Pre-Colonial Period

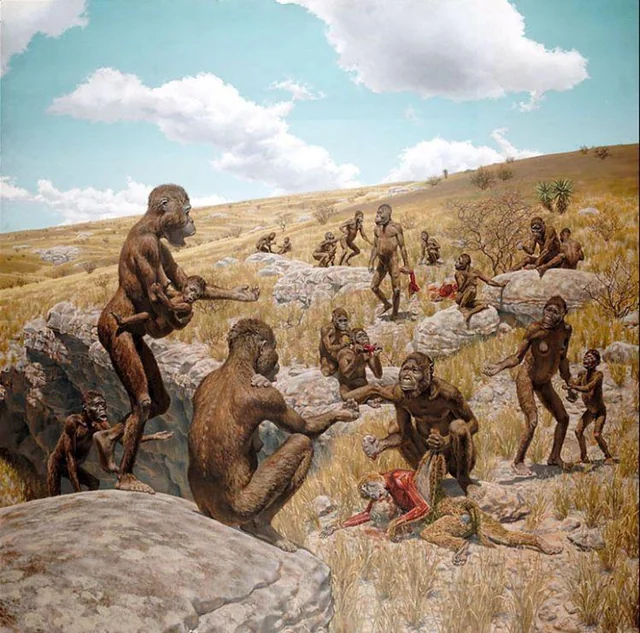

Prehistoric Times

Kenya’s designation as the “cradle of humanity” is rooted in its remarkable prehistoric discoveries, particularly in the Great Rift Valley, one of the world’s richest archaeological sites. Fossil evidence, such as Homo habilis (“handy man”) discovered at Olduvai Gorge and Homo erectus at Lake Turkana, demonstrates the early presence of human ancestors dating back over 2 million years. These hominins were among the first to use stone tools and adapt to diverse environments. The discoveries, made famous by the Leakey family and other paleoanthropologists, have provided invaluable insights into human evolution, including shifts in brain size, bipedalism, and social organization. Kenya’s prehistoric legacy underscores its critical role in humanity’s shared origins.

Migration of Bantu and Cushitic Peoples (circa 1000 BCE – 500 CE)

The migration of Bantu-speaking communities into Kenya was a significant development in East Africa’s cultural and demographic history. Originating from West Africa’s Niger-Congo basin, these groups journeyed across the continent over centuries, eventually settling in Kenya’s fertile highlands and Lake Victoria basin. They introduced agricultural practices, such as yam and millet cultivation, as well as iron smelting technology, which enabled the production of tools and weapons, giving them a competitive edge in expanding territories.

Simultaneously, Cushitic-speaking groups from the Horn of Africa moved into northern Kenya, bringing with them pastoralism and early forms of trade. These migrations catalyzed complex interethnic interactions, influencing languages, economies, and social systems. For instance, the blending of Bantu agriculturalists and Cushitic pastoralists created dynamic communities where subsistence strategies often complemented one another.

Additionally, these migrations shaped Kenya’s linguistic landscape. Today, many of Kenya’s ethnic groups, including the Kikuyu, Luhya, and Kamba, trace their linguistic and cultural roots to these Bantu migrations. Meanwhile, Cushitic-speaking groups such as the Somali and Borana left lasting marks on the region’s pastoral traditions.

Emergence of Swahili Culture (1st Millennium CE)

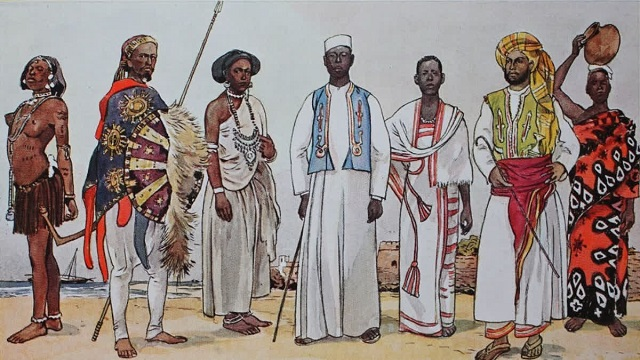

By the first millennium CE, Kenya’s coastal areas became integral to the thriving trade networks of the Indian Ocean. Local Bantu-speaking communities along the coast began interacting with Arab, Persian, Indian, and Southeast Asian traders. This exchange fostered the development of Swahili culture—a synthesis of African traditions and Islamic influences.

Swahili, derived from the Arabic word Sawahil (meaning “coasts”), became both a language and a cultural identity. The Swahili language incorporated extensive Arabic vocabulary while retaining a Bantu grammatical structure. The rise of coastal city-states such as Mombasa, Malindi, and Lamu further exemplified the prosperity of this trade era. These city-states were politically autonomous and economically vibrant, their wealth stemming from trade in gold, ivory, iron, and enslaved people. In return, they imported textiles, porcelain, spices, and other luxury goods.

Swahili culture was not limited to commerce; it also introduced Islamic religion and scholarship. Mosques, such as the ancient structures in Lamu, were built, and Islamic practices became integrated into the daily lives of many coastal inhabitants. Additionally, Swahili architecture, characterized by coral stone houses with intricately carved wooden doors, reflected both local ingenuity and external influences.

This cultural blend also extended to governance and art. Coastal elites adopted Islamic titles such as “Sultan” and aligned themselves with broader Islamic networks, further connecting Kenya’s coast to the Arabian Peninsula and beyond. Swahili poetry, such as the epic Utendi wa Tambuka (The Story of Tambuka), encapsulates this era’s intellectual and artistic richness.

By the end of the first millennium, the Swahili coast was a mosaic of interconnected communities. While deeply rooted in African traditions, it became a melting pot that linked Kenya to global networks, a legacy that still shapes the nation’s identity.

Colonial Period

Portuguese Arrival (1498)

The arrival of Vasco da Gama in 1498 marked a turning point in Kenya’s coastal history, initiating European involvement in the region. Da Gama’s expedition sought to establish a maritime route to India, making Kenya’s coastal city-states crucial for resupplying ships and facilitating trade. Recognizing the wealth of the Swahili city-states, particularly in commodities like ivory and gold, the Portuguese soon sought control over the region.

By 1505, under Francisco de Almeida, the Portuguese established a stronghold at Kilwa and later fortified Mombasa, asserting dominance over the Indian Ocean trade routes. Their rule, however, focused on economic exploitation rather than governance. They imposed heavy taxes and tribute on the Swahili city-states, disrupting local economies. Portuguese dominance provoked resistance, including notable uprisings in Mombasa and Pate.

The Portuguese were also pivotal in introducing Christianity to Kenya’s coast, establishing missions and churches. However, their influence waned by the late 17th century, as Omani Arabs, leveraging local discontent, expelled the Portuguese. The fall of Fort Jesus in 1698 marked the end of Portuguese rule and the beginning of Omani control over Kenya’s coast.

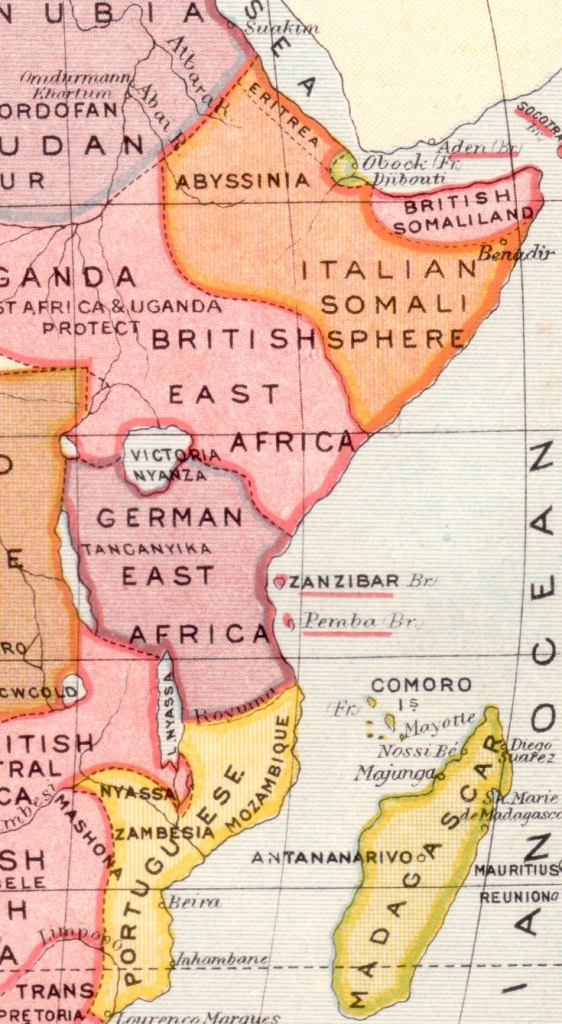

British East Africa Protectorate (1895)

The late 19th century saw Britain establish the East Africa Protectorate, formalized in 1895, bringing Kenya into the fold of British colonial ambitions. This period coincided with the “Scramble for Africa,” where European powers partitioned the continent. Britain viewed Kenya as a strategic location for securing the Nile Basin and as a corridor for connecting the Indian Ocean to Uganda’s fertile hinterlands.

A key project during this era was the construction of the Uganda Railway, which began in 1896. The railway linked Mombasa to Lake Victoria, enabling the transportation of goods and troops. Thousands of laborers, primarily from British India, were recruited for the arduous construction, giving rise to Kenya’s Indian community.

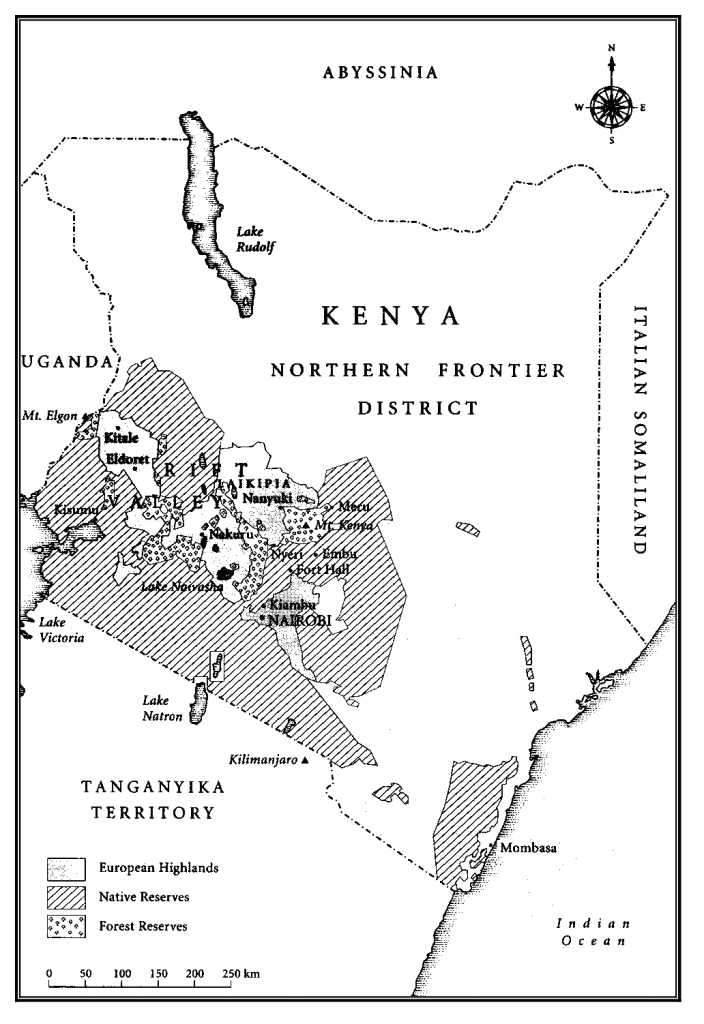

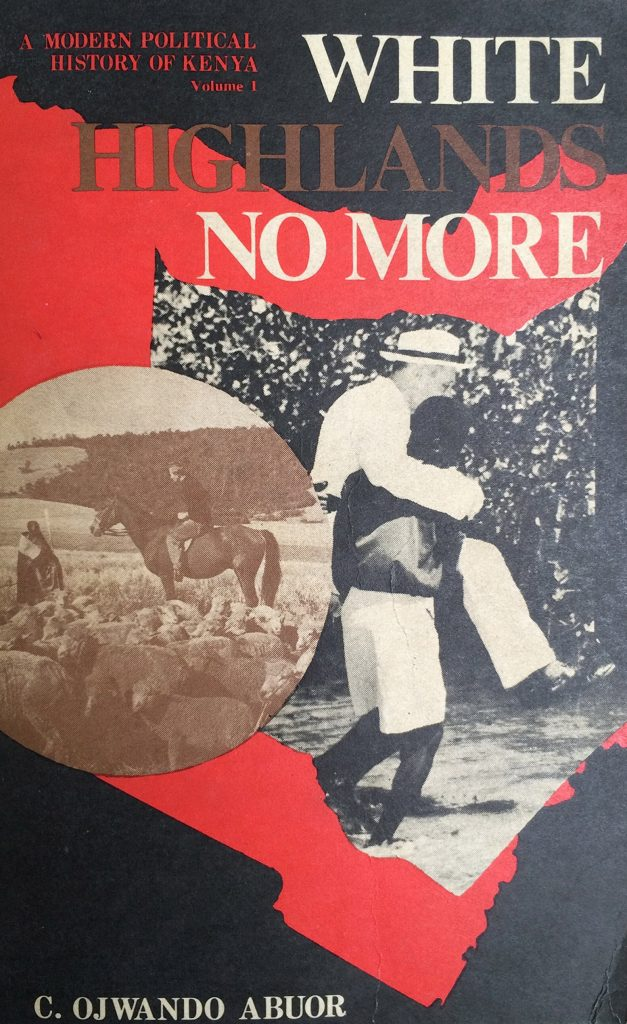

The railway facilitated the settlement of European settlers, who were allocated large tracts of fertile highlands, displacing local communities such as the Kikuyu and Maasai. Dubbed the “White Highlands,” this region became a cornerstone of the colonial economy, producing cash crops like tea, coffee, and pyrethrum.

Colonial administration during this time implemented systems of taxation and forced labor. The introduction of hut and poll taxes compelled Africans to enter wage labor on European farms and plantations, further entrenching inequalities. Resistance to these policies grew steadily.

Land Alienation and Resistance (Early 20th Century)

The early 20th century was characterized by increased land alienation and the marginalization of African communities. The colonial government confiscated vast tracts of land from indigenous groups, often relegating them to less arable “native reserves.” This dispossession disrupted traditional livelihoods, particularly among the Kikuyu, Kamba, and Maasai.

One of the earliest resistances to colonial policies was the Giriama Uprising (1913–1914). The Giriama people of the coastal hinterland rose against British impositions, including taxation and labor conscription. Led by cultural leaders such as Mekatilili wa Menza, the uprising symbolized the intersection of cultural preservation and anti-colonial sentiment. Although suppressed with considerable force, the Giriama Uprising highlighted the growing unrest among Kenyans.

Similarly, the rise of organizations like the East African Association (EAA) in the 1920s signified a shift towards organized political resistance. Led by figures such as Harry Thuku, the EAA protested land alienation, unfair taxes, and forced labor. Thuku’s arrest in 1922 sparked mass demonstrations in Nairobi, resulting in the deaths of several protestors.

The Mau Mau Rebellion (1952–1960)

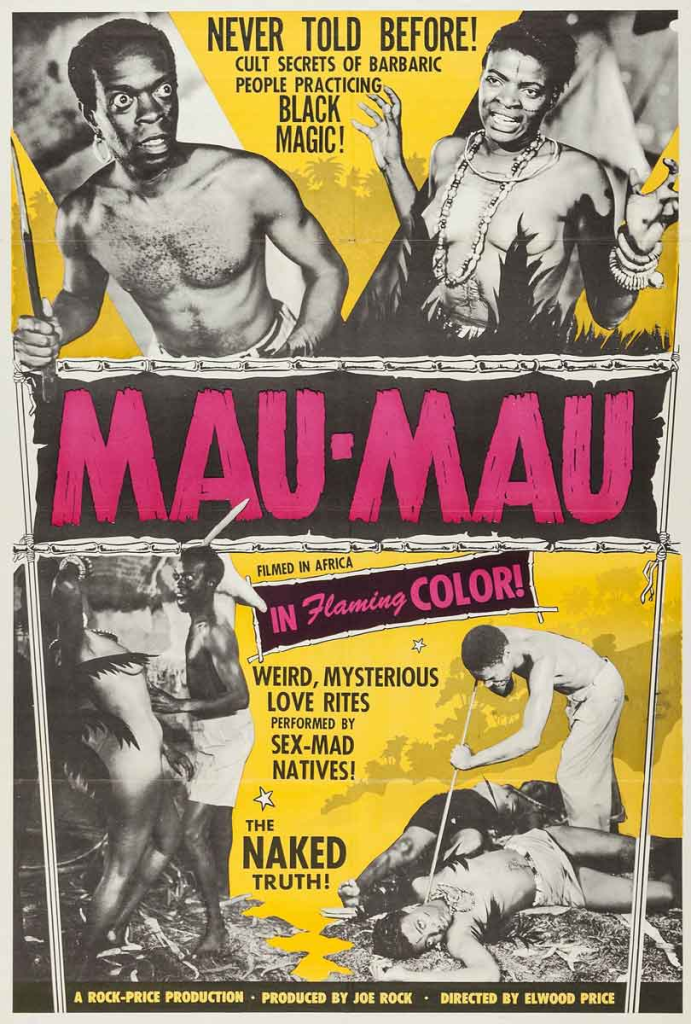

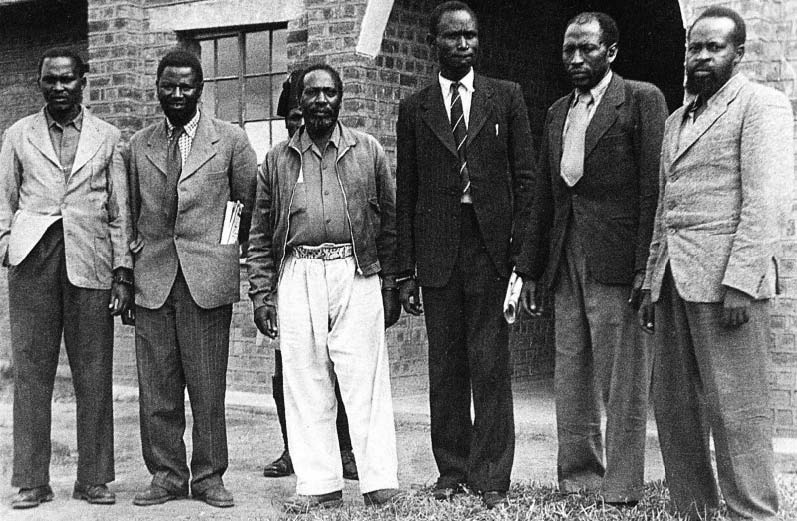

The Mau Mau rebellion was a watershed moment in Kenya’s colonial history. Emerging from deep-seated grievances over land, labor, and political marginalization, the movement was predominantly led by the Kikuyu, though many other communities also participated. The Mau Mau sought to reclaim stolen lands and end colonial rule, framing their struggle as both a political and cultural renaissance.

The rebellion began in earnest in the 1950s, with Mau Mau fighters adopting guerrilla tactics against British settlers and colonial forces. The forested Aberdare and Mount Kenya regions became key strongholds for Mau Mau fighters, who relied on the support of local communities for supplies and intelligence.

The British declared a state of emergency in 1952, deploying troops and employing draconian measures to suppress the rebellion. Over 1.5 million Kikuyu were forcibly relocated to “emergency villages,” where conditions were dire. The British also carried out mass detentions, often torturing suspected Mau Mau sympathizers.

Despite heavy losses, the Mau Mau rebellion had far-reaching impacts. It catalyzed international scrutiny of British colonial practices and inspired widespread calls for independence across Africa. The rebellion also unified diverse Kenyan communities in the struggle for freedom, laying the groundwork for the independence movement under Jomo Kenyatta and the Kenya African National Union (KANU).

Independence Era

Independence (1963)

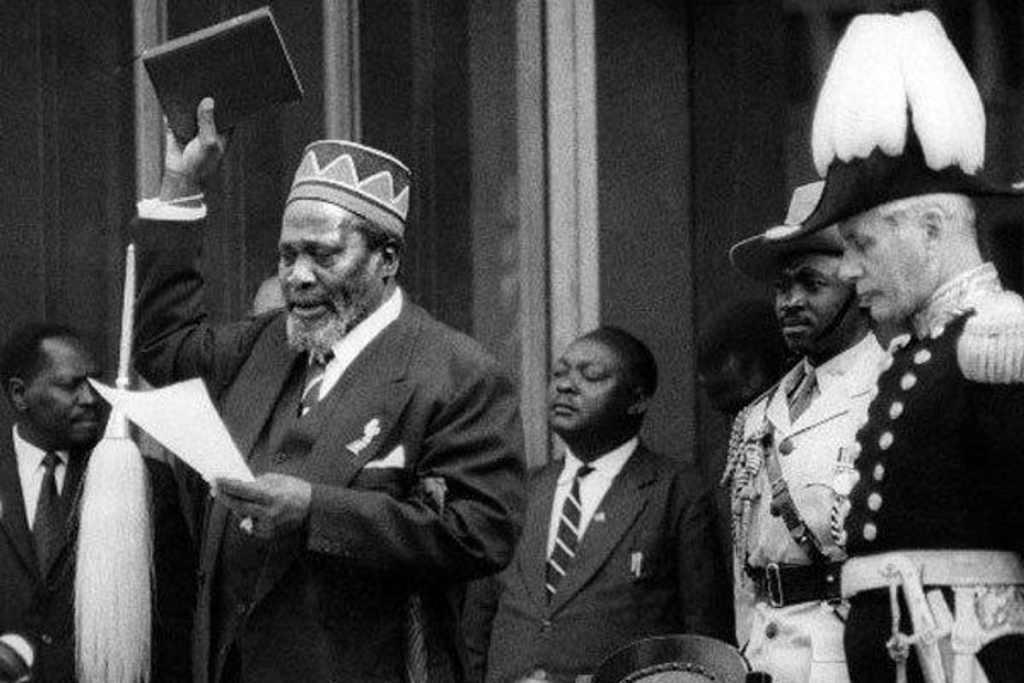

Kenya achieved independence from British colonial rule on December 12, 1963. This historic milestone followed years of anti-colonial struggles, including the Mau Mau rebellion and persistent political agitation by leaders like Jomo Kenyatta, Tom Mboya, and Oginga Odinga.

Kenya’s independence negotiations were concluded at the Lancaster House Conferences (1960–1963), where Kenyan leaders debated critical issues such as land redistribution, minority rights, and governance structures. The resulting constitutional framework established Kenya as a multi-party state, with the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) as the primary parties.

KANU, led by Jomo Kenyatta, emerged victorious in the pre-independence elections, securing a majority in the legislature. On Independence Day, Kenyatta became Kenya’s first Prime Minister, promising unity and progress under the slogan Harambee (“Pull together”). However, challenges loomed large, including addressing economic inequality, integrating diverse ethnic groups, and resolving disputes over land ownership.

Formation of a Republic (1964)

On December 12, 1964, Kenya transitioned from a dominion within the Commonwealth to a fully-fledged republic, one year after independence. Jomo Kenyatta became Kenya’s first President, with Oginga Odinga as the Vice President. This transformation symbolized the consolidation of power under a centralized government, a move that reflected Kenyatta’s vision of unity and strong leadership.

The transition was accompanied by amendments to the constitution, abolishing the ceremonial role of the Governor-General and centralizing executive power in the presidency. The Republic’s formation also marked Kenya’s departure from the multi-party politics envisioned at Lancaster House, as KANU increasingly marginalized opposition voices.

Post-Independence Politics (1964–1978)

Kenyatta’s Vision for Nation-Building

Kenyatta’s presidency focused on fostering national unity, economic development, and cultural pride. His administration prioritized:

- Economic Reconstruction: Policies emphasized modernizing agriculture, expanding education, and investing in infrastructure. Large-scale agricultural projects, such as the Million Acre Scheme, aimed to redistribute land to landless Kenyans.

- Harambee Philosophy: Kenyatta championed community self-help initiatives, encouraging collective efforts in building schools, clinics, and water projects.

Political Centralization

While Kenyatta’s early presidency promised inclusivity, it became increasingly characterized by political centralization and authoritarianism. KANU consolidated power by absorbing or suppressing opposition parties. KADU dissolved in 1964, and Kenya effectively became a one-party state.

Kenyatta relied on a close network of allies, predominantly from his Kikuyu ethnic group, leading to allegations of ethnic favoritism. The allocation of key government positions and land disproportionately favored Kikuyu elites, particularly in the Rift Valley and Central Province. This exacerbated ethnic tensions and marginalized other communities, such as the Luo, who had been pivotal in the independence struggle.

Ethnic and Political Tensions

Ethnic divisions came to a head in 1966, with the fallout between Kenyatta and Vice President Oginga Odinga. Odinga, disillusioned by the government’s neglect of socialist ideals and land redistribution, resigned and formed the Kenya People’s Union (KPU). The government responded by detaining KPU leaders and cracking down on opposition activities. The political rift signaled a broader marginalization of the Luo community in national politics.

The assassination of Tom Mboya in 1969 further fueled ethnic tensions. Mboya, a Luo and a charismatic KANU leader, was seen as a potential successor to Kenyatta. His death provoked unrest, particularly in Luo-dominated regions, and heightened perceptions of Kikuyu dominance in Kenyan politics.

Economic and Social Developments

Despite political challenges, Kenyatta’s presidency oversaw significant economic progress. GDP growth averaged around 6% annually during the 1960s and 1970s, driven by agricultural exports (coffee, tea, and horticulture) and foreign investment.

Education expanded rapidly under the Harambee system, with the establishment of numerous primary schools and teacher training colleges. However, economic policies favored large-scale farming and foreign investors, leaving small-scale farmers and pastoralist communities marginalized.

Foreign Policy

Kenyatta pursued a pragmatic foreign policy, positioning Kenya as a non-aligned state during the Cold War. While maintaining close ties with Britain and the United States, Kenya also engaged with other African nations through the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Regional cooperation was exemplified by Kenya’s participation in the East African Community (EAC), alongside Uganda and Tanzania.

End of Kenyatta Era (1978)

Kenyatta’s health began to decline in the mid-1970s, leading to increased political maneuvering among his inner circle. His death on August 22, 1978, marked the end of an era. Kenyatta left a mixed legacy: while credited with stabilizing Kenya and fostering economic growth, his presidency entrenched ethnic divisions and authoritarian governance. His successor, Daniel arap Moi, inherited a nation grappling with deep-seated inequalities and political centralization.

Era of Political Transition

Daniel arap Moi Presidency (1978–2002)

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi ascended to the presidency following the death of Jomo Kenyatta in 1978. Moi, a former teacher and Vice President, initially projected an image of humility and inclusiveness, encapsulated in his philosophy of Nyayo (footsteps), which emphasized peace, love, and unity. However, his 24-year presidency would become one of the most polarizing eras in Kenya’s history, marked by authoritarianism, economic turbulence, and moments of regional leadership.

Rise to Power and Consolidation of Authority

Moi’s early presidency was characterized by a careful balancing act to consolidate power in a political environment dominated by Kikuyu elites who had been entrenched during Kenyatta’s era. To solidify his position:

- Moi embarked on a “purge” of Kikuyu politicians perceived as threats, such as Charles Njonjo, a powerful former Attorney General and ally of Kenyatta. Njonjo’s dismissal in 1983 signaled Moi’s determination to break Kikuyu dominance and establish his own authority.

- In 1982, Moi moved to legally transform Kenya into a de jure one-party state by amending the constitution to make the Kenya African National Union (KANU) the sole political party. This followed a failed coup attempt by elements of the Kenya Air Force in August 1982, which further tightened his grip on power.

The coup attempt marked a turning point. Moi’s administration became increasingly repressive, using detention without trial, censorship, and state-controlled media to suppress dissent. The Special Branch, Kenya’s intelligence agency, was used extensively to monitor and silence opposition voices, fostering a climate of fear.

Economic Challenges and Structural Adjustments

Moi inherited an economy that had experienced robust growth during Kenyatta’s presidency. However, his tenure saw significant economic challenges:

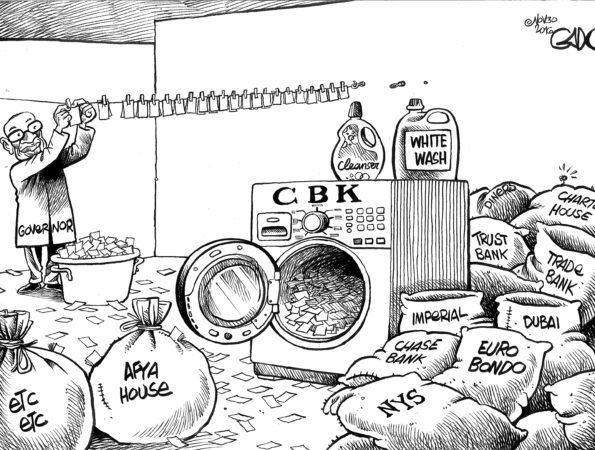

- Corruption and Mismanagement: The economy was severely undermined by systemic corruption. Public funds were embezzled at alarming rates, with scandals such as the Goldenberg affair (1990s), where billions of shillings were siphoned from the Central Bank of Kenya under the guise of export incentives, symbolizing the rot in public institutions.

- Decline in Agricultural Output: Agricultural productivity, the backbone of Kenya’s economy, stagnated due to mismanagement, lack of investment, and unfavorable global markets.

- Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs): Under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, Kenya implemented SAPs in the 1980s. These policies mandated privatization, reduced public spending, and liberalized markets, leading to widespread layoffs and a decline in public services, exacerbating poverty and inequality.

Repression and Human Rights Violations

Moi’s administration faced growing domestic and international criticism for its human rights abuses. Torture, arbitrary arrests, and the silencing of political opponents were widespread:

- The infamous Nyayo House Torture Chambers in Nairobi became a symbol of state repression, where suspected dissidents were detained and subjected to inhumane treatment.

- High-profile figures, such as former political detainees Kenneth Matiba, Raila Odinga, and Koigi wa Wamwere, emerged as symbols of resistance against Moi’s oppressive regime.

Regional Leadership and Peacekeeping

Amidst domestic challenges, Moi played a notable role in regional diplomacy. Kenya, under his leadership, became a hub for peace negotiations and conflict resolution in East Africa:

- Moi was instrumental in mediating peace processes in Sudan and Somalia, positioning Kenya as a stabilizing force in the region. Nairobi hosted several rounds of peace talks, which later contributed to the 2005 Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement.

- Moi’s administration maintained Kenya’s reputation as a haven for refugees, hosting displaced persons from Somalia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Sudan.

The Winds of Change

By the late 1980s, Moi’s presidency faced mounting pressure from both domestic civil society and the international community to democratize:

- Civil society organizations, such as the Green Belt Movement led by Wangari Maathai and human rights groups, intensified calls for political reforms.

- International donors linked aid to governance reforms, pressing Moi to embrace political pluralism.

Introduction of Multi-Party Democracy (1991)

The end of the Cold War marked a shift in global priorities, with Western nations emphasizing democracy and governance. In Kenya, this international pressure, combined with internal agitation, culminated in significant political reforms.

The Push for Reform

- Civil Society and Opposition Mobilization: By the early 1990s, a coalition of opposition leaders, church figures, and activists galvanized public sentiment against Moi’s one-party rule. Mass protests, such as the Saba Saba demonstrations on July 7, 1990, were met with brutal crackdowns but demonstrated the resilience of the pro-democracy movement.

- Donor Pressure: Foreign aid, critical to Kenya’s economy, was increasingly conditional on political reforms. The suspension of financial aid by the IMF and World Bank forced Moi to reconsider his stance on political pluralism.

Repeal of Section 2A and Multi-Party Politics

In December 1991, Moi reluctantly agreed to repeal Section 2A of the constitution, reintroducing multi-party democracy. This landmark decision allowed the registration of political parties, ending KANU’s monopoly. The move was met with widespread jubilation but also ushered in a period of political fragmentation and ethnic tensions.

Challenges of Transition

The transition to multi-party democracy was fraught with challenges:

- Ethnic Violence: The 1992 general elections, Kenya’s first multi-party polls in decades, were marred by ethnic violence, particularly in the Rift Valley. Allegations surfaced that state actors instigated violence to weaken opposition strongholds.

- Opposition Fragmentation: Despite the introduction of multi-party politics, opposition parties struggled to present a united front against Moi. KANU exploited divisions among the opposition to maintain its grip on power.

- Electoral Malpractice: Elections during this period were characterized by voter intimidation, ballot stuffing, and other forms of manipulation, raising questions about their credibility.

Modern Developments

Mwai Kibaki Presidency (2002–2013)

The election of Mwai Kibaki in December 2002 marked a watershed moment in Kenya’s history. Kibaki’s National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) swept to power with a landslide victory, ending nearly four decades of Kenya African National Union (KANU) dominance. Kibaki, a seasoned economist and former Vice President, campaigned on a platform of economic reform, anti-corruption, and constitutional change.

Economic Recovery and Infrastructure Development

Kibaki’s administration prioritized economic revival after years of stagnation under Daniel arap Moi. Major achievements included:

- Economic Growth: Kenya’s GDP growth improved significantly, averaging 4-7% annually by the mid-2000s. Reforms in fiscal management and a focus on private sector growth were instrumental.

- Free Primary Education: The introduction of free primary education in 2003 was a landmark policy that increased enrollment by over a million children, reflecting Kibaki’s commitment to social development.

- Infrastructure Development: Investments in infrastructure, particularly roads, energy, and telecommunications, transformed Kenya’s connectivity. Projects like the Thika Superhighway and rural electrification enhanced accessibility and economic activity.

Governance and Corruption Challenges

Despite economic gains, Kibaki’s administration faced criticism for failing to tackle corruption decisively. The Anglo-Leasing scandal, involving fraudulent contracts worth billions, tarnished his anti-corruption credentials. Critics argued that Kibaki’s inner circle, including powerful allies, benefited disproportionately from public resources.

Post-Election Violence (2007–2008)

Kibaki’s tenure was marred by the 2007–2008 post-election violence, one of Kenya’s darkest chapters:

- The disputed presidential election of December 2007, in which Kibaki was declared the winner against opposition leader Raila Odinga, triggered widespread unrest. Allegations of electoral fraud and vote manipulation fueled ethnic violence.

- Over 1,200 people were killed, and more than 600,000 were displaced in violence that highlighted deep-seated grievances over land, inequality, and political exclusion.

- The violence ended with a power-sharing agreement brokered by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, leading to the establishment of the Grand Coalition Government, with Kibaki as President and Odinga as Prime Minister.

New Constitution (2010)

One of Kibaki’s enduring legacies was the promulgation of Kenya’s new constitution on August 27, 2010, a milestone in the country’s democratic evolution. The new constitution was the culmination of decades of agitation for governance reforms.

Key Reforms

- Devolution of Power: The constitution created 47 county governments, devolving political and fiscal authority to local levels. This was intended to enhance service delivery, reduce inequality, and mitigate ethnic tensions by distributing power and resources more equitably.

- Judiciary and Electoral Reforms: It established an independent judiciary, including the Supreme Court, and revamped the electoral commission to ensure transparency and accountability.

- Bill of Rights: The constitution enshrined comprehensive protections for civil liberties, including economic, social, and cultural rights.

- Gender Equity: It introduced measures to ensure greater gender representation in governance, mandating that no more than two-thirds of elective and appointive positions be held by one gender.

The 2010 constitution was widely celebrated for its progressive provisions, but implementation faced significant challenges, including resistance from entrenched political elites.

Uhuru Kenyatta Presidency (2013–2022)

Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Kenya’s first President, assumed office in 2013 after defeating Raila Odinga in a tightly contested election. His presidency was characterized by ambitious infrastructure projects and a focus on economic growth but faced criticism for corruption and divisive politics.

Infrastructure Development

Kenyatta’s administration prioritized infrastructure under the Big Four Agenda:

- Standard Gauge Railway (SGR): The SGR, linking Mombasa to Nairobi and later to Naivasha, was the flagship project, reducing transport costs and boosting trade.

- Road and Port Expansion: Massive investments in roads, ports (e.g., Lamu Port), and energy (e.g., Lake Turkana Wind Power Project) aimed to transform Kenya into a regional economic hub.

Economic Growth and Challenges

- While Kenya maintained steady economic growth, averaging 5-6% annually, critics argued that the benefits were unevenly distributed.

- Rising public debt, fueled by large infrastructure loans, sparked concerns about fiscal sustainability. By the end of Kenyatta’s tenure, Kenya’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 65%, raising alarms over dependency on foreign creditors.

Corruption and Governance Issues

Kenyatta’s administration faced numerous corruption scandals, including the Arror and Kimwarer dams project and the National Youth Service (NYS) scandal. Efforts to combat corruption were perceived as insufficient, undermining public confidence.

Divisive Politics

The 2017 general elections, like in 2007, were marred by allegations of electoral fraud and protests. Kenyatta’s victory was initially nullified by the Supreme Court—the first such ruling in Africa—before he won the repeat election amid an opposition boycott. The period saw heightened ethnic polarization.

Building Bridges Initiative (BBI)

In 2018, Kenyatta and opposition leader Raila Odinga launched the BBI, aimed at promoting national unity and addressing structural governance issues. While controversial and ultimately unsuccessful after being struck down by the courts, the BBI underscored efforts to reconcile Kenya’s fractured political landscape.

William Ruto Presidency (2022–Present)

William Ruto, Kenyatta’s former deputy, won the 2022 presidential election under the Kenya Kwanza (Kenya First) coalition. His campaign focused on economic empowerment, promising to address inequality and unemployment under the bottom-up economic model. Turned out it was just for rhymes and poetry.

Early Priorities

- Economic Recovery: Ruto pledged to tackle Kenya’s high public debt and inflation. Initiatives included reducing the cost of living and supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

- Youth Employment: His administration has emphasized job creation, particularly for the youth, through Foreign Mboch forum led by Mutua.

- Social Welfare: Ruto’s government launched the Hustler Fund, providing affordable credit to informal sector workers and small business owners. However it has stalled with a majority defaulting

National Unity and Governance

Ruto’s presidency began with promises to heal divisions and strengthen national unity, though challenges remain, particularly in managing corruption and favorism among the sugoi loyalists.

Cultural and Social Milestones

Women in Politics and Leadership

Historical Foundations: Mekatilili wa Menza

The history of women’s participation in Kenya’s socio-political sphere can be traced back to influential figures such as Mekatilili wa Menza, a Giriama leader who spearheaded resistance against British colonial rule in 1913. Mekatilili mobilized her community against colonial impositions like forced labor and taxation, emphasizing cultural pride and self-determination. Her leadership was rooted in traditional Giriama customs, which she utilized to galvanize support, including organizing women’s groups and invoking spiritual authority. Despite her eventual arrest and exile, Mekatilili’s legacy as a trailblazer for women’s resistance remains iconic in Kenyan history.

The Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation (MYWO)

Founded in 1952, MYWO emerged as a grassroots women’s movement aimed at addressing welfare and empowerment during Kenya’s transition to independence. Initially focused on rural women’s development, MYWO became a platform for advocating women’s rights in governance. By the 1980s and 1990s, the organization transformed into a significant political force, lobbying for gender equality in policy-making and electoral representation. MYWO’s efforts played a crucial role in ensuring gender-sensitive provisions were included in Kenya’s 2010 constitution, such as the requirement for no more than two-thirds of elected or appointed officials to be of one gender.

Modern Contributions

The prominence of women in leadership has grown steadily. Leaders like Martha Karua, Kenya’s former Minister of Justice, and women governors and legislators reflect the strides women have made in the political arena. While challenges persist, the representation of women has fostered greater inclusivity and diverse perspectives in Kenyan politics.

Environmental Conservation

Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt Movement

Wangari Maathai, Africa’s first female Nobel Peace Prize laureate (2004), profoundly transformed Kenya’s approach to environmental conservation and social justice. In 1977, she founded the Green Belt Movement, an environmental organization that combined grassroots tree-planting campaigns with advocacy for democracy, women’s rights, and sustainable development.

The movement’s achievements include:

- Tree-Planting Initiatives: Over 51 million trees have been planted in Kenya to combat deforestation, restore ecosystems, and empower local communities, particularly women.

- Community Empowerment: Maathai’s initiatives trained rural women in environmental stewardship, linking ecological conservation with economic benefits.

- Advocacy and Resistance: The Green Belt Movement often stood against environmentally destructive policies. Notably, Maathai opposed the construction of a high-rise in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park and the grabbing of Karura Forest for private development, enduring physical threats and public criticism in her fight for conservation.

Impact on Policy and Global Recognition

Wangari Maathai’s work inspired a global discourse on the interconnectedness of environmental sustainability, gender equality, and governance. Her legacy continues to influence Kenya’s environmental policies and grassroots activism, making Kenya a model for integrating ecological and social justice.