisumu massacre is not just a footnote of post-independence politics. It is a mirror of Kenya’s darker truth: that the methods of colonial repression survived long after the colonizers had left. The rifles that cracked in Kisumu were not foreign anymore. They were in the hands of a government sworn to protect its people, turned instead against them.

Kisumu 1969 matters because it shattered the illusion of freedom. Six years into independence, Kenyans discovered that the new state was not above the tactics of empire — censorship, banning of opposition, and bullets for dissenters. What the British had done in places like Hola and during Mau Mau, Kenyatta’s government did in Kisumu. Independence had changed the flag, but not the logic of power.

It also matters because it deepened ethnic and political divides that still shape Kenya. The Luo community’s distrust of central government, often painted as tribalism, was forged in blood on that day. Mboya’s assassination, followed by the massacre, convinced many that the state was not neutral but hostile. Every subsequent election, every clash between Nyanza and Nairobi, carries echoes of 1969.

Finally, Kisumu matters because it fits into a longer pattern of state violence in Kenya. Hola in 1959, Kisumu in 1969, Wagalla in 1984, the Nyayo torture chambers of the 1980s, and the post-election violence of 2007–08 — all part of the same lineage. The state, when challenged, has often reached for the gun before dialogue. Kisumu was not the first time, and it would not be the last.

Remembering Kisumu is not about reopening old wounds; it is about acknowledging that the promise of independence was compromised early. Until the massacre is placed in its rightful place in Kenya’s national history, independence will remain a half-told story — one that celebrates freedom while ignoring the blood spilled to suppress it

Conclusion: The Blood Stain on Uhuru

The Kisumu massacre is the blood stain on Kenya’s Uhuru flag, the part of independence that official history has tried to scrub out. Six years after freedom, the state turned its rifles on its own people, and then pretended nothing had happened. For the families who buried their dead in haste, for the Luo community that carried grief into politics, Kisumu was proof that independence had been betrayed.

Kenyatta’s government silenced the gunfire but never the memory. In the official narrative, Kisumu was a “riot.” In lived memory, it was a massacre. The difference between the two is the difference between a state trying to protect itself and a state exposing its true face: authoritarian, intolerant, and willing to kill for silence.

Kisumu 1969 did not end that day. Its echoes live on in every confrontation between the Kenyan state and dissenting citizens, in every protest dispersed by bullets, in every massacre the government has preferred to deny rather than atone for. It was the moment independence showed it could reproduce the violence of colonialism — this time with an African finger on the trigger.

Kisumu remains the reminder that freedom is not just about flags and anthems. It is about whether a state can accept opposition without resorting to bloodshed. In 1969, the answer was written in corpses on Kisumu’s streets. And until that history is acknowledged, independence will always carry a shadow — the shadow of October 25, when Kenya betrayed itself.

Suggested Next Reads

- The Hola Massacre: When British Colonial Brutality Was Laid Bare

— Shows how colonial violence foreshadowed state brutality in Kisumu, making the massacre part of a long continuum. - The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy

— Traces the fight for opposition politics from Odinga’s KPU to the multiparty struggles of the 1990s. - 30 Images from Kenya’s 1982 Failed Coup

— Another moment when the state turned violent to protect itself, echoing the authoritarian response in Kisumu. - Why Are Kenya’s Youth Protesting? Understanding the Roots of Change

— A modern parallel: dissent in the streets met by police violence, tying today’s struggles to the legacy of 1969. - The Hit Squad: Kenya’s Golden Era of Boxing

— A softer interlink, but tied by Tom Mboya’s role in promoting sports as part of Kenya’s nation-building before his assassination.