One sunny afternoon in Nairobi, a skeptical bank customer named Wanjiku stared at her SMS banking alert. Her paycheck of KSh 50,000 had just been deposited into her account at Co-operative Bank. A comforting message assured her: “Dear Customer, your funds are safe with us.” But Wanjiku couldn’t shake a nagging question: How can her money be safe in the bank if the bank is lending it out to other people? For years, she’d heard the common story – “banks take your savings and lend them to borrowers.” Yet something didn’t add up. Her account still showed KSh 50,000 available, even if the bank had supposedly given that money to someone else as a loan. Was the bank magic, or was there a hidden trick in how money works?

Wanjiku’s curiosity set her on an investigative journey. Like many Kenyans, she had trusted banks without really understanding what happened behind the counters and computer screens. Now, she was determined to demystify the process. Armed with questions, she imagined herself as a detective of finance, ready to follow the money trail. Is it true that banks simply move money from savers to borrowers? If not, where does the extra money come from when the economy grows and banks seem to lend far more than the cash they hold?

This is the story of what Wanjiku discovered – a story of how commercial banks in Kenya actually create money, digitally and almost out of thin air. It’s a journey through vaults and ledgers, from the village chama to mobile loan apps, uncovering the truth that most of us never learned in school. By the end of it, the mystery of the magical money machine will be revealed in simple terms, with real examples from Kenyan banks (including Co-operative Bank’s own financial statements) and the mobile lending boom that has swept the country.

Brace yourself: you might never look at your bank account or M-Pesa wallet the same way again.

“We Just Lend Out Your Savings”

To begin, Wanjiku revisited what she thought she knew. The traditional story told by teachers, bank brochures, and even parents is that banks are vaults: you deposit your savings, and the bank loans part of those savings to others. In this story, banks are seen as mere intermediaries – passing money from Point A (savers) to Point B (borrowers) and charging a little interest along the way. It’s a comforting narrative, implying that all loans are backed by someone’s hard-earned deposits. After all, “money doesn’t grow on trees,” right? A bank can’t lend money it doesn’t have… or can it?

Wanjiku recalled her mother’s advice when she opened her first account: “The bank will keep your money safe, and use it to help others get loans. That interest they earn pays you a little something too.” This makes sense on the surface. If Wanjiku deposits KSh 50,000 and her friend Otieno borrows KSh 50,000 from the same bank, one might imagine the bank simply took Wanjiku’s cash and handed it to Otieno. Wanjiku’s account would then go down to zero until Otieno repays. But in reality, Wanjiku’s account balance doesn’t drop at all when the bank makes that loan to Otieno. She can still see her full KSh 50,000 and withdraw it anytime. How is that possible?

This is where the mystery deepens. Wanjiku started suspecting that the bank wasn’t being entirely transparent about the process. If her money never left her account, yet Otieno also got money, then two people now have claims to what was the same money. The total money in the system seemingly doubled from KSh 50k to KSh 100k. Wanjiku mused, “Are banks creating money when they lend? It sounds absurd, like a con game or a magic trick.” Her inner skeptic was on high alert.

She decided to dig deeper. How can two people own the same shilling at once? Either the bank had cloned her shillings, or the common story was leaving out a big part of the truth. It was time to follow the shillings and find out where they really come from.

A Step-by-Step Reveal of Money Creation

Wanjiku’s investigation led her to a simple thought experiment, guided by an friendly bank officer who agreed to walk her through it. “Let’s create a tiny imaginary economy with just you and a few others,” he said. “This will show how banks create money step by step.” He laid out the scenario:

- Wanjiku deposits KSh 1,000 in cash at Bank A. This is real physical money she earned and now places in the bank. The bank credits Wanjiku’s account with KSh 1,000. (At this moment, total money in the system is KSh 1,000 – all in Wanjiku’s digital account, backed by the KSh 1,000 note the bank holds in reserve.)

- The bank keeps a fraction and lends the rest. In Kenya, banks are required to hold only a small fraction of deposits as reserves (for simplicity, say 10% in this example, though the actual required ratio has been around 5% in recent years). So Bank A sets aside KSh 100 (10%) as a reserve – part of which might stay as cash in the vault or as deposit at the Central Bank – and loans out KSh 900 to another customer, Otieno. Importantly, this KSh 900 isn’t taken from Wanjiku’s balance – her account still shows KSh 1,000. The KSh 900 is newly created as a loan to Otieno, and simultaneously a new deposit in Otieno’s account. Otieno now has KSh 900 in his account to spend, even though Wanjiku still has KSh 1,000 in hers. Total money in the system has grown to KSh 1,900 (Wanjiku’s 1,000 + Otieno’s 900). The bank effectively conjured KSh 900 out of thin air by crediting Otieno’s account, trusting that Wanjiku won’t suddenly withdraw her whole KSh 1,000 at the same time.

- Otieno pays Akinyi KSh 900 for some supplies (transferring his loan money to someone else). Akinyi receives this KSh 900 payment and deposits it in Bank B (perhaps Akinyi uses Equity Bank or even another branch of Bank A – the principle is the same). Now, Bank B has KSh 900 new deposit. Notice: Wanjiku still has KSh 1,000 in Bank A, and now Akinyi has KSh 900 in Bank B. The money supply is still KSh 1,900 in total digital deposits.

- Bank B can now repeat the cycle. It keeps 10% of the KSh 900 (that’s KSh 90) as reserves, and lends out the remaining KSh 810 to another borrower, say Nyambura, by simply crediting Nyambura’s account. Nyambura spends the KSh 810, which then gets deposited by someone else into Bank C. Now Bank C has a new deposit of KSh 810.

- And on it goes… Bank C keeps 10% (KSh 81) and loans out KSh 729 to the next person. The next deposit is KSh 729, and then KSh 656 gets loaned out, and so on in a diminishing sequence.

If you sum up all these rounds, something astonishing emerges: that original KSh 1,000 in cash Wanjiku deposited can end up creating roughly KSh 10,000 in total money circulating in the banking system (in our 10% reserve example). If the reserve requirement was even lower – say 5% – the same KSh 1,000 could theoretically grow to KSh 20,000 in the banking system. This phenomenon is often called the fractional reserve multiplier – a fancy term for the process we just walked through in plain language.

Wanjiku was floored by this realization. It truly sounded like money was being created out of nothing but book entries. And indeed, that’s exactly what was happening. “So my KSh 1,000 can support ten people each having about a thousand shillings in their accounts through this chain reaction,” she murmured. The bank officer nodded, “You’ve got it. Every time we issue a loan, we create a deposit in the borrower’s account. We don’t grab that money from someone else’s savings; we just write it into existence, within the limits allowed by regulations and our own prudential rules.”

In that moment, Wanjiku felt like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, peeking behind the curtain at the great money-making machine. The truth was both simple and startling: banks don’t just lend out deposits – banks create new deposits when they lend. Or as economists like to put it, “loans create deposits.”

Banks Create Money (Yes, Really)

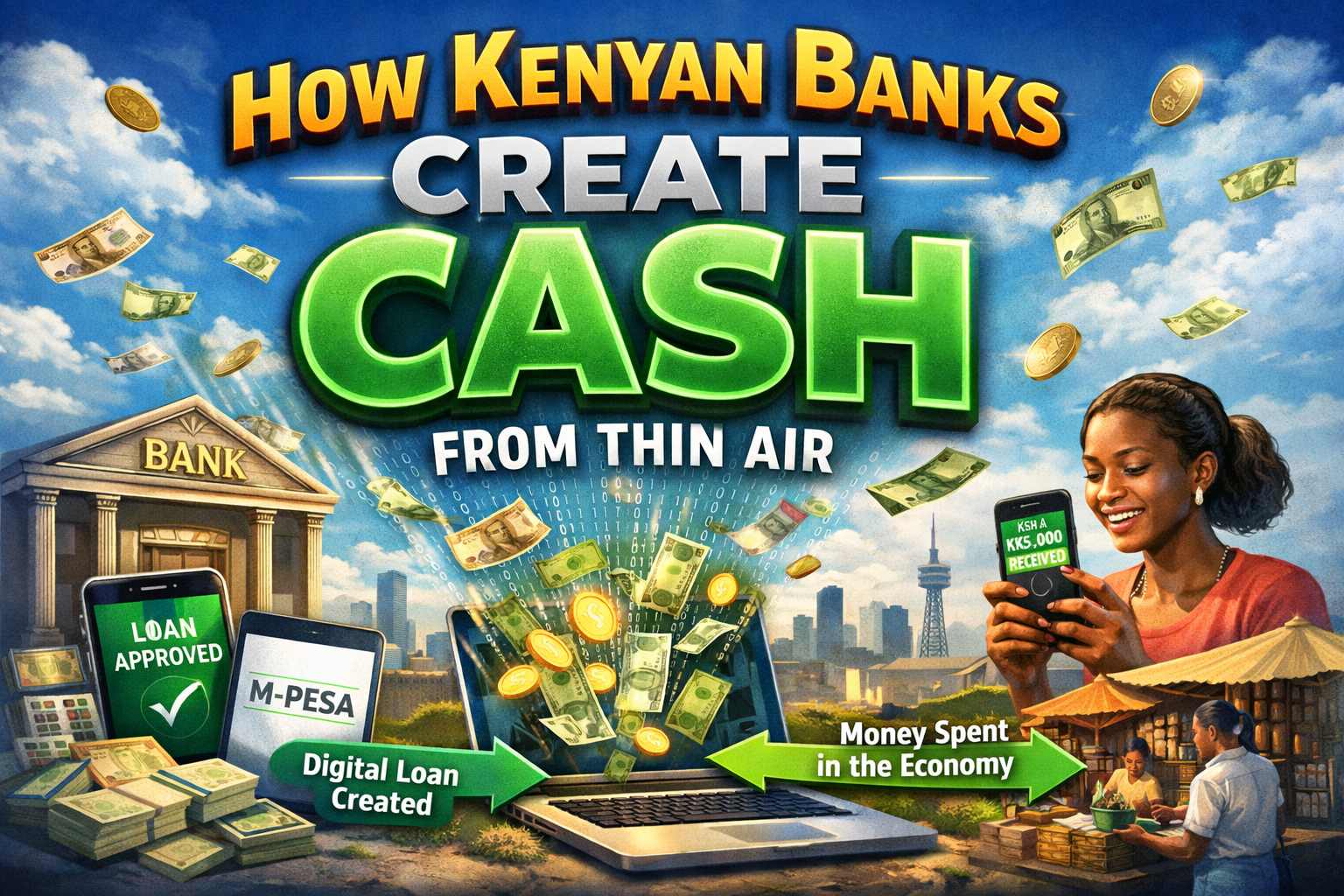

After seeing the step-by-step example, Wanjiku sought confirmation from authoritative sources. Was this just a theoretical trick, or do real bankers and economists agree that banks create money? It didn’t take long to find proof. The Bank of England, for instance, openly explains that “the majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans”. In fact, “whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s account”. This isn’t fringe theory – it’s how modern banking functions worldwide.

Closer to home, Wanjiku found a Kenyan financial commentator breaking it down in plainer English. He lamented that viewing banks as mere intermediaries between savers and borrowers is “so incorrect as to be outright misleading.” No one’s account actually gets debited to fund a new loan, he noted. “No depositor has ever had their bank balance reduce because the bank lent out what they had deposited,” he wrote. Instead, “The simple truth is that banks create new deposits when they issue credit… The amounts credited into a customer’s account when they borrow from a bank do not come from the government, or from depositors’ accounts. They are created at the point of lending.” In other words, new digital money is born the minute your loan is approved and hits your account.

Wanjiku re-read that statement twice. It was exactly the answer to her mystery. The money for loans isn’t sitting in a vault or taken from Auntie Njeri’s fixed deposit; it’s new money recorded in the bank’s computer system, backed by the borrower’s promise to pay it back. The bank essentially manufactures purchasing power for the borrower, and in doing so increases the total money circulating in the economy.

How much of our money is created this way? The numbers stunned her. In Kenya, as in most modern economies, the vast majority of money is not cash minted by the government, but bank-created deposits. At the end of 2022, all the physical cash (notes and coins) in Kenya was about KSh 258.8 billion, while the total money supply (in economic terms “M2” which includes cash, checking accounts, savings, mobile money balances, etc.) was about KSh 3.6 trillion. Do the math – only around 7% of Kenyan money exists as tangible cash; a whopping 93% exists as entries in bank accounts or mobile wallets. And according to that analyst’s research, about 93% of Kenya’s money (M2) – roughly KSh 3.3 trillion – had been created by commercial banks through the lending process as of December 2022. Ninety-three percent! The remaining few percent was the hard cash printed by the Central Bank or the government.

With this revelation, Wanjiku felt as if a veil had been lifted. She imagined every loan contract as a sort of magic wand: when a bank officer signs off a loan, poof! – a new deposit appears in someone’s account, increasing the total money in circulation. Of course, there’s no free lunch; the borrower now owes the bank that money, with interest, so it’s a loan that must be repaid. If loans are paid off or written off, that money effectively “disappears” from the money supply. But day to day, as banks issue more new loans than the loans that are being repaid, the money supply grows and the economy has more spending power.

John Kenneth Galbraith, a famous economist, once quipped: “The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled.” Indeed, Wanjiku smiled at how true that is – it’s such a straightforward accounting maneuver, yet it feels counter-intuitive. Important things in life are supposed to be complicated, and here was perhaps the most important engine of the economy – money creation – happening with a mere keystroke in banking software. It’s simple, but it was kept in a shroud of mystery for so long.

The Co-operative Bank Example

By now, Wanjiku was convinced on a theoretical level. But she wanted to see this in the real world of Kenyan banking. She decided to look at actual financial statements of a Kenyan bank to find evidence of this “money from thin air” phenomenon. Fortunately, banks publish their financial statements regularly. She got her hands on a summary of Co-operative Bank of Kenya’s financial position from mid-2022 (a publicly available report). The numbers told a clear story:

- Customer Deposits: Co-op Bank held about KSh 412.8 billion in customer deposits as of June 30, 2022. This is the money that customers like you, me, and Wanjiku have in our accounts, which the bank owes to us on demand.

- Loans to Customers: The bank had about KSh 323.94 billion lent out as loans to customers at the same time. This is money that borrowers owe the bank (the bank’s assets).

- Cash on Hand: How much actual cash do you think the bank had in its vaults and tills? Only about KSh 6.64 billion in local and foreign currency cash. Yes, just 6.6 billion – that’s roughly 1.6% of the customer deposits.

- Reserves at Central Bank: Additionally, Co-op Bank had about KSh 17.02 billion parked as reserves at the Central Bank of Kenya (essentially the bank’s own “savings account” with the central bank). Banks keep some reserves with the central bank to meet regulatory requirements and facilitate transactions with other banks.

For a clearer picture, Wanjiku summarized the key figures in a simple table:

| Co-operative Bank (June 2022) | Amount (KSh billions) |

|---|---|

| Customer deposits (what it owes customers) | 412.8 |

| Loans to customers (what customers owe it) | 323.9 |

| Cash in vaults & ATMs (actual hard cash) | 6.6 |

| Reserves at Central Bank of Kenya | 17.0 |

Look at the disparity: KSh 412.8 billion in deposits versus only KSh 6.6 billion in actual cash! The rest of the deposits have been transformed into loans (KSh 323.9B) or are held in other forms like government securities or balances with other banks. Yet every one of Co-op’s deposit customers sees their full balance on their statements and can theoretically demand their money. If all those customers simultaneously asked to withdraw everything, clearly the bank would not have anywhere near KSh 412 billion in cash to hand out. This is not a scam; it’s just how fractional-reserve banking works. Co-op Bank, like all banks, operates on the assumption (backed by experience and regulation) that on any given day, only a small percentage of deposits will be withdrawn in cash. Most money will stay in digital form or get transferred bank-to-bank rather than being taken out as physical cash.

Wanjiku found this both fascinating and a bit unsettling. The Co-op Bank data solidified the concept: our deposits are mostly loaned out or invested elsewhere, yet we all act like our money is just sitting there for us. In truth, it’s out working in the economy – financing someone’s boda boda loan, someone’s mortgage, a company’s expansion, or the government’s Treasury bonds. The bank has essentially promised all of us that our money is available on demand, while knowing that it’s impossible for everyone to demand it at once. It’s a careful balancing act, underpinned by trust and confidence. As long as people believe in the bank and don’t all rush to pull out their money at the same time, the machine functions smoothly. If that trust falters… well, more on that soon.

Before diving into the risks, Wanjiku reflected on one more thing she noticed in Co-op’s statements. The bank’s loans (KSh 323.9B) were less than the deposits, which is typical – banks don’t lend all deposits; they also hold assets like government securities and maintain capital buffers. But importantly, the loans were far greater than the bank’s cash holdings. This is by design. Banks earn most of their income by lending money (which yields interest) rather than holding cash (which yields nothing, and can even be a cost). So they lend out as much as prudently possible. In Co-op’s case, only about 1 out of 62 shillings of deposit was kept as cash in June 2022 (roughly 1.6%). The rest was out earning interest or serving other needs. In fact, Co-op Bank’s total assets (everything the bank owns including loans, cash, investments) were about KSh 560 billion, and its total liabilities (mostly customer deposits) were about KSh 507 billion, with the difference being shareholder’s equity – a cushion of capital. The bank was solvent and profitable. This ease with which deposits become loans and investments is exactly how modern banks create wealth (and profit) – but it only works in a stable environment where people don’t panic.

Having uncovered how banks conjure money digitally through loans, Wanjiku next wondered: What changed in recent years with the advent of mobile money and digital loans? Has this money creation machine gone into overdrive in Kenya’s new fintech era? The answer, she would find, is yes – and it’s a double-edged sword.

Money Unchained from Physical Cash

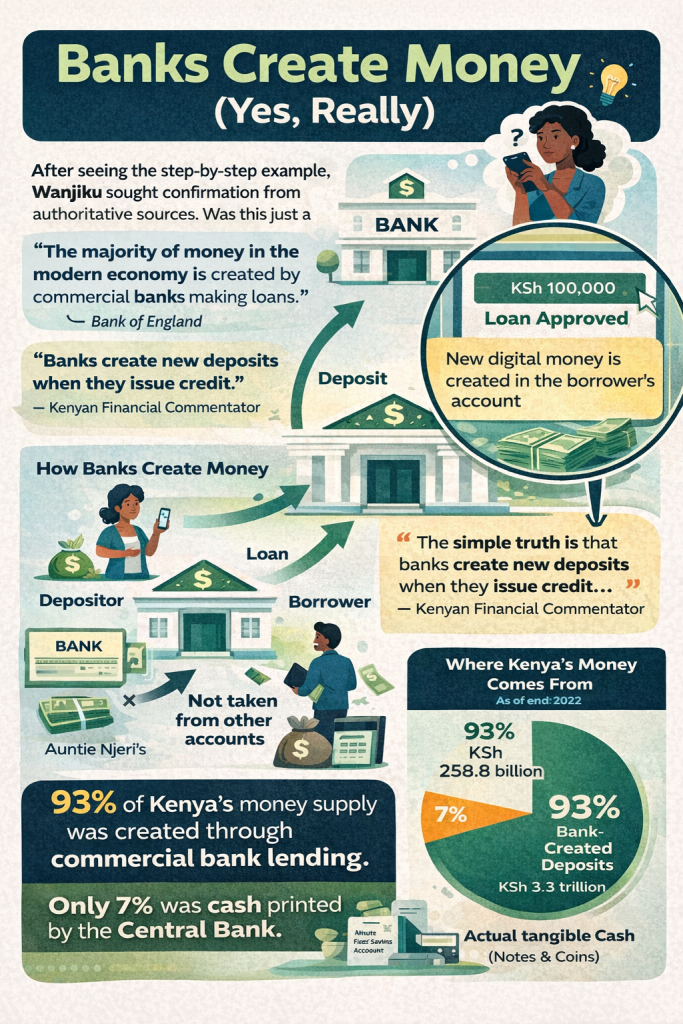

Kenya’s financial landscape transformed dramatically after 2007 with the launch of Safaricom’s M-Pesa, the mobile money service that let anyone send money with a simple SMS. Wanjiku remembers the early days of M-Pesa as a marvel – no bank account needed, no long queues to send or receive cash; just a few taps on the phone. Over time, M-Pesa became ubiquitous. By 2023, the M-Pesa ecosystem was handling mind-boggling volumes: 28.3 billion transactions worth KSh 40.2 trillion in a year. (Yes, trillion with a T – that’s more than three times Kenya’s annual GDP coursing through phones, a testament to how many times each shilling changes hands digitally.)

So how did M-Pesa help banks create and circulate more money with fewer physical constraints? The key is that M-Pesa turned money into a fully digital form for the masses. Cash could now stay within the system as a mobile wallet balance indefinitely, rather than being withdrawn as banknotes. Essentially, fewer people need to withdraw physical cash when they can pay for matatu fare, buy groceries, or pay utility bills straight from their phone. This reduces the banks’ need to physically provision cash. A shilling can circulate electronically through dozens of transactions (via M-Pesa or bank transfers) without ever being converted to hard cash. This lubricates the money creation engine – banks can expand the digital money supply (by lending) with even less worry about running out of paper currency.

Another impact of M-Pesa was that it brought millions of unbanked Kenyans into the formal monetary system. Someone in a village who kept cash under the mattress now might keep e-money on M-Pesa. That e-money itself is backed by trust accounts in banks. (Safaricom holds the equivalent value of all M-Pesa deposits in several commercial banks for safety). Now, consider a person who never had a bank account but uses M-Pesa daily. This person can now also access banking services through their phone – and that’s exactly what happened with products like M-Shwari and KCB M-Pesa.

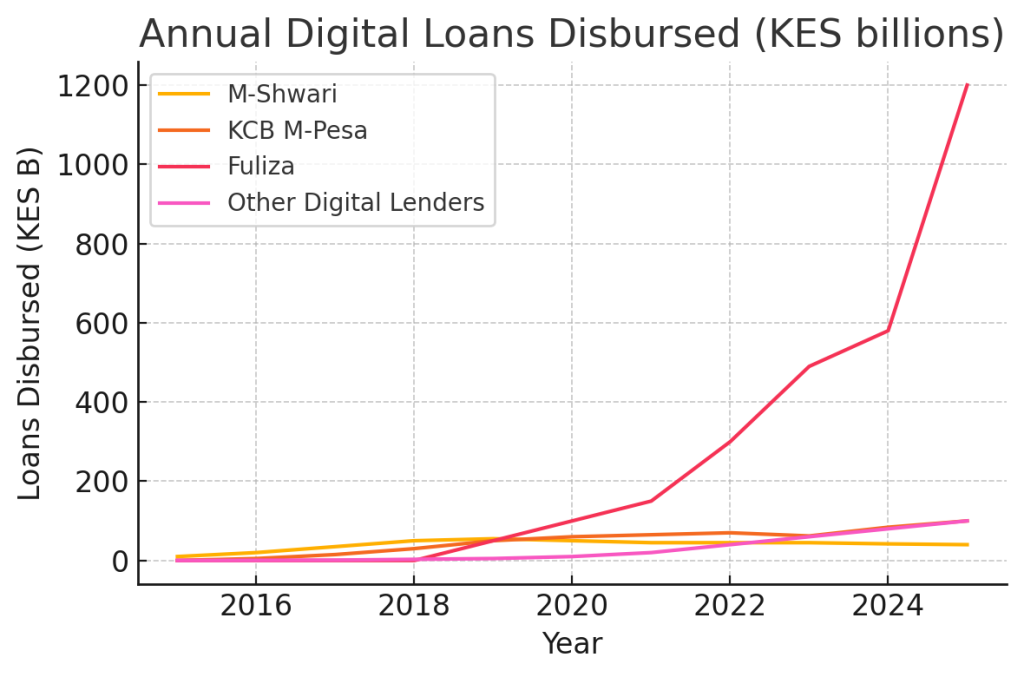

M-Shwari (launched 2012 by Safaricom and CBA, now NCBA) and KCB M-Pesa (launched 2015 by Safaricom and KCB) were revolutionary: they offered savings and loans via the phone to M-Pesa users. No need to visit a bank branch or fill lengthy forms. If you had an M-Pesa account and a phone, you could get a loan in seconds. Wanjiku herself recalled TV ads for KCB M-Pesa – it sounded so easy, almost too good to be true. And Kenyans embraced it. Between 2018 and 2022, KCB disbursed 40 million mobile loans totaling KSh 332 billion through KCB M-Pesa and related digital platforms. That’s 332 billion shillings of new credit injected largely to folks who tapped a few buttons on their phones. Traditional banking could never have delivered so many loans so quickly without the digital conduit.

Safaricom’s own foray, Fuliza, introduced in 2019, took things even further by providing an overdraft on the M-Pesa wallet. If you didn’t have enough balance to pay for something, Fuliza would instantly lend you the shortfall so the transaction goes through. By design, Fuliza was meant for very short-term lending (often repaid when your next income or transfer comes in). Kenyans leapt on this facility with gusto – perhaps too much gusto. By early 2024, Safaricom’s data showed KSh 2.3 billion was being borrowed per day on Fuliza! That means every single day, over two billion shillings of fresh credit is created and funneled into people’s M-Pesa wallets via Fuliza. In the financial year ending March 2024, Fuliza disbursements totaled about KSh 834 billion (up from 701 billion the previous year). These numbers are enormous – Fuliza alone is like a money hose spraying credit continuously into the economy’s engine.

And it’s not just Fuliza. Other digital lenders like Tala and Branch (popular smartphone apps) have been offering quick loans to individuals, completely outside the traditional banking model. They don’t take deposits from users; instead, they use investor funds or bank credit lines to lend, but from a borrower’s perspective it feels the same – a few clicks and money appears in your mobile wallet. By the late 2010s, Nairobi’s young professionals joked that whenever they were broke before month-end, they’d go fishing in the “Tala-Branch ocean” or “Fuliza it” to survive. These services were lifesavers for emergencies – but they also made debt extremely easy to fall into.

So, what changed in the economy with all this? In short: money circulated faster and reached more people, but it also led many into a cycle of borrowing. The ease of digital money lowered the physical barriers – you no longer had to walk to a bank, fill forms, wait days for loan approval, or even have collateral in many cases. A whole segment of the population that banks once found too costly to serve (small borrowers, informal workers) could now be reached at scale through an app. This meant banks and fintech firms could expand their lending (money creation) far beyond the traditional customer base. The result was a credit boom at the micro level: millions of tiny loans flowing every day, oiling the wheels of commerce and consumption.

Wanjiku noted two sides to this coin. On one hand, financial inclusion improved – a vegetable vendor in Kiambu or a student in Mombasa could now get a small loan to buy stock or pay school fees, where previously they might have had no access to credit at all. On the other hand, the risk of over-lending and over-borrowing also shot up. Digital platforms were giving loans without the kind of diligence banks used to apply for larger loans. There’s no loan officer personally interviewing you for a KSh 5,000 Fuliza advance. It’s automated and instant. This convenience meant people could easily slide into taking loan after loan, sometimes from multiple providers concurrently. It was like the money creation machine got a turbo boost – but with turbo speed comes the risk of crashes.

Debt Traps and Bank Runs

By now, Wanjiku understood how banks create money and how digital innovation accelerated that process in Kenya. Her next question was sobering: What are the dangers? Every magic trick has a peril if something goes wrong – the lovely assistant could get sawed in half for real if the magician isn’t careful. Likewise, the banking system’s magic of money creation comes with inherent risks that both individuals and society must reckon with. Here are the key risks Wanjiku uncovered:

1. Digital Over-Lending and Personal Debt Traps

When loans are a few clicks away, there’s a temptation to borrow repeatedly – even for non-essential or recurring needs. Kenya’s digital lending boom shows a worrying pattern: many people use these loans to cover daily expenses, not just rare emergencies. Studies found that over 80% of digital loans in Kenya are used for basics like food, rent, or school fees, rather than for investing in a business or asset. Essentially, people are borrowing to get by, then often borrowing again to repay previous loans – a cycle of debt dependency. It’s not uncommon to hear of someone who took a Tala loan to clear a Branch loan, or used Fuliza to pay off an M-Shwari loan. This is sometimes called debt stacking, and it creates a closed loop of borrowing without relief.

For the individual, this can quickly turn into a debt trap. The interest rates on digital loans are quite high – one Kenyan Banker’s Association report noted some mobile lenders charge up to 30% interest for a one-month loan. Annualized, that’s an astronomical rate, and it means a borrower who is even a few days late can see their debt snowball. The ease of getting the loan is replaced by the agony of repayment. According to CGAP surveys, 83% of digital borrowers in Kenya experience stress about repaying their loans. Wanjiku could believe it; she had a cousin who once juggled three different app loans and was getting constant SMS warnings of overdue payments – it was a source of huge anxiety.

This over-lending is risky not just for borrowers but for lenders too. If enough people default, the lenders (whether banks or fintechs) take a hit. Many digital lenders in Kenya saw high default rates, and the Central Bank of Kenya stepped in with new regulations in 2022 to rein in unregulated digital loan apps that were mushrooming everywhere. Lenders now must be licensed and adhere to customer protection rules. The frenzy has cooled a bit, but digital loans are very much here to stay, and Kenyans are learning the hard way that easy money can come at a steep cost.

2. Liquidity Mismatch: The Bank’s Balancing Act

Remember how only a small fraction of deposits is kept as cash or liquid assets? That’s called a liquidity mismatch – banks lend long-term (your loan might be 1-5 years to repay) but fund themselves short-term (your deposits could be withdrawn tomorrow). This model works only as long as the majority of depositors don’t demand their money at the same time. It’s a confidence game: banks need depositors to feel secure and leave their money parked. If that confidence is shaken, the whole house of cards can wobble.

Wanjiku found a dramatic Kenyan example of this: Chase Bank (Kenya) in 2016. Chase Bank was a mid-sized, seemingly successful bank. But when news broke of some irregularities (like large insider loans that weren’t properly reported), depositors got nervous. Thanks to WhatsApp and Twitter, panic spread fast. In one day, customers withdrew about KSh 7.6 billion from Chase Bank – a classic bank run. The bank simply could not meet all these withdrawals; it ran out of ready cash and liquidity. Within 48 hours, Chase Bank was placed under receivership by the Central Bank. An investigation later showed it had adequate assets in the form of loans and investments, but it just couldn’t convert them to cash fast enough to pay everyone demanding their deposits back. As the receiver manager candidly told staff at the time, “When there is a run even in the biggest bank in the world, there is nothing that can be done because a bank actually survives on trust and confidence… the only way to stem a massive run is regulatory intervention. Otherwise today, we will wipe all the assets of the bank.” In other words, if everyone tries to cash out, the bank would have to liquidate (sell off) its loans and assets at fire-sale prices and still wouldn’t get enough cash quickly, leading to collapse. That’s exactly what happened to Chase.

The lesson? The money in your account is mostly an IOU from the bank, not bags of cash in a vault. In normal times, that IOU is as good as cash because you can use digital payments or make small withdrawals at will. But in a crisis of confidence, the illusion shatters. It’s like a crowded hall with a small exit – if a few people leave at a time, no problem. If everyone stampedes at once, disaster. Kenyan banks rely on the Central Bank as a backstop (lender of last resort) to provide emergency liquidity if needed, and deposit insurance (up to KSh 500,000 per depositor) to reassure the public. Still, no system can instantly redeem all IOUs for cash. That’s why maintaining trust is so crucial. This liquidity tightrope has become even more precarious in the digital age: rumors can spread on social media within minutes, and nowadays a panicked depositor doesn’t even need to line up at a branch – they can transfer money out to M-Pesa or another bank with a few taps. A digital bank run can unfold at the speed of a viral tweet.

3. The Illusion of “Available” Money

Perhaps the most thought-provoking risk Wanjiku discerned is what she called the “illusion of available cash.” This is the everyday mirage we all live in: seeing a number in our bank balance or M-Pesa wallet and treating it as if it’s definitively available, guaranteed. The truth is, it’s available only under normal conditions. The number is real, but it represents a claim on the bank or mobile provider, not actual cash in hand. If the systems that uphold those claims falter, we quickly realize how little of our money is tangible.

An illustration of this illusion occurred not long ago: in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Bank of Kenya temporarily lowered the required reserves ratio for banks (from 5.25% to 4.25%) to encourage banks to lend more and support the economy. This freed up billions of shillings of extra liquidity. Banks creating more money (by lending) was a strategy to soften the economic blow. It worked to some extent, but it also underscores how malleable the money supply is, and how it hinges on regulatory decisions and trust.

Another angle is the digital infrastructure: M-Pesa has had the occasional outage; banks sometimes have system downtimes. In those moments, people feel the vulnerability of not having physical cash. The illusion is that because you could withdraw your money or transact anytime, you don’t need to until you do – and if everyone tries at once, the system might seize up.

Wanjiku realized this doesn’t mean one should stuff cash in mattresses – rather, it’s a call for awareness. The money we use works because of collective belief and a delicate architecture of regulations, bank policies, and technology. When we all believe the money is real and will be honored, it functions smoothly as a medium of exchange. But it is indeed somewhat an illusion – a shared illusion that greases the wheels of commerce. Understanding that is part of financial literacy in the modern age.

Demystifying Money for a Smarter Future

By the end of her investigative journey, Wanjiku no longer viewed banks with blind mystique. She now saw a human-made system – ingenious, yes, but also imperfect – that turns our deposits into the lifeblood of the economy by creating new money through lending. This knowledge, she felt, is something every citizen deserves to have. In Kenya, where mobile money and digital loans have become part of daily life, public awareness is more important than ever. We cannot afford to treat money creation as a “trade secret” of bankers when it affects the price of unga (flour), the interest on our loans, and the stability of our jobs and savings.

There’s a Kenyan saying that “ujuzi ni nguvu” – knowledge is power. Demystifying how banks create money empowers people to make better decisions. For one, Wanjiku decided to be more cautious about digital borrowing. Knowing that these loans are literally at her fingertips, she set personal rules: for example, only use Fuliza for true emergencies and pay it back immediately, or avoid taking multiple app loans at once. She also started discussing with her friends about the interest rates and terms – pulling the curtain back on the “easy money” to reveal its true cost. If more borrowers do this, lenders will be pressured to be more transparent and fair, leading to a healthier credit culture.

On a systemic level, Wanjiku hopes for a more transparent financial system. When people understand that banks operate on trust and confidence, perhaps there will be less stigma in demanding accountability from financial institutions and regulators. It’s not “too complicated” for the public – as this story shows, anyone can grasp the basics. Banks, for their part, might benefit from educating their customers about how money and lending work, rather than relying on the old simplistic story of “we lend out your deposits” which isn’t the whole truth. In fact, being open about it can build trust – yes, your money isn’t all sitting in the vault, but here’s the prudence and safeguards we use to keep the system working.

The rise of mobile money in Kenya also presents an opportunity to build a more resilient system. With so much of our money digital, perhaps future innovations (like central bank digital currencies or improved deposit insurance schemes) could enhance stability. Imagine a system where even if a bank hiccups, people can seamlessly switch to another platform with their money, or where digital wallets have circuit breakers to prevent panics. These are conversations we can have once we shed the mystery and talk openly.

In the end, Wanjiku’s journey is one of empowerment. She started as a skeptic with a simple question and ended as an informed citizen who can see past the smoke and mirrors. Banks do create money – not by printing notes, but by expanding balances on a screen – and that money powers homes, businesses, and dreams across Kenya. It’s a powerful ability that must be wielded with wisdom. For us as the public, the goal is not to fear the system, but to understand it. With understanding, we can use financial tools more wisely (borrowing prudently, saving smartly) and also push for reforms that ensure the financial system remains a force for good.

Money might not grow on trees, but it does grow in bank ledgers and mobile phones. Now that the secret’s out, let’s cultivate that money tree responsibly – watering it with knowledge, pruning it with oversight, and sharing its fruit in a way that benefits all. After all, an informed Kenya is a stronger Kenya, financially and beyond. Ukweli usemwe – let the truth be told, so that the mystery of money is a mystery no more.

Sources:

- Bank of England, “Money creation in the modern economy,” Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q1.

- Samuel Marete, “The management of a nation’s money – Part I,” March 2024.

- Co-operative Bank of Kenya, Statement of Financial Position (June 30, 2022)

- The Star (Kenya), “Kenyans borrowed Sh2.3 billion daily on Fuliza in 2023,” May 2024.

- Sopra Steria SBS, Press Release on KCB M-Pesa loans, Feb 2023.

- Mashariki RPC, “Implications of Mobile Lending – Hidden Strain,” July 2025.

- The Star (Kenya), “Sh7.6bn Chase Bank panic withdrawals leads to its closure,” Jan 2019.