Recruitment of Kenyan Soldiers for World War II

When World War II broke out, the British colony of Kenya became a vital recruiting ground for the British Army in Africa. During the war, about 98,240 Kenyans were enlisted as askaris (soldiers) in the King’s African Rifles (KAR), making up roughly 30% of that multi-colony regiment’s total strength. Most were volunteers, though colonial authorities often leaned on local chiefs to “encourage or persuade, even order” young men to join the war effort. Recruiters traveled to villages across Kenya, tapping into traditional warrior cultures and loyalty to the British King. Many chiefs and elders cooperated, and thousands of Kenyans came forward to serve “King Georgie,” as they called King George VI.

Motivations for enlistment varied. Some educated Kenyan men saw the army as a promising career or adventure, especially if other prospects were limited. For many rural recruits, the army’s steady pay and “promise of regular meals” were powerful incentives during hard times. The British also ran propaganda drives – even circulating shocking quotes from Hitler’s Mein Kampf about Africans – to rally black Kenyans against the Axis. Others felt a personal loyalty to the distant monarch; officers noted a genuine reverence for “King Georgi” among askaris in East Africa. Whether drawn by duty, wages, or coercion, tens of thousands of Kenyans entered military training in the early 1940s.

Training and Deployment to Burma

New Kenyan recruits underwent initial training in Kenya alongside fellow East Africans from Uganda, Tanganyika (Tanzania), and Nyasaland (Malawi). A huge Base Details Camp on the outskirts of Nairobi became the hub of East Africa Command’s wartime expansion. There, British and Commonwealth officers trained the newly raised battalions of the King’s African Rifles, turning farmers and herders from various tribes into disciplined infantry. By 1943, Britain had decided to deploy a full East African force to the distant Burmese front against Japan – an unprecedented step of sending African soldiers to fight in Asia.

Kenyan units were organized mainly under the 11th (East Africa) Division, formed in 1943 and composed of troops from Kenya and neighboring colonies. One of its infantry battalions was the 11th (Kenya) Battalion, KAR, making Kenyan askaris a core part of the division. In June 1943, after months of drilling in East Africa, the division embarked on its journey to the Far East. As one British officer recorded, “in convoy we covered some 300 miles of Kenya to Mombasa and embarked on two ships. Our immediate destination was Ceylon. The sole purpose…was jungle training”. Indeed, the 11th Division was shipped to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) for intensive training in jungle warfare, since the rainforests of Burma would be unlike anything in Africa.

By early 1944, the Kenyans and their East African comrades had finished training in Ceylon and India, and they joined the British Fourteenth Army in the Burma Campaign. Kenya’s soldiers were now part of what would be called the “Forgotten Army” – the multinational Allied force fighting a grueling campaign in Burma’s remote jungles. Kenyan askaris landed in India and then moved up to the front in Assam, on the India-Burma border, by mid-1944. For many, it was their first time outside Africa. They had endured a six-week sea voyage and further drills in foreign lands; now they were about to face the Japanese in battle.

Combat and Contributions in the Burmese Jungle

Kenyan soldiers found themselves in a harsh new environment when they entered Burma. The East African troops were given an important role in late 1944: the 11th (East Africa) Division took over the spearhead of the Allied offensive in the mountainous frontier region of northwest Burma. Their task was to advance through the thickly forested Kabaw Valley, capture the Japanese-held villages of Kalemyo and Kalewa, and secure crossings over the Chindwin River. This valley, as one KAR veteran recalled, was “infested with malaria and scrub typhus…a depression of dense teak forest drenched with unceasing downpours of torrential rain”. The Kenyan askaris thus faced not only a determined enemy but also mud, monsoon rains, and disease in the jungle-covered hills.

Despite the extreme conditions, Kenyan troops quickly proved their effectiveness in Burma’s jungles. Their prior experience in “bush warfare” in Africa and their hardiness helped them adapt to Burmese terrain. British officers observed that East African soldiers often showed an uncanny ability to detect the enemy in the foliage – a “sixth sense in the bush” that sometimes outstripped their British superiors’ awareness. In fact, African askaris gained a fearful reputation among Japanese troops. Japanese rumors falsely accused the African soldiers of cannibalism, playing on racist tropes; ironically, this myth worked in the Allies’ favor, as some Japanese feared that being killed by a black African meant they would not reach their afterlife. While completely untrue, such stories sapped Japanese morale.

Throughout late 1944, Kenyan infantrymen slogged forward under monsoon rains, often waist-deep in mud. They learned to improvise and endure: building log bridges, hacking paths through thick bamboo, and hauling supplies on their backs where even pack mules failed. In one noted example of engineering work, East African soldiers skillfully “corduroyed” miles of muddy track with felled timber to enable their division’s vehicles to advance during heavy rains. Such efforts were crucial in keeping the Allied advance moving when weather grounded air support and bogged down transport. British commanders later praised the African divisions as “some of the best jungle fighters among the Allies”, able to press on in terrain and monsoon conditions that would halt many others.

The Kenyans saw intense combat as they pressed the Japanese rear guard. In October 1944, during a major push down the Kabaw Valley, the 11th East African Division’s 26th Brigade (which included Kenyan troops) fought a tough battle to take a Japanese hill position. The fighting was fierce and personal. A number of Kenyan askaris fell, including several NCOs; one brigade attack cost the lives of a company sergeant-major, an officer, and 11 askaris before the Japanese defenses were overcome. Japanese diaries recovered later paid grudging respect to the African soldiers’ courage. One Japanese entry noted of West African troops (in a parallel campaign) that “they are not afraid to die… even if their comrades have fallen, they keep on advancing as if nothing had happened. They have an excellent physique and are very brave”. The same could be said of the Kenyans in Burma – their resolve in battle made a strong impression on friend and foe alike.

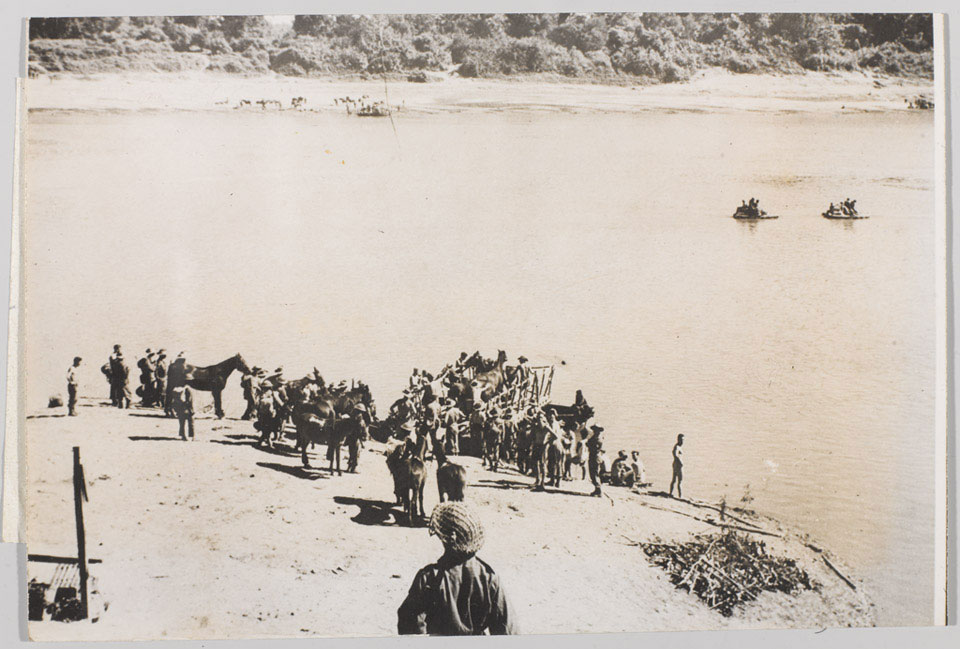

By December 1944, the 11th (East Africa) Division – with Kenyans in its ranks – had achieved its objectives. They fought their way to Kalewa on the Chindwin River by 2 December 1944. Soon after, East African engineers threw pontoon bridges across the broad Chindwin. This feat allowed Allied forces to establish a firm bridgehead for the next stage of the Burma campaign. Indeed, a British correspondent marveled that the march of the 11th East African Division “through the mud and the rain of [the] monsoon” to the Chindwin was an “achievement of the impossible”. Their advance helped force the Japanese to abandon their last positions on the India–Burma border – what one report called the “gateway to Mandalay” – opening the path for Allied armor and reinforcements. In early January 1945, having fulfilled their mission, the exhausted East African Division was pulled back to India for rest and refitting. Some elements (including independent Kenyan-led units) later rejoined the final Allied drive in 1945, but the bulk of Kenya’s soldiers had seen their major combat tour conclude after roughly six months of frontline action in Burma.

Throughout the campaign, Kenyan askaris endured tremendous hardships. One Kenyan veteran, Eusebio Mbiuki (who had enlisted in 1940 at age 22), later described how brutal the conditions were: “Rations were in short supply while rain was often torrential and the forests filled with tropical disease. Most of the time you’d want to run away,” he remembered. “But you would just say, ‘God help me. God help me. One day I’ll go home.’” His words capture the mixture of fear and determination that sustained many Kenyan soldiers. They faced relentless monsoon rains, mud, leeches, oppressive heat, and the ever-present threat of malaria, dysentery, and other illnesses. In fact, disease would claim far more African soldiers than enemy bullets. Medical records show some units in Burma evacuated seven men sick for every one wounded in combat – a testament to how sickness was the greatest enemy in the jungle. Yet, despite these challenges, the Kenyans proved resilient. They adapted their diets (learning to eat unfamiliar tinned rations or Indian curries), and even picked up new habits like smoking or reading newspapers during downtime in camp. Many also found camaraderie with soldiers from India, Britain, and other colonies, forging bonds in the adversity of war.

On the battlefield, Kenyan troops contributed in all capacities. Most served as infantry – riflemen, machine-gunners, mortar crews – clearing Japanese bunkers and patrolling hostile trails. Others were scouts, sappers, or porters. A Kenyan signaler, Sgt. Gershon Fundi, carried a wireless radio through the jungle to keep units connected. Kenyan drivers and mechanics in the Royal East African Corps kept jeeps and supply trucks running over impossible roads. Some even manned anti-aircraft guns protecting Allied positions from Japanese aircraft. British General William Slim, who commanded the 14th Army, lauded the “valor and reliability” of his African soldiers and later argued that they had proven themselves equal to any troops in the Empire. Indeed, by helping to secure Burma, the Kenyan askaris and their African comrades played a significant role in one of the longest, toughest campaigns of World War II – even if their role remained largely out of the spotlight.

Challenges and Experiences of the Kenyan Askari

For the Kenyan soldiers, the Burma campaign was not only a clash of armies but also a profound personal journey. They were fighting in an alien land far from home, with unfamiliar languages and customs. The jungle’s dangers were constant: enemy ambushes, booby traps, and sniper fire turned each march into a life-or-death ordeal. “Burma was tough – bullets were just raining on us,” recalled Muchara Ntiba, a Kenyan veteran in his late 90s, of the battles against Japanese troops. Close-quarter combat in the thick vegetation was often brutal and chaotic. Yet many Kenyans displayed remarkable steadiness under fire. British officers noted that once properly trained, African askaris had high natural battle discipline – they would hold the line and press attacks even after taking casualties.

Racism and cultural barriers added to the challenges. The Kenyan askaris served in a segregated colonial army; all African soldiers were led by white officers and a few white NCOs, since blacks were not permitted to rise above the rank of warrant officer in that era. Within the wider 14th Army in Burma, the East Africans often sensed they were treated as an afterthought. A war correspondent embedded with the 11th Division observed critically that “14th Army were notoriously bad in their efforts to do anything for African troops”, noting that supply depots in India failed to provide even basic comforts or appropriate gear for the askaris. Unlike Indian units, the African formations had no local community or political lobby to champion their needs in the rear areas. This meant Kenyan soldiers sometimes lacked proper food (they often received unfamiliar rations), suitable boots and clothing for the jungle, or even recreational facilities when out of the line. Some British personnel, sadly, showed open contempt – one South African woman in the service, encountering West African troops on a stopover, crudely asked an officer, “You don’t arm these monkeys, do you?”. Such racism stung, but the askaris persevered regardless.

Moreover, Kenyan soldiers had to navigate complex relationships with the local Burmese population. Most villagers in Burma had never seen Africans before, and vice versa. Communication was usually through English or gestures, since few askaris spoke Burmese. Yet there were instances of mutual compassion: African troops sometimes shared their rations with starving Burmese civilians, and there are recorded stories (especially in the Arakan campaign) of local people sheltering wounded African soldiers. These moments of humanity provided some relief from the war’s brutality. Nonetheless, cultural isolation was real. Many Kenyans felt a deep longing for home – a sentiment Mbiuki voiced every time he prayed to survive another day in the jungle.

Despite everything, the Kenyan askaris kept their spirits through brotherhood and faith. They sang marching songs in Swahili to keep morale up on long treks. They observed their religious practices as best as they could – Christians held makeshift church services in the field, and Muslims among the askaris celebrated Eid far from their families. Letters from home were rare, but when they arrived they caused great excitement in camp (one British captain remarked how “a man who brings news from home” could instantly cheer an African unit). Many Kenyans also found pride in proving themselves on equal footing with British and Indian troops. They knew they were part of a grand Allied effort to defeat fascism, even if few back in Kenya fully understood why their sons were fighting “for the British” in a place as far away as Burma. The Kenyan soldiers’ resilience under such multifaceted challenges – environmental, racial, emotional – stands as a testament to their character.

Casualties and Honors

The Burma campaign took a painful toll on Kenya’s soldiers. Hundreds of Kenyans lost their lives in the jungles of Southeast Asia, and thousands more were incapacitated by wounds or tropical diseases. Precise figures for Kenyan casualties in Burma are hard to determine (as records usually grouped all East African losses together), but overall the 11th (East Africa) Division and related units suffered substantial attrition during 1944–45. In one phase of the fighting, for example, an East African brigade had to evacuate over 500 sick troops in a month while engaging in constant skirmishes. Malaria, dysentery, and scrub typhus were rampant; for every East African soldier killed or injured by the enemy, many more were struck down by illness. By the war’s end, a significant number of Kenyan veterans bore lifelong scars – from amputations and bullet wounds to recurring malarial fevers and psychological trauma.

While their sacrifices went largely unheralded at the time, some Kenyan and East African askaris did receive formal honors for bravery and service. British high command awarded numerous Africans gallantry medals in Burma, though often these recognitions were lesser in profile than those for European troops. For instance, African non-commissioned officers received Distinguished Conduct Medals and Military Medals for acts of courage under fire. A notable example is Sergeant Yowana of the 4th (Uganda) Battalion, KAR, who earned the Military Medal in 1945 for “bravery in the field” during the Burma campaign. Kenyan askaris likewise earned Military Medals and Mentions-in-Dispatches for leadership and gallantry, though none received Britain’s highest award (the Victoria Cross) in this theater. It is worth noting that the King’s African Rifles as a whole expanded to 44 battalions by 1945 to meet the war’s demands, and by then Africans had been integral to victory in multiple arenas. The East African soldiers’ achievements – crossing the Chindwin, helping capture strategic objectives like Myohaung (in Arakan), and relentlessly pursuing the retreating Japanese – were praised by Allied leaders. The British Parliament’s Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Devonshire, lauded the Kenyan and East African troops in a 1945 speech, highlighting their confidence and calling their monsoon march “an achievement of the impossible”. Such tributes, however, were fleeting, and in post-war histories the African contribution unfortunately received scant attention.

By late 1945, the surviving Kenyan soldiers were gradually rotated back home. The 11th (East Africa) Division was fully withdrawn and returned to East Africa at the end of 1945, once Japan had surrendered. The long journey by sea back to Mombasa and the subsequent demobilization ceremonies in Nairobi marked the end of their military service abroad. Many came home with service medals like the Burma Star, a campaign medal awarded to all Allied personnel who served in Burma. But a ribbon on the chest was scant compensation for the toil and loss they had endured.

Post-War Legacy in Kenya: “Forgotten Heroes”

When Kenyan veterans of Burma stepped off the troopships and back onto Kenyan soil, they encountered a home that was in many ways unchanged – and ungrateful. The grand promises made to them during the war – of a better life, land, or political voice – evaporated. As former askari Kango Muchai bitterly noted, “we Africans were told over and over again that we were fighting for our country and democracy and that when the war was over we would be rewarded… The life I returned to was exactly the same as the one I left four years earlier: no land, no job, no representation, no dignity.” Many veterans found that while they had been off fighting, colonial policies had not improved at home. In some cases things had worsened – white settlers in Kenya had even appropriated more African land during the war years. Rather than receiving heroes’ welcomes, most Kenyan ex-soldiers struggled to reintegrate into a society still ruled by racial segregation and economic inequality.

Economic hardship hit returning askaris quickly. The British colonial government gave each demobilized soldier a one-time payout called a war gratuity – but this was calibrated by race in the most blatantly unfair way. A British ex-serviceman from Kenya received a much larger sum than an African of the same rank. African veterans’ gratuities were deliberately lower, in line with the racial hierarchy the Empire maintained. Ongoing pension payments were often denied entirely to black African soldiers. Despite wartime appeals by commanders like General Slim to treat African troops fairly, colonial authorities decided that most African askaris did “not need” service pensions, dismissing them as “natives” who could return to subsistence livelihoods. This betrayal left many Kenyan veterans destitute. As Sgt. Gershon Fundi recalled, “We put our lives in danger for Britain… But the British government did not listen to our demands. We got out with nothing.” His words typified the sense of abandonment felt by those who had given so much.

Socially, these veterans also faced challenges. They came back changed men – having traveled the world, seen modern warfare, and shed blood alongside Europeans and Indians, they were far less willing to accept second-class status at home. Yet the colonial system expected them to quietly resume their old lives. Tensions simmered as ex-askaris competed with the growing population of educated Indian Kenyans for the scarce jobs in towns. Many veterans ended up jobless or took menial positions far below the responsibility they had held in the army. Some, traumatized by their experiences, found it hard to settle at all. Families noticed changes: post-traumatic stress (though not diagnosed as such then) afflicted men who had survived months of combat and jungle terror. “He came back unwell,” remembered Grace Mbithe of her husband Stanley, a Kenya KAR veteran. “At night we couldn’t sleep… If he heard rain while we were sleeping, he would get up, he would go outside and it would rain on him over and over again, while his heart beat faster and faster.” The nightly downpour in Kenya’s highlands would trigger her husband’s dreadful memories of monsoon nights under fire in Burma. Countless other families quietly bore similar burdens, as the war’s mental scars lingered for years.

On a broader scale, the return of veterans had political ripples in Kenya. In 1944, as the war was ending, Africans in Kenya were for the first time allowed to form a nationwide political organization. The Kenya African Union (KASU, later KAU) emerged to demand greater rights and eventual independence. While relatively few ex-soldiers formally joined KAU, many were drawn into activism or at least lent sympathy to those agitating for change. The confidence and worldly perspective Kenyan veterans gained made them less fearful of confronting colonial authorities. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, some veterans indeed took part in the Mau Mau movement or other anti-colonial protests, bringing with them military training and leadership skills. The colonial government grew wary of the very men it had trained – in one instance, ex-askaris were placed under surveillance for seditious activities. The irony was not lost on the veterans themselves: they had fought to defend the British Empire, and now that same empire treated them as potential subversives.

For decades after WWII, the story of the Kenyan (and African) soldiers in Burma remained largely forgotten or ignored by the public and even by historians. There were no memorials erected in Nairobi for them, no annual honors comparable to those for European soldiers. In British war histories, the African divisions received only passing mentions (sometimes with embarrassing errors). One authoritative account of the Burma War misidentified the 81st West African Division as an East African unit and barely noted the African units at all. This lack of recognition was acutely felt by the veterans. As late as the 1980s and 1990s, aging Kenyan ex-askaris would gather in small reunions to remember their fallen comrades, often lamenting that their contributions had been erased from official history. They referred to themselves as the “Forgotten Army’s forgotten soldiers”, highlighting that even the Burma campaign — dubbed the “Forgotten War” in Britain — managed to forget the Africans who fought in it.

Only in the XXI century did their plight start gaining more attention. Investigative reports and books highlighted the injustice faced by African WWII veterans. In 2018, the UK government finally announced a modest £12 million compensation package for Commonwealth veterans in poverty, including some of the few surviving Kenyans. In Kenya, a new generation of scholars and descendants began collecting oral histories from the old soldiers, determined to preserve their stories. These efforts have led to a re-appraisal of Kenya’s role in the war. For example, authors like Timothy Parsons and David Killingray have documented how the war experience radicalized Kenya’s soldiers and influenced the path to independence. Public ceremonies have also started to acknowledge African veterans. On V-J Day (Victory over Japan Day) anniversary events, one now occasionally sees Kenyan and other African ex-servicemen mentioned alongside their British and Indian comrades, correcting the historical record.

Still, for most of the Kenyan Burma veterans, these changes came very late. As one Kenyan signalman, reflecting on his service, stated: “If you ran [from conscription], chiefs would arrest you and bring you back… How can you complain? We have no voice, we have no voice at all.” In those words lies the poignant truth: the Kenyan soldiers had done their duty bravely, but afterward, they had no voice to advocate for themselves. It took over 70 years for that voice to begin being heard.

Conclusion

The Kenyan soldiers who fought in the Burma campaign of World War II were part of a broader African contingent that made a vital contribution to the Allied victory in Asia, even as they remain under-recognized in history. Their journey from the villages of Kenya to the jungles of Burma is a story of courage, sacrifice, and resilience. They answered the call to fight a distant war, and in Burma’s steamy rainforests they proved themselves tenacious jungle fighters, expert bridge-builders, and steadfast comrades-in-arms. They suffered tremendous hardships from climate, disease, and combat, and many paid the ultimate price far from home. Those who survived returned to a colonial society that was unprepared to reward or even adequately acknowledge their service. Yet, in the long run, their experiences helped sow the seeds of change in Kenya – emboldening a generation that would soon demand freedom and equality.

Today, as we look back, the Kenyan askaris in Burma stand as heroes who should no longer be forgotten. Their story adds an important chapter to Kenya’s national history and to the global history of World War II. Whether it is the image of determined young Kenyans laying timber over a mud road under monsoon rains, or an old veteran’s recollection of praying for the chance to see home again, these narratives humanize the vast scale of WWII. They remind us that the fight against tyranny was truly worldwide, and that Kenya’s sons, in their own quiet way, helped to secure the peace that followed. It is only fitting that we honor their legacy – not just with medals or belated compensation, but by remembering their story and teaching future generations about the Kenyan soldiers in the Burma campaign who fought, died, and lived for a freedom they themselves would ultimately struggle to enjoy.

Sources: Historical accounts and veterans’ testimonies have been drawn from reputable archives and publications, including the Imperial War Museum, the King’s African Rifles Association, the Guardian (“Forgotten African soldiers” series), academic works on the Burma campaign, and writings by researchers like Charlie Gilbert and Harry Fecitt who have documented the East African forces’ role in WWII. These sources help ensure that the valor and sacrifice of Kenyan soldiers in Burma are preserved in the annals of history, no longer forgotten.

Read Next

- The Battlefield Around the Railway: East Africa’s Forgotten WWI Front

- Kenya in the First World War: Carrier Corps and the Forgotten Front

- The Hola Massacre: When British Colonial Brutality Was Laid Bare

- Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, 1952–1960

- The Shifta War: Kenya’s Forgotten Border Conflict, 1963–1968