Early Life Among the Giriama People

Mekatilili wa Menza (born Mnyazi wa Menza) was born in the 1860s (some sources say 1840s) in Mutsara wa Tsatsu village, in present-day Kilifi County of coastal Kenya. She was the only daughter in a family of five children, with four brothers. Her name “Mekatilili” reflects Giriama naming customs—it means “mother of Katilili,” after her only son Katilili. Raised among the Giriama, one of the nine Mijikenda ethnic groups of Kenya’s coast, Mekatilili grew up in a community with a rich cultural heritage of independent governance by councils of elders and deep spiritual traditions rooted in sacred forest shrines (kayas). As a young woman she married a man named Dyeka wa Duka and had children, but she was widowed early in life. This status of widowhood, ironically, helped enable her leadership later on – Giriama customs allowed an older, widowed woman more freedom to speak before men and elders than married women typically could. Mekatilili’s formative years were marked by upheavals: one of her brothers was kidnapped by Arab slave traders in the 1880s, a trauma that, according to oral history, she linked to a famous Giriama prophecy of a heroine named Mepoho who foretold the coming of foreign “strangers with hair like sisal” to their land. This prophecy’s echoes would later fuel Mekatilili’s resolve to defend Giriama sovereignty and traditions.

British Colonization at the Coast (Early 20th Century Context)

By the turn of the 20th century, Kenya’s coastal region was under increasing control of the British Empire. After the 1885 Berlin Conference and the establishment of the Imperial British East Africa Company in 1888, British authorities gradually imposed their rule over coastal communities. In 1895, Britain declared the East Africa Protectorate, and by 1920 the territory was a formal colony. Initially, the Giriama – who lived in semi-autonomous villages inland from Malindi – had relatively little direct contact with Europeans. However, this changed sharply in the years just before World War I. British colonial administrators like Arthur Champion and C.W. Hobley sought to integrate the Giriama into the colonial system. They imposed new taxes (such as a hut tax) and restrictive laws, encroached on Giriama trade, and tried to conscript young Giriama men for forced labor on plantations or as porters for the army. The British also attempted to reshape local governance by appointing “headmen” and local councils in 1913 to administer Giriama areas – effectively bypassing or overruling the traditional council of elders who had long governed Giriama society. This was an affront to Giriama political culture, which had no centralized chiefs and valued clan autonomy and elders’ consensus. At the same time, missionaries and colonial schools were introducing new cultural pressures, from European dress to Christianity, which some Giriama felt threatened their way of life. In summary, by the early 1910s the stage was set for conflict: the British were demanding taxes and labor and undermining Giriama traditions, and resentment was rising among the Giriama people.

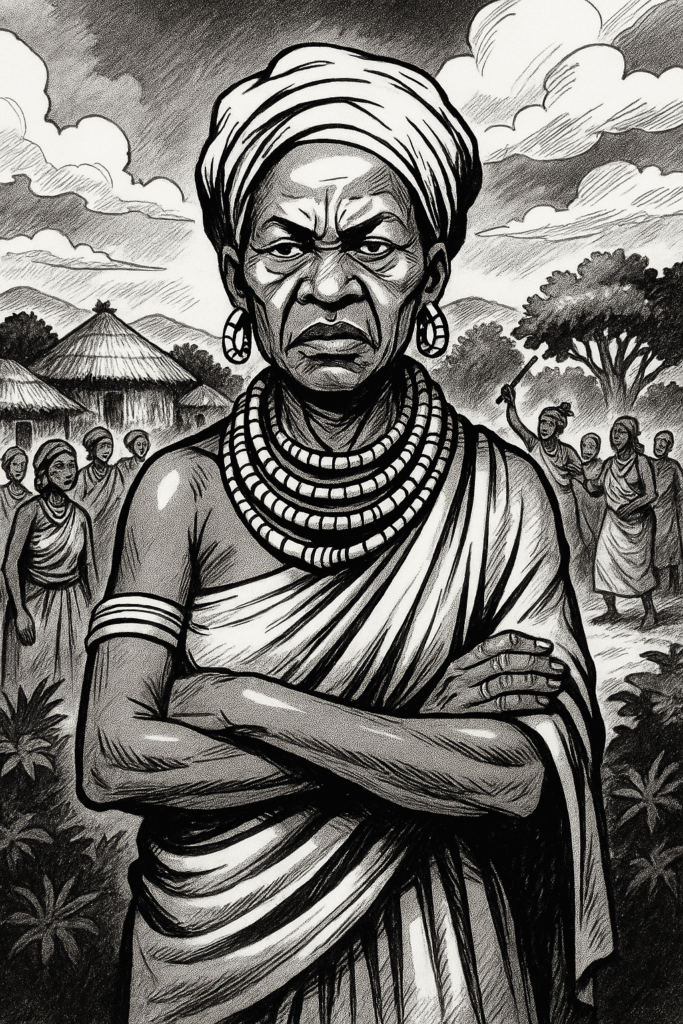

Mekatilili’s Rise and the Organization of Resistance

Against this backdrop, Mekatilili wa Menza emerged as an unlikely but formidable leader of Giriama resistance. She was deeply troubled by the erosion of Giriama autonomy and culture under colonial rule. In a society that was patrilineal and male-dominated, Mekatilili leveraged the few avenues open to women of her status – she was a respected widow and a devout follower of traditional customs – to voice dissent. Charismatic and bold, she began traveling from village to village rallying her people. Mekatilili used the Kifudu, a sacred Giriama funeral dance, as a tool of mobilization: she would perform this dance in marketplace gatherings as a signal to convene meetings and then deliver passionate speeches urging resistance. The Kifudu dance, normally reserved for mourning rites, was repurposed by Mekatilili as a unifying ritual – its performance attracted crowds and built a sense of communal solidarity and urgency.

Mekatilili also found an important ally in a respected elder and traditional medicineman, Wanje wa Mwadorikola. Together, the two became the core organizers of the Giriama resistance. In mid-1913 they called a grand assembly at Kaya Fungo, the principal sacred shrine and meeting ground of the Giriama. Thousands attended this gathering deep in the forest. There, under Mekatilili and Wanje’s direction, Giriama men and women swore powerful oaths of unity and defiance: the men took the fisi oath and the women the mukushekushe oath, swearing never to cooperate with British authorities in any way. These oaths were more than symbolic – in Giriama belief, breaking such an oath could bring death or curse upon oneself. Indeed, Mekatilili’s movement was imbued with spiritual resistance: participants were warned that any “traitors” who betrayed the cause or adopted the foreigners’ ways (such as wearing European clothes or attending mission schools) would have a kiraho (curse) cast upon them. According to colonial reports, this widespread oath-taking struck fear among collaborators; even British officials noted that “every Giriama is much more afraid of the kiraho (oath) than of the government”. By blending traditional religion with anti-colonial politics, Mekatilili built a grassroots movement that was both a cultural revival and a rebellion. She urged the Giriama to refuse hut taxes, boycott colonial labor demands, and reject the authority of British-appointed chiefs, advocating instead for a return to their own customs and economic self-sufficiency.

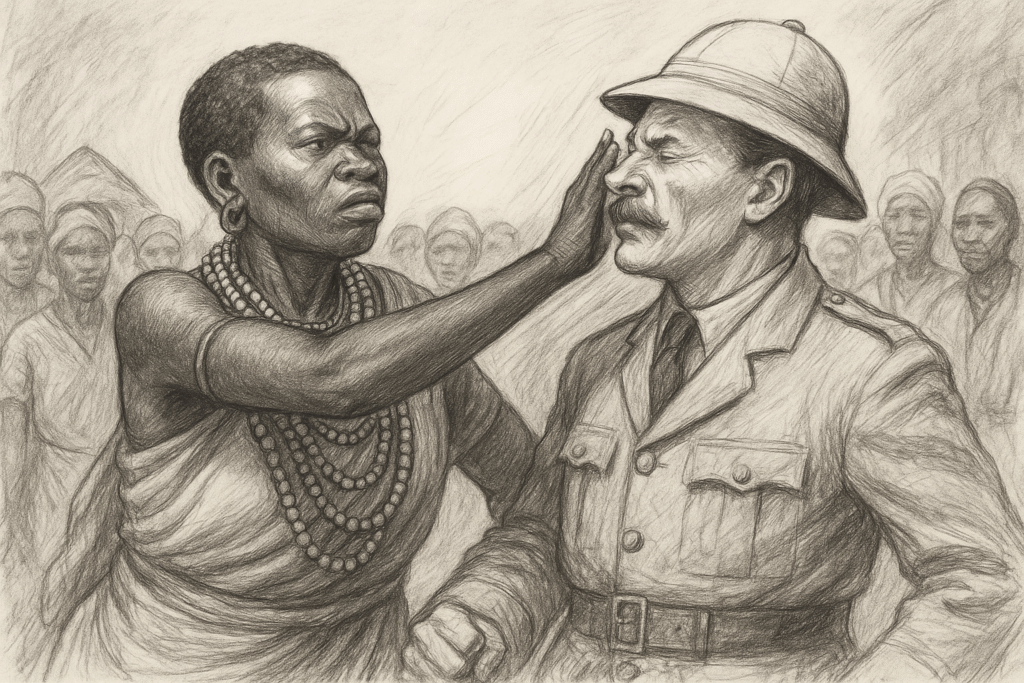

Confrontation with Colonial Authorities (1913)

Mekatilili’s bold activism soon led to direct confrontation with the colonial authorities. The flashpoint came on August 13, 1913, when Assistant District Commissioner Arthur Champion convened a baraza (public meeting) with Giriama leaders at a place called Chakama. Champion’s aim was to quell the brewing dissent and to press the Giriama to provide young men for service (likely as soldiers or porters) in the British forces, as World War I loomed. Mekatilili attended this meeting and dramatically challenged Champion in front of the gathered crowd. In what has become a famous incident, she brought a live hen with her chicks into the meeting. Mekatilili released the mother hen and dared Champion to try and catch one of her chicks. When the British officer reached down to grab a chick, the hen furiously pecked his hand, to everyone’s astonishment and Champion’s humiliation. Mekatilili seized the moment to declare, “This is what you will get if you try to take one of our sons,” likening the protective mother hen to the Giriama who would defend their youth. Some accounts even say that during a heated exchange Mekatilili slapped Arthur Champion across the face, an almost unthinkable act of defiance for an African woman under colonial rule.

The response from the British was immediate and brutal. Stung by the public disrespect and refusal to submit, Champion and his officers opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing several Giriama men and women. This bloodshed inflamed the situation, essentially igniting what would be known as the Giriama Uprising of 1913–1914 (locally called Kondo ya Chembe, meaning “Champion’s War”). In retaliation for Giriama intransigence, colonial forces soon carried out punitive expeditions: they burned Giriama villages, seized livestock and food stores, and even razed Kaya Fungo, the sacred forest stronghold of the Giriama. Mekatilili herself became the primary target for the colonial administration, which saw in her the catalyst of the resistance.

Arrest, Exile, and Daring Escape

On October 17, 1913, Mekatilili wa Menza and Wanje wa Mwadorikola were captured by British officers. They were arrested and quickly sentenced to five years of exile for sedition and resisting colonial rule. The authorities banished the two leaders to the far end of British East Africa – Mekatilili was interned at a remote prison in Kisii, in western Kenya near Lake Victoria, over 700 kilometers from her coastal homeland. The choice of Kisii for detention was likely deliberate: it was about as distant and culturally different from Giriama country as one could get within Kenya, minimizing the risk of her influencing her people.

Yet even in captivity Mekatilili did not submit quietly. Colonial records indicate that while imprisoned, she boldly lectured Arthur Champion (who visited the jail) about the harm British policies were doing. She complained about the “cultural changes” being forced on the Giriama – such as the use of currency (rupees), new fashion like short dresses on Giriama women, and general moral decline – and she demanded an end to the indirect rule system of British-appointed chiefs, insisting the Giriama be allowed to return to their traditional self-governance. Her outspokenness only convinced the British that she was dangerous and unrepentant.

Then, in a remarkable turn of events, Mekatilili and Wanje escaped from exile. According to oral history, after only about six months in detention, in January 1914 the two managed to slip away from Kisii prison. It’s said that on January 14, 1914, they “walked free” – possibly released due to a ruse or simply escaping when an opportunity arose – and then trekked on foot for hundreds of miles across Kenya back to the coast. Stories abound of how they survived this epic journey: traveling by night, hiding in forests, and navigating a country in turmoil (World War I had just broken out and colonial troops were mobilizing). The distance from Kisii to Malindi is over 700 km of difficult terrain; that Mekatilili, a woman in her 50s or 60s, undertook it is testament to her determination. When Mekatilili reappeared in her home district after the arduous trek, the colonial authorities were astonished – and alarmed. She picked up right where she left off, encouraging the Giriama to continue resisting British demands.

The British, meanwhile, were still in active campaign against the Giriama resistance. Open hostilities had continued into 1914. Colonial troops had partially destroyed Kaya Fungo with dynamite and engaged in skirmishes with Giriama fighters. The Giriama Uprising coincided with the early months of World War I, and the British, now fighting a war with Germany (including in neighboring German East Africa), could ill afford a protracted rebellion on the Kenyan coast. In August 1914, just days after Mekatilili’s return, she was rearrested by the British – this time under even tighter security. The colonial regime sent her far away to prison in Kismayu, Somalia, which was then part of the British domain, hoping to remove her permanently from her base of influence. Wanje wa Mwadorikola was also recaptured and punished. Despite these efforts, pockets of Giriama resistance persisted.

Later Years and Continued Defiance

Mekatilili’s second exile coincided with the winding down of the Giriama Uprising. By late 1914, facing superior firepower and harsh reprisals, the Giriama resistance was largely suppressed. The British imposed heavy fines on the Giriama (demanding vast amounts of rupees or livestock), forced them to surrender arms, and even compelled some communities to relocate from their lands north of the Sabaki River as punishment. Under duress, the Giriama paid part of the fines, provided some laborers, and endured the occupation of their territory by colonial troopsh. However, the resistance was not in vain – the upheaval clearly made an impact. Within a few years, some punitive measures were reversed: by 1917, the colonial government allowed the Giriama to move back to their north bank lands, an official admitting that “if injustice has been done it is our duty to repair it”. In 1919, after World War I had ended, the British even returned the sacred Kaya Fungo to the Giriama community. These concessions indicated that the colonial authorities recognized they had overstepped, and that Mekatilili’s campaign had forced them to soften their grip on the Giriama to avoid further unrest.

Meanwhile, Mekatilili wa Menza gained her freedom as World War I drew to a close. In 1919, she was released from detention in Somalia and allowed to return home permanently. After five long years in exile, Mekatilili came back as something of a popular hero among her people. Despite all she had endured, she reportedly remained defiant in spirit. Back in Giriama territory, she resumed a role of leadership in community affairs – though now in a more symbolic and advisory capacity due to her age. She was given a position in the women’s council at the restored Kaya Fungo, while her comrade Wanje wa Mwadorikola joined the men’s council of elders. Mekatilili continued to advocate for the preservation of Giriama traditions and self-determination, even as the British colonial system consolidated its rule in the 1920s. Having been one of the very few women to ever lead an armed resistance in Kenya’s history, she lived to see her people regain a measure of autonomy in local matters, though full freedom was still decades away.

Mekatilili wa Menza died of natural causes a few years later, in 1924 (some sources say 1925). She was around 70–80 years old. According to oral lore, she collapsed while pounding grain in a field – a humble end to the life of a remarkable woman who had shaken an empire. Mekatilili was laid to rest in Bungale, in the Dakatcha woodland of Magarini (near Malindi), not far from the land she fought to defend. Her passing received little attention from colonial authorities at the time, but her people remembered. The flame of resistance she lit would later inspire other Kenyan freedom fighters in the decades to come.

Significance as Kenya’s Early Female Freedom Fighter

Mekatilili wa Menza holds a singular place in Kenyan history as one of the earliest and most prominent female freedom fighters against colonial rule. At a time (1910s) when African women were expected to have no political voice, and colonialism’s patriarchy intersected with traditional gender constraints, Mekatilili broke the mold. She demonstrated extraordinary courage by openly defying British officials, rallying warriors, and enduring imprisonment – actions virtually unheard of for women in that era. Her leadership in the Giriama uprising predates better-known Kenyan struggles (like the 1920s Kikuyu protests or the Mau Mau rebellion of the 1950s) by many years. In fact, Mekatilili’s revolt in 1913–1914 can be seen as a forerunner to later anti-colonial movements: it combined grievances over land, labor and taxation with a strong defense of cultural identity – themes that would resurface throughout Kenya’s freedom struggle. She proved that women, too, could be catalysts for resistance and “fight for the people” even in a deeply patriarchal context. This legacy has made Mekatilili a symbol of women’s agency in Kenya’s history. Historian Cynthia Brantley noted that Mekatilili’s campaign nearly shut down the colonial system in Giriama country as people rallied behind her calls to reject colonial demands. Decades later, scholars and writers would celebrate Mekatilili for having “opened the way for feminist struggle” in Kenya.

However, for a long time Mekatilili’s story was marginalized in mainstream narratives of Kenya’s independence. Post-independence histories tended to lionize male leaders (such as Koitalel Arap Samoei of the Nandi or later Jomo Kenyatta and Dedan Kimathi) while grassroots figures like Mekatilili remained lesser known. It was not until the 1980s that Mekatilili wa Menza’s name resurfaced prominently, as Kenyan activists and writers looked back for inspirational figures outside the male-dominated pantheon. During Kenya’s feminist movement in the 1980s, Mekatilili was reclaimed as an icon of women’s resistance, a home-grown role model of a woman who stood up to injustice. Books and stories about heroic Kenyan women began including Mekatilili as a pioneer – for example, Rebeka Njau’s Kenya Women Heroes highlighted Mekatilili’s exploits. Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and others have praised her as a moral beacon of anti-colonial defiance. Thanks to such efforts, Mekatilili is now recognized not just as a Giriama hero, but as a national heroine of Kenya.

Cultural and National Legacy

Today, the legacy of Mekatilili wa Menza is honored both in her coastal homeland and across Kenya. Among the Giriama and the broader Mijikenda community, her memory is kept alive through oral history and annual celebrations. In Kilifi County (Malindi area), locals hold the Mekatilili wa Menza Cultural Festival every year around August, commemorating her historic resistance. Crowds gather to reenact the Kifudu dance, recount Mekatilili’s deeds, and celebrate Giriama culture that she fought to protect. This festival is a time of pride for the community and has even drawn government officials to acknowledge her contribution.

Nationally, Mekatilili’s stature has grown significantly since Kenya’s return to multi-party democracy and the reform era of the 2000s. In 2010, almost a century after her uprising, the Kenyan government officially recognized Mekatilili wa Menza as a hero of the independence struggle. During the 2010 Mashujaa Day (Heroes’ Day) celebrations – a holiday that honors Kenya’s freedom fighters – a monument in Mekatilili’s honor was unveiled in Malindi. A bronze statue of Mekatilili now stands proudly in the center of Mekatilili Garden (formerly Uhuru Garden) in Malindi town. The statue depicts her mid-stride with an arm outstretched, symbolizing her fearless leadership. The garden around it was renamed after her and serves as a public reminder of her “fierce resistance and unyielding courage”. Each Mashujaa Day (October 20th), the monument becomes a focal point for remembrance ceremonies on the coast, and local leaders lay wreaths in her memory. In 2012, a second statue of Mekatilili was reportedly unveiled and dedicated at a public park (also called Uhuru Gardens) in Nairobi, signifying that her heroism is recognized at the national level as well.

Mekatilili’s legacy has also entered popular culture and education. Her dramatic story has been the subject of biographies, school textbooks, academic research, and even art projects. For instance, a 2020 digital comic book “Mekatilili wa Menza: Freedom Fighter and Revolutionary” was created by Kenyan artists to introduce her story to younger audiences. On August 9, 2020, the tech giant Google celebrated Mekatilili with a dedicated Google Doodle on its homepage. The doodle, which was seen by millions around the world, portrayed Mekatilili leading her people, and it marked the 100+ years anniversary of her campaign by honoring her as the first Kenyan woman to fight against colonial injustices. Such recognition on a global platform underscored the growing appreciation of Mekatilili’s significance beyond Kenya’s borders.

In Kenya, Mekatilili wa Menza is now firmly established among the pantheon of freedom fighters. She is often mentioned alongside later heroes like Harry Thuku, Mekason Ndeda, or Mau Mau women like Field Marshal Muthoni, highlighting that the spirit of resistance in Kenya had powerful female champions from the very start. Her story is a poignant reminder that the struggle for freedom was waged not only by famous men with titles, but also by rural women armed with nothing but their conviction, cultural unity, and the will to be free. Mekatilili’s courageous stand against forced labor, taxation, and cultural erasure left an indelible mark on Kenyan history. As one Kenyan singer and activist put it, “Those days women were not at the front in fighting for justice. [Mekatilili] was brave enough to stand up and fight for the people”. Today, schoolchildren learn about “the legendary Mekatilili” as a national folk hero, and her narrative inspires ongoing discussions about women’s roles in leadership and resistance.

Mekatilili wa Menza’s life exemplifies the intersection of cultural preservation and political resistance. She fought not only against colonial exploitation, but also for the right of her people to live by their own customs and beliefs. In doing so, she became a guardian of a way of life that colonialism sought to extinguish. Her legacy endures in the continued pride of the Giriama people and in Kenya’s recognition of its forgotten heroines. In the broader scope of African history, Mekatilili’s revolt is one of the early 20th-century uprisings that demonstrated that colonial rule, even at its height, was not unchallenged – and that leadership and heroism could emerge from the most unexpected quarters, including a courageous widow from a small Kenyan village who rallied her people with a dance and an oath.

References (APA style):

- Brantley, C. (1981). The Giriama and Colonial Resistance in Kenya, 1800–1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. capiremov.orghistorymatters.sites.sheffield.ac.uk

- Carrier, N., & Nyamweru, C. (2016). Reinventing Africa’s National Heroes: The Case of Mekatilili, a Kenyan Popular Heroine. African Affairs, 115(461), 599–620. en.wikipedia.orgora.ox.ac.uk

- Loughran, L. (2021). Mekatilili Wa Menza and the Giriama War. History Matters (University of Sheffield). historymatters.sites.sheffield.ac.ukhistorymatters.sites.sheffield.ac.uk

- Capire. (2021, July 22). Mekatilili wa Menza: Anti-Colonial Struggle in Kenya. [Online Magazine]. capiremov.orgcapiremov.org

- Gitaa, M. (2020). #BHM Mekatilili wa Menza: Kenyan Prophet and Warrior (Part 2). Meeting of Minds UK. meetingofmindsuk.ukmeetingofmindsuk.uk

- Jaroya, M. (2021). Mekatilili wa Menza. Lughayangu – African Languages and Cultures. lughayangu.comlughayangu.com

- Nircle. (2025). Monument of Defiance: Honoring Mekatilili wa Menza. Feed.Nircle.com. feed.nircle.comfeed.nircle.com

- Wikipedia. (2025). Mekatilili Wa Menza. Retrieved Oct 24, 2025.