Cyrus Shakhalaga Khwa Jirongo burst onto Kenya’s national stage in 1992 as a brash young political operator leading the Youth for KANU ’92 (YK’92) lobby group. The country was undergoing a historic transition – President Daniel arap Moi had reluctantly allowed multiparty politics, and an energized opposition was rallying to unseat him. In response, Moi’s ruling party banked on YK’92, a state-sanctioned youth brigade chaired by Jirongo, to secure his re-election in Kenya’s first competitive polls since 1966. Under Jirongo’s leadership, YK’92 became synonymous with aggressive grassroots mobilization and unprecedented campaign financing. The group fanned out across the country, wooing youth with slick propaganda and fistfuls of cash in a high-octane bid to keep KANU in power.

Rise Through YK’92 – Kingmaker in Kenya’s First Multiparty Election

Backed by powerful patrons in Moi’s inner circle, YK’92 operated with seemingly bottomless resources. So flush was their campaign that in the midst of sky-high inflation, Kenya’s Central Bank introduced a new 500 shilling note – and ordinary Kenyans wryly nicknamed it the “Jirongo” after the man throwing the currency around. Sh500 Jirongo notes greased the machinery of patronage. Jirongo and his lieutenants (including a young William Ruto as YK’92 treasurer) handed out cash at rallies and youth events, cultivating an image of swaggering wealth in service of political ends. This infusion of money was not entirely benign – critics alleged it stemmed from dubious sources, notably the infamous Goldenberg scandal that siphoned public funds. Jirongo later admitted that YK’92’s war chest was “obviously…Goldenberg money,” acknowledging that an elaborate gold export kickback scheme injected an estimated Sh11 billion into KANU’s 1992 campaign kitty. In essence, state coffers and corruption proceeds became the lifeblood of YK’92’s electioneering, enabling Jirongo’s operation to outspend and outmaneuver the nascent opposition.

Strategically, Jirongo proved adept at blending patronage with populism. YK’92 didn’t just buy support; it energized youth participation on a scale Kenya hadn’t seen. Jirongo’s team was loud, confident, and everywhere – their rallies blasting pro-Moi slogans, their convoys of luxury vehicles rolling into remote villages with cash and campaign swag. The youthful flair masked a ruthless efficiency: by funneling cash to grassroots networks, YK’92 under Jirongo helped fracture the opposition vote and secure Moi’s narrow victory in the 1992 election . Jirongo emerged from that campaign as a celebrated KANU kingmaker, his name quite literally imprinted on Kenyan currency and political lore. At just 31 years old, he had become, in the eyes of many, the face of KANU’s survival – a mix of master strategist and cash-slinging “godfather” of youth politics.

Yet the YK’92 triumph was double-edged. It won the election but left a trail of economic wreckage and controversy that would soon shadow Jirongo’s reputation. The overzealous money printing (and the Goldenberg-fueled inflation) ravaged Kenya’s economy, and many pointed fingers at YK’92’s spending spree for devaluing the shilling. Almost overnight, Jirongo’s name became a byword for excess – he was the “cash czar” of an era of patronage. Still, in the immediate aftermath, his star was rising: he transitioned from campaign operative to elected office, riding the momentum of YK’92 into Parliament in the 1997 elections. The very skills that made him formidable – mobilizing patronage and commanding loyalty – now positioned him as a newcomer to watch in Kenya’s legislature.

Patron to Pariah – The Moi Alliance and Its Bitter Fallout

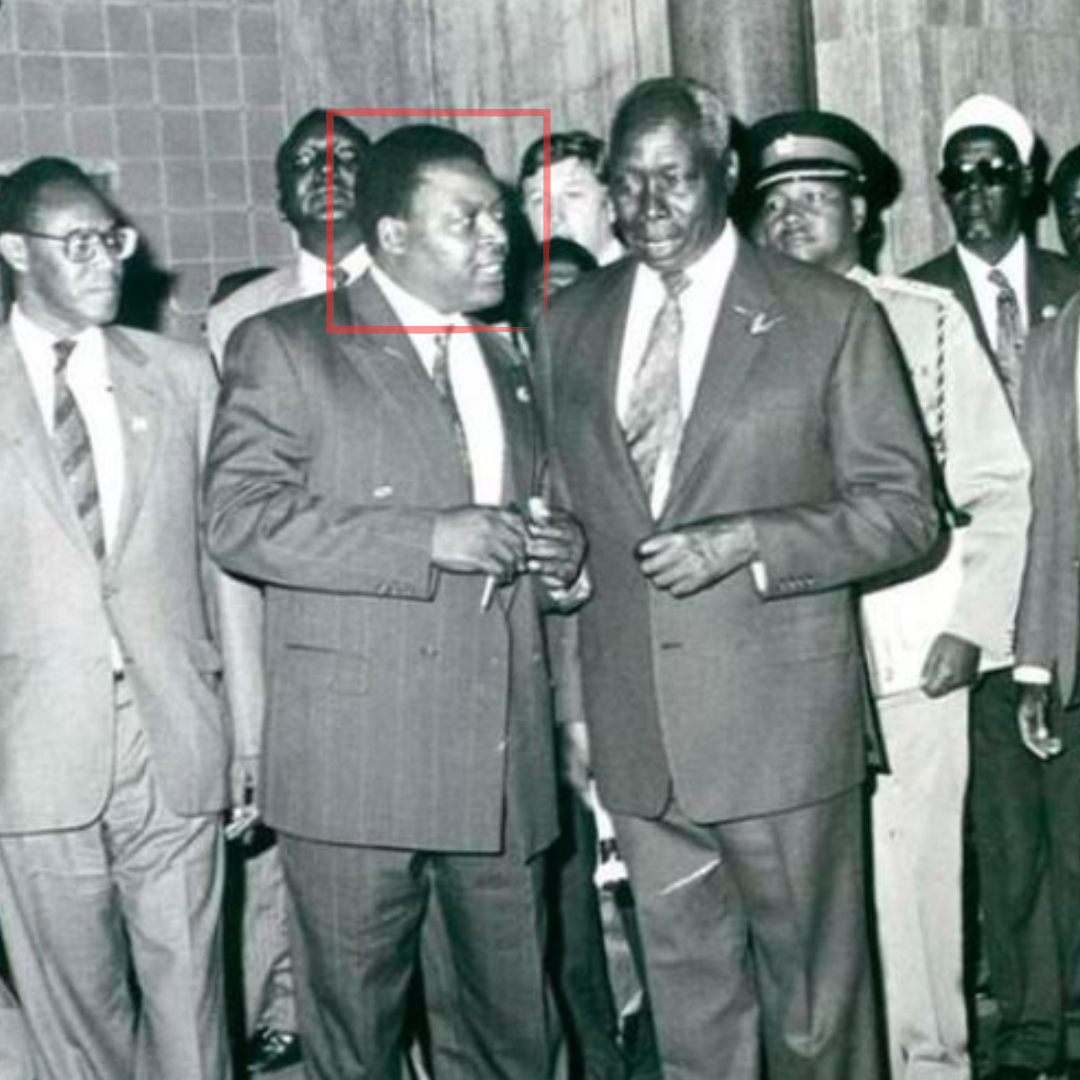

Jirongo’s early ascent owed much to his close but complex relationship with President Moi. In the 1990s, Moi viewed Jirongo as a useful protégé, an energetic point-man to court the youth and counter opposition firebrands. With Moi’s patronage, Jirongo enjoyed extraordinary latitude – a “special status” that made him virtually untouchable at the height of YK’92’s powers. He could pull off audacious deals and command state resources that even senior politicians envied. This earned him prestige, but also quiet resentment from the KANU old guard who saw the young upstart accumulating influence (and wealth) at breakneck speed.

By 1997, Jirongo had leveraged Moi’s backing to win the Lugari Constituency parliamentary seat on a KANU ticket. He was rewarded further in March 2002, when Moi appointed him Minister for Rural Development, a cabinet post that signaled Jirongo’s place in the president’s inner circle. At that juncture, Moi was preparing to exit after 24 years in power, and he tapped loyalists like Jirongo to shore up support in KANU’s final stretch. Publicly, Jirongo remained a staunch Moi ally, defending the regime’s record and pushing the party line. Privately, however, cracks were forming in their alliance – cracks born of ambition, distrust, and the shifting winds of succession politics.

The bond between mentor and protégé began to splinter in the late 1990s. Having tasted power and immense wealth, Jirongo grew more assertive and politically independent, which did not sit well with Moi’s famously firm grip on KANU. Around 1999, only two years into his MP tenure, Jirongo fell out with the ruling party’s hierarchy. He was linked to an attempt at a new political vehicle – the United Democratic Movement (UDM) – a clear sign that he was positioning himself outside Moi’s direct control. This move infuriated the KANU establishment. Moi, ever the shrewd political operator, likely interpreted Jirongo’s UDM foray as disloyalty and a threat to party unity. The once-favored son was now seen as veering off-script, influenced perhaps by other dissenting voices or his own aspirations beyond being Moi’s aide-de-camp.

Moi’s response was to clip Jirongo’s wings. Throughout KANU’s history, those perceived as too independent or ambitious often found themselves isolated – and Jirongo was no exception. He lost favor as Moi increasingly leaned on other lieutenants and groomed new protégés (most notably a young Uhuru Kenyatta) for leadership. By the pivotal 2002 elections, KANU was fracturing: a segment of younger politicians and Moi’s longtime allies (the Rainbow Alliance, which evolved into the opposition Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)) openly rebelled against Moi’s succession plan. Jirongo’s position during this turbulence was awkward. He was neither fully inside Moi’s kitchen cabinet nor embraced by the reformist rebels. He had earlier signaled dissent, yet ultimately he stuck with KANU in 2002 – perhaps hedging his bets or lacking a solid alliance with the LDP camp. He contested his Lugari seat on a KANU ticket even as the party imploded, and suffered a stinging defeat to a NARC candidate amid the nationwide wave against Moi’s cronies.

That loss marked the definitive break between Jirongo and Moi. KANU was out of power, Moi was retiring, and Jirongo was suddenly a man without a patron. The relationship that had vaulted him to prominence was effectively over – not with a dramatic public clash, but with a quiet parting of ways. Moi’s final act of goodwill had been the short-lived ministerial appointment in 2002, widely seen as an attempt to appease restive Western Kenya leaders like Jirongo in the face of KANU’s crisis. When that gambit failed and KANU lost, Jirongo was left politically adrift. The once dutiful protégé had already angered the old guard, and with Moi’s exit, he lost the protective shield of presidential favor.

In the years after, Jirongo did not shy from critiquing his former benefactors. He spoke openly about KANU-era scandals (even implicating the regime in Goldenberg), as if casting himself as a truth-teller about the very system that nurtured him. Some saw this as sour grapes or reinvention; others thought Jirongo was trying to cleanse his legacy by coming clean. Either way, the Moi-Jirongo alliance had come full circle – from warm camaraderie in YK’92’s heyday to an estranged distance. The break was sealed by history: when Moi handpicked successors who weren’t Jirongo, Jirongo chose to walk his own path, for better or worse. In the end, the man who once sat at Moi’s right hand would find himself on the outside looking in, navigating a new political landscape without the old anchor of patronage.

Business Empire Built on Sand – Deals, Dollars and Early Wealth

Parallel to his political rise, Jirongo cultivated the image of a businessman with a Midas touch. By his mid-30s, he was rumoured to be a billionaire in Kenyan shillings, flush with assets across Nairobi and his native Western Province. The truth behind that wealth is a story of bold enterprise entangled with crony capitalism. Jirongo’s early capital accumulation was turbocharged by his political connections in the 1990s. As YK’92 chair, he enjoyed privileged access to state resources and bank credit that ordinary Kenyans could only dream of. He parlayed those connections into lucrative ventures – especially in real estate, finance and trading deals that thrived on government largesse.

One notorious saga stands out: Jirongo’s companies took massive loans from a state-owned lender, Postbank Credit Ltd, in the early ’90s, only to default spectacularly. In 1993, while Kenya was reeling from a fiscal deficit of KSh2.7 billion, Jirongo secured loans of a similar magnitude from Postbank, using huge tracts of land as collateral. His firm Offshore Trading Company borrowed KSh1.1 billion backed by a 1,000-acre plot in Nairobi’s Ruai area. Another of his outfits, Sololo Outlets, took KSh1.65 billion against a title for 2.5 acres in Nairobi’s industrial zone. These were astronomical sums at the time – nearly the size of Kenya’s budget shortfall – yet Jirongo obtained them with ease, a testament to the “anything goes” climate of the Moi era.

The deals were as dubious as they were ambitious. It later emerged that the land put up as security belonged to the government, meaning the bank had no recourse when Jirongo’s companies defaulted. Postbank Credit collapsed under the weight of bad debts, with Jirongo’s unpaid loans a prime factor in its downfall. By one estimate, Jirongo’s unpaid loans plus interest ballooned to KSh40 billion owed to the Kenyan taxpayer – a staggering legacy of the 90s banking crisis. This was not an isolated incident, but emblematic of how Jirongo built his empire: high-stakes ventures protected by political influence. Whether it was acquiring public land on the cheap, flipping properties to state agencies at inflated prices, or getting insider access to credit, Jirongo exemplified the “get-rich-quick” ethos that many politically connected businessmen of that era followed.

Indeed, Jirongo’s name surfaced in multiple scandals. In the NSSF Hazina Estate project, his company Sololo Outlets struck a deal to sell housing units to the National Social Security Fund for over KSh1.2 billion; when financing snags occurred, a trail of disputes and lawsuits followed, again involving Postbank and other intermediaries. Public institutions repeatedly found themselves entangled with Jirongo’s ventures – and often on the losing end. At the height of his powers in the mid-90s, he was said to almost single-handedly cause the collapse of Postbank Credit, and by extension, he contributed to a broader banking sector meltdown that saw over a dozen banks fail. Yet, tellingly, Jirongo himself emerged unscathed in the short term: the banks folded, but he kept the money. He was rarely held to account in that era of weak institutions. This only fed the legend of his untouchability – the idea that Jirongo could bend rules and prosper where others faltered.

Outside finance, Jirongo dabbled in diverse sectors. He had interests in construction, agriculture, and even sports (notably serving as chairman of the AFC Leopards football club in 1991, which boosted his public profile). He cultivated an image of a development mogul, often boasting about farming projects or real estate developments he led to “transform our communities.” However, whispers persisted that many of these projects were fronts to siphon public funds or leverage political patronage for profit. Jirongo’s defenders argue that he also created jobs and invested in the economy, pointing to properties and businesses he set up during his heyday. But even admirers cannot ignore that his fortune was intertwined with his politics – without Moi’s system shielding him, Jirongo’s business empire might have looked very different.

By the 2000s, as reform and anti-corruption scrutiny grew, the foundations of Jirongo’s empire began to tremble. Some deals unraveled, court battles over debts mounted, and the once free-flowing credit dried up. What remained undeniable is that Jirongo’s early business success was built on shaky ground – quicksand comprised of easy loans, insider contracts and public money. It was a classic tale in Kenyan politics: patronage breeds wealth, which in turn fuels more patronage. Jirongo perfected this cycle in the ’90s, emerging as both a political kingmaker and a fabulously wealthy man. The question that would haunt him later was whether that empire could withstand scrutiny and survive outside the corridors of power that created it.

Realignments in a New Dawn – From KANU’s Fall to Independent Paths

The 2002 election was a watershed for Kenya – KANU was swept from power by the opposition NARC coalition – and it forced Jirongo into a period of political realignment and soul-searching. Having been a consummate KANU insider, he suddenly found himself on the outside of the new Kibaki government, and even out of Parliament after his electoral loss. Like many KANU stalwarts licking their wounds, Jirongo had to decide: would he retreat, reinvent, or resist? Characteristically, he chose reinvention, charting an independent path that often put him at odds with both his former allies and the new establishment.

In the immediate post-2002 period, Jirongo maintained a low profile but worked behind the scenes to craft a comeback. He flirted with joining the band of KANU breakaways who had formed the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) under Raila Odinga’s leadership. While not formally in LDP, he shared common cause with these rebels who opposed Moi’s succession plan. Jirongo’s attempt in 2003 to register the United Democratic Movement (UDM) – which echoed the Rainbow Alliance spirit – indicated his desire to be part of the new opposition nucleus against President Kibaki’s government. However, internal politics and perhaps lingering distrust kept him from fully integrating into Raila’s circle at that time. Instead, Jirongo blazed his own trail by founding a new outfit, the Kenya African Democratic Development Union (KADDU). This move was quintessential Jirongo: rather than play second fiddle in someone else’s party, he would revive his clout through a personal political vehicle.

The gamble paid off, at least initially. In the 2007 elections, Jirongo made a triumphant return to Parliament, recapturing his Lugari seat under the KADDU banner. It was no small feat – 2007 was a highly polarized contest between Raila’s ODM and Kibaki’s PNU, leaving little room for outsiders. Yet Jirongo managed to win as essentially a one-man party. KADDU earned only that single parliamentary seat nationwide, making Jirongo the sole standard-bearer. This left him in an unusual position: he was back in the game, but without a larger team or coalition. When a negotiated Grand Coalition government was formed in 2008 to quell post-election violence, every significant party was invited to the table except KADDU. Jirongo thus found himself as a lonely opposition voice – what the press dubbed a “one-man opposition” in the 10th Parliament. While this isolation limited his influence on national policy, it also burnished a renegade aura around Jirongo. He styled himself as an independent watchdog, free to criticize both government and the ODM wing of the coalition since he owed allegiance to neither. For a politician long seen as a system insider, this outsider stance was a novel turn.

As the 2013 election approached, Jirongo once again recalibrated. Sensing that KADDU’s vehicle was too small for a presidential run, he dissolved it and briefly aligned with newer alliances. He was associated at different points with Deputy Prime Minister Musalia Mudavadi’s circle and even flirted with William Ruto’s URP, but ultimately went his own way. Jirongo declared his candidacy for President in 2013, running on a ticket of clean governance and youth empowerment – an irony not lost on observers, given his YK’92 past. However, the realities of Kenyan coalition politics forced a course change. As Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto united their forces (Jubilee) and Raila Odinga led the CORD coalition, Jirongo lacked the national machinery to compete. He tactically withdrew from the presidential race and instead vied for the newly created Kakamega County Senate seat, throwing his support behind Raila Odinga for the presidency. In essence, Jirongo aligned with Raila’s side in 2013, coming full circle to cooperate with the very opposition figures he once battled in the 90s. His Senate bid fell short – he lost to the incumbent firebrand Dr. Boni Khalwale – but the realignment cemented Jirongo’s role as a regional powerbroker rather than a national contender.

Undeterred, he kept his political vehicle in motion. Ahead of the 2017 elections, Jirongo rebranded under the United Democratic Party (UDP) and yet again announced a run for the presidency. By this time, he was a veteran on the fringes: respected for his past, but not seen as a future president by the wider public. The 2017 race was essentially a two-horse duel between Uhuru and Raila; Jirongo’s candidacy was quixotic, if not symbolic. He campaigned on an anti-corruption platform – highlighting institutional reforms and claiming he could speak truths others wouldn’t. When the votes came in, he managed roughly 11,000 votes (about 0.07% of the total), a humbling outcome that nonetheless he took in stride as “laying groundwork for Kenya’s political renewal”. Many saw it as the twilight of his national ambitions.

By the 2022 election cycle, Jirongo embraced coalition politics fully. His UDP joined Raila Odinga’s grand Azimio la Umoja coalition, aligning with mainstream opposition in a bid to stay relevantt. Jirongo himself shifted focus to county politics, contesting the Kakamega gubernatorial seat in 2022 under Azimio’s umbrella. It was another tough race in a region where former allies turned competitors. He ultimately lost to the ODM candidate (Fernandes Barasa), marking yet another electoral defeat. However, Jirongo’s ability to continually reinvent his alignments was on display: from KANU to independent, to opposition alliance and back again. His post-2002 journey highlights the fluid nature of Kenyan politics, where former enemies become allies and vice versa. Through it all, Jirongo portrayed himself as an issue-based politician rather than a tribal chieftain – a stance that won him respect in some quarters but left him without a solid ethnic voting bloc to rely on.

In summary, the two decades after KANU’s fall saw Jirongo morph from a ruling party heavyweight to an independent operator perpetually seeking a way back to the center of power. He tasted brief success (as in 2007) and frequent disappointments, but he never stopped maneuvering. To his credit, he remained ideologically malleable yet consistent in one aspect: his refusal to be anyone’s lieutenant for long. If he couldn’t sit on the throne, he preferred to chart his own course rather than be a courtier in another king’s court – a trait that defined his realignments for better or worse.

In the Arena – Electoral Pursuits in 2007, 2013, and 2017

Jirongo’s post-Moi political career was characterized by repeated quests for elective office – each campaign reflecting shifting strategies and mounting challenges. His major electoral pursuits and outcomes include:

- 2007: Running under his own KADDU party, Jirongo focused on reclaiming a parliamentary seat rather than chasing the presidency. He won the Lugari MP seat, capitalizing on local support even as larger parties dominated nationally. His platform was regionally tailored – emphasizing development in Western Kenya and casting himself as an independent voice unaligned to either Kibaki’s or Raila’s camps. The challenge was isolation: as KADDU’s sole MP, Jirongo had little leverage in the hung Parliament that followed. He used his position to critique both sides of the Grand Coalition, but without a bloc behind him, his influence remained limited to rhetoric.

- 2013: Initially, Jirongo aimed for the presidency, launching a campaign that highlighted corruption issues and the need for generational change. He presented himself as having the insider knowledge to fight graft (famously quipping that “it takes a thief to catch a thief” – acknowledging his past to bolster his anti-corruption cred). However, facing the juggernauts of Uhuru/Ruto and Raila/Kalonzo alliances, he recalibrated. Jirongo stepped down to contest the Kakamega Senate, aligning with Raila’s CORD coalition by endorsing Raila for president. Despite this alliance, he lost the Senate race to Boni Khalwale, a seasoned local rival, exposing Jirongo’s struggle to command votes even in his home turf when up against entrenched competitors. The 2013 campaign’s challenge was relevance – Jirongo had to fight perceptions that he was a relic of the 90s in a new constitutional era, and the electorate largely gravitated to fresher or better-organized faces.

- 2017: Undeterred by past setbacks, Jirongo returned to the presidential ballot under the UDP banner. His platform was strikingly idealistic: he spoke of restoring integrity, empowering youth, and championing the downtrodden. He also did not mince words about his former YK’92 colleague William Ruto, casting doubt on Ruto’s record and character in what came off as both a policy critique and personal vendetta. The campaign, however, barely registered nationally. Jirongo lacked the funds and grassroots machinery of his earlier days – a far cry from when he could scatter “Jirongo notes” from helicopters. Moreover, 2017’s highly charged duel between Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga left scant room for minor candidates. Jirongo garnered around 11,000 votes (0.07%), finishing as an extreme long-shot candidate. A major challenge he faced this time was legal and financial. Mid-campaign, a court declared him bankrupt over a KSh700 million debt, theoretically disqualifying him from the race. He managed to get a temporary reprieve from the bankruptcy order to stay on the ballot, but the episode underlined how severely his fortunes had changed. The one-time tycoon was now struggling to finance a campaign and battling creditors in court, which undoubtedly hampered his credibility in voters’ eyes.

Across these electoral endeavors, certain themes persist. Jirongo often cast himself as the voice of the forgotten – railing against what he saw as the indecency and craftiness of mainstream politicians, calling out corruption in both government and opposition. He tried to sell experience as his asset (“I know where the bodies are buried,” he would imply, referencing insider knowledge). But the flip side of experience was baggage: many Kenyans could not dissociate him from the very corrupt old order he decried. Moreover, Jirongo’s campaigns lacked a clear constituency. Unlike other leaders from Western Kenya who cultivated ethnic or regional bases, Jirongo’s support was fragmented – he was respected by some for his past prowess, but he did not galvanize a loyal voter bloc.

Ultimately, Jirongo’s electoral track record post-2002 is one of diminishing returns. Each successive race saw him earn fewer votes and face tougher odds. Yet, it is also a testimony to his determination (or arguably, stubbornness) that he kept vying for high office well into his 50s and 60s, refusing to fade quietly into retirement. In his mind, each election was a chance for vindication – an opportunity to prove that the loud operator of YK’92 could reinvent himself as a reformist elder statesman. The reality, however, was that the ground had shifted beneath his feet, and Cyrus Jirongo would remain a perennial also-ran in the new era of Kenyan politics.

Public Perception – Flamboyant Operator, Powerbroker, or Truth-Teller?

Throughout his career, Cyrus Jirongo elicited strong and polarized reactions from the public. In the early days, he was seen as the personification of money and power in politics. His very surname entered slang; calling a 500-shilling note “a Jirongo” spoke volumes about how Kenyans viewed him – the man who would literally hand you cash for support. This image of flamboyance and opulence was reinforced by his lifestyle: motorcades of flashy cars, a coterie of hangers-on, and rumours of lavish spending in nightclubs and at political events. Jirongo embraced the big-man persona with relish. He cut the figure of a brash young tycoon, dressing sharply and talking tough. Many youth in the 90s admired him – here was a hustler who had made it big, an inspiration that one of their own could dine with presidents (quite literally, as he was often by Moi’s side). His supporters dubbed him “Shakad” (from his middle name Shakhalaga) and saw in him a patron who could uplift them. Detractors, however, used less flattering labels, calling him “Mr. Moneybags” or a KANU project, implying his success was built on ill-gotten wealth and favoritism rather than merit.

As time went on, another aspect of Jirongo’s public perception emerged: that of a political wheeler-dealer who was loud and unabashed in pursuit of his interests. He was, in Kenyan parlance, “noisy” – often washing dirty linen in public. For instance, he did not hesitate to expose uncomfortable secrets about fellow politicians. Over the years, Jirongo openly accused figures like William Ruto of betraying original ideals and indulging in graft, essentially painting others as apprentices who learned corruption from his generation. These episodes earned him a somewhat marginalized truth-teller image. There was a sense that when Jirongo spoke, he might be doing so out of bitterness at being sidelined, but he also might just air truths others feared to admit. A section of the public grew to appreciate this blunt candor. They saw Jirongo as a man who had nothing left to lose and would call a spade a spade – whether talking about the Goldenberg saga or the underhand dealings in Jubilee government, he was often brutally frank. For a political class known for doublespeak, Jirongo’s occasional outbursts of honesty were refreshing, albeit viewed with skepticism given his own past.

Meanwhile, his reputation as a “financial heavy-hitter” took a hit as his financial troubles became public. By the 2010s, stories of Jirongo’s mounting debts and auctioned properties were making headlines. He fought off an auction of a prime piece of land in Nairobi’s Ruai area (once valued in the billions) as banks came calling. He had public spats with trade union boss Francis Atwoli, who sued him over an unpaid Sh110 million loan. Such news shifted public perception: the man once envied for his riches was now seen as financially embattled and perhaps imprudent. In the eyes of many, Jirongo became a cautionary tale – proof that easy money eventually exacts its price. This dented his aura; people wondered if his loud pronouncements were partly a desperate bid to stay politically relevant (and immune from prosecution) in order to protect what remained of his fortune.

Yet even with tarnish on his image, Jirongo retained a base level of respect for his role in Kenya’s political history. He was frequently referred to as a “veteran politician” – a nod to his decades on the scene and the fact that he had once been at the epicenter of power. In talk shows and rallies, he spoke with the gravitas of experience, recounting anecdotes of Moi-era politics and offering advice to younger leaders. This elder statesman posture, however, was undercut by memories of the controversies that clung to him. For every person who applauded Jirongo’s frankness or past contributions (like championing youth in politics), there was another who dismissed him as “part of the problem that led Kenya astray.” The nickname “Jirongo” for the Sh500 note, once a marker of influence, today evokes a chuckle – it reminds people of an era of cash-fueled impunity, and by extension, of Jirongo’s complicity in it.

In sum, public perception of Jirongo has been a study in contrasts. To some, he was the ultimate political operator – savvy, resourceful, and unafraid to play rough. To others, he evolved into a paradoxical figure: the insider-turned-outsider who spoke against the very vices he once indulged. Perhaps the most fitting description came from a social media quip upon news of his passing: “Jirongo was both a symptom and a narrator of Kenya’s corruption – he played the game, then spent years telling us how the game is rigged.” Love him or loathe him, Kenyans could not deny that Cyrus Jirongo was a larger-than-life character who left an indelible imprint on the nation’s political psyche.

Wealth, Woes and the Erosion of Political Capital

By the twilight of his career, Cyrus Jirongo’s fortunes – both political and financial – had taken a dramatic turn. The man who once strode the corridors of power with a limitless checkbook found himself mired in debt and legal battles, his earlier bravado tempered by harsh economic reality. These financial struggles did not just impact his lifestyle; they effectively sapped his political capital and influence.

The cracks began showing in the late 2000s as creditors started pursuing Jirongo for unpaid loans. As detailed earlier, the legacy of his 1990s dealings was a mountain of unresolved debt. Government liquidators and banks steadily caught up to the once “untouchable” tycoon. The reckoning reached a crescendo in 2017, when the High Court officially declared Jirongo bankrupt over a KSh700 million debt he owed to a businessman, Sammy Kogo. The case revealed a complicated web of borrowing: Jirongo had secured a large loan from National Bank using properties as collateral; the bank auctioned those properties when he defaulted, which triggered Jirongo’s obligation to compensate the original owner – an obligation he failed to fulfill. The bankruptcy order meant that, by law, Jirongo was disqualified from holding public office and any assets he still owned could be seized. It was a stunning downfall for a man who once moved billions with a phone call. Though he managed to get the order suspended to continue his presidential run that year, the damage to his credibility was done.

Suddenly, Jirongo was on the defensive, fighting court case after court case. He publicly insisted “I am not bankrupt” and framed the issues as normal business disputes blown out of proportion – even as news of estate auctions and unpaid creditors kept emerging. His Nairobi properties in high-end areas like Karen and Upper Hill were reportedly on the line. In political circles, former allies distanced themselves, and opponents seized on his misfortunes as proof of unfitness. It is hard to project strength on the campaign trail when bailiffs are literally at your door.

This financial turmoil eroded Jirongo’s patronage power. In the 90s he had bankrolled election campaigns (his own and others’) and greased political wheels with ease. By the late 2010s, he could barely fund his outings, let alone sponsor proteges. Politics in Kenya often runs on money, and with Jirongo’s purse strings tight, his relevance waned further. Young politicians from his home region who might have once sought him out for support now looked to other wealthy backers. Jirongo’s decline in wealth translated to a decline in clout – a reality he no doubt understood painfully well.

Moreover, his financial woes became part of his public narrative, adding to a perception of vulnerability. When he spoke out against corruption or government excess, detractors would retort: “Fix your debts first, then lecture others.” It was easy for critics to claim that Jirongo’s attacks on current leaders were less about principle and more about frustration over his own lost fortunes. The aura of power that once surrounded him had dissipated; no longer was he the kingmaker with a bulging briefcase, but rather a cautionary figure – a reminder that political patronage money can evaporate, and today’s power broker can become tomorrow’s pauper.

Jirongo’s story in this phase is also interwoven with Kenya’s growing institutional assertiveness. The fact that courts could declare him bankrupt and that enforcement agencies pursued debts signaled a shift from the era when a call from State House could halt such troubles. In a way, the institutions he once circumvented finally caught up. This had a humbling effect on Jirongo, who in his final interviews struck a more reflective tone. He spoke about the need for financial discipline in public service and lamented how “easy money” had corrupted Kenyan politics, almost as if cautioning a new generation not to follow in his footsteps.

Despite these struggles, Jirongo did not entirely lose his fighting spirit. As late as 2022, he was still campaigning – running for governor and participating in by-election rallies – suggesting a refusal to be written off. But there was poignancy to it: here was a man who once commanded national headlines now focusing on local races and endorsing other candidates, a sign that his role had shifted from principal to surrogate elder. He was received respectfully at events (age and experience still count for something), but the rockstar charisma of the 90s was long gone. What remained was a seasoned politician with scars to show – some from the political battlefield, and many self-inflicted through financial misadventure.

In reflecting on Jirongo’s journey, one sees a Shakespearean arc – a rise enabled by patronage and audacity, and a fall accelerated by hubris and the inexorable currents of justice. His financial downfall did not just curtail his lifestyle; it symbolized the end of an era where impunity reigned. For Kenya, it served as a subtle vindication that no matter how long it takes, the bills eventually come due. And for Cyrus Jirongo, it was the final chapter in paying the price – literally and figuratively – for a career built on the nexus of money and politics.

In the end, Jirongo’s legacy is one of contradiction: he will be remembered as the swaggering YK’92 kingmaker who helped a dictator cling to power, as the businessman who grasped for deals too big to handle, as the politician who kept reinventing himself to stay relevant, and as the candid voice who occasionally pierced through Kenya’s facade of decorum to expose uncomfortable truths. His life is a mirror held up to Kenya’s own post-1990 journey – full of grand promises, sordid deals, spectacular highs and crushing lows. Jirongo’s story, with all its compelling twists, will undoubtedly be studied for what it reveals about the institutions, norms, and changing fortunes of Kenyan politics.