Nicholas Kiprono Kipyator arap Biwott was born in 1940 in Chebior Village, Keiyo District (in present-day Elgeyo-Marakwet), into a humble Kalenjin family. His parents, Cheserem and Maria Soti, were progressive for their time – his father was an enterprising farmer-turned-businessman, and his mother stressed education for all her children. Biwott attended local schools – first Mokwo Primary and then Tambach Intermediate (1951–54) – before earning admission to the prestigious Kapsabet High School, where he studied from 1955 to 1958. Academically bright and a natural leader, the diminutive Biwott (only 5’5” tall) nevertheless commanded respect among peers, even being given the best bed in his dormitory as a mark of esteem.

In 1961, Biwott achieved a historic milestone: he became the first Kenyan to study in Australia. He enrolled at Taylors College in Melbourne, then proceeded to the University of Melbourne (1962–1964) on scholarship. There, he earned a Bachelor of Commerce degree and a Diploma in Public Administration, majoring in economics and political science. Ever eager to learn, Biwott briefly returned to Kenya but sought further studies. In 1966 he attended the Kenya Institute of Administration for a public administration course, and even returned to Melbourne for a Master’s program in economics. Though he did not complete the master’s (government permission for extended study was denied), the foundation was set for a career straddling public service and economics. This strong educational background – rare among Kenyan civil servants of his generation – later bolstered Biwott’s technocratic image and helped him forge international connections, including early ties with Australia and Israel that would prove influential in his business and political dealings

From District Officer to Moi’s Inner Circle: Rise to Power

Biwott’s return to Kenya in 1964 marked the start of a meteoric rise through the ranks of government. He began as a District Officer in Meru (South Imenti and Tharaka areas) during Jomo Kenyatta’s presidency, where he gained administrative experience and even helped implement the “Million Acre” resettlement scheme for landless Kenyans (including Mau Mau veterans). His diligence did not go unnoticed. By 1968, Biwott was appointed Personal Assistant to the Minister of Agriculture – a post that brought him under the wing of Bruce McKenzie, a powerful minister with international ties. In this role, the young Biwott helped shape agricultural policy, coordinate cereal production and fertilizer programs, and even engage in regional projects like the jointly-run East African Railways and Airways. These early experiences gave Biwott a taste of high-level governance and introduced him to the art of inter-ministerial coordination.

A pivotal turn in Biwott’s trajectory came in the early 1970s. In 1971 he was promoted to Senior Secretary at the Treasury under Minister of Finance Mwai Kibaki (Kenya’s future third President). There, Biwott established Kenya’s External Aid Division, cultivating cultural and financial links with Western nations. President Kenyatta himself took note: in 1972, on Kenyatta’s recommendation, Biwott was transferred to the Ministry of Home Affairs. At Home Affairs, he worked directly under Vice-President Daniel arap Moi (who was then minister in charge). Biwott served as an Under Secretary from 1974, focusing on African regional cooperation and “good neighborliness” policies toward bordering countries. This period forged a close bond between Biwott and Daniel arap Moi, the man he would loyally serve for decades. Indeed, when Kenyatta died in 1978 and Moi assumed the presidency, Biwott was one of the Kalenjin technocrats ready to help Moi consolidate power. Moi immediately promoted Biwott to Deputy Permanent Secretary in the Office of the President in 1978 – placing him at the nerve center of state power as Moi navigated a delicate transition from Kenyatta’s rule.

In 1979, in Kenya’s first general election under President Moi, Biwott entered elective politics. Backed by Moi’s ruling party KANU, Biwott won (unopposed) the parliamentary seat for Keiyo South, a tenure he would hold for 28 uninterrupted years (1979–2007). Simultaneously, Moi elevated him straight into the Cabinet as a Minister of State in the President’s Office. This initial ministerial docket was wide-ranging: Biwott oversaw Science and Technology, Cabinet Affairs, Immigration, and Land Settlement all at once. Such broad responsibilities at a go were unusual for a first-time minister, signaling the extraordinary trust Moi placed in Biwott from the outset. Biwott quickly made his mark – for instance, in 1979 he spearheaded the establishment of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) as a state corporation to advance medical science.

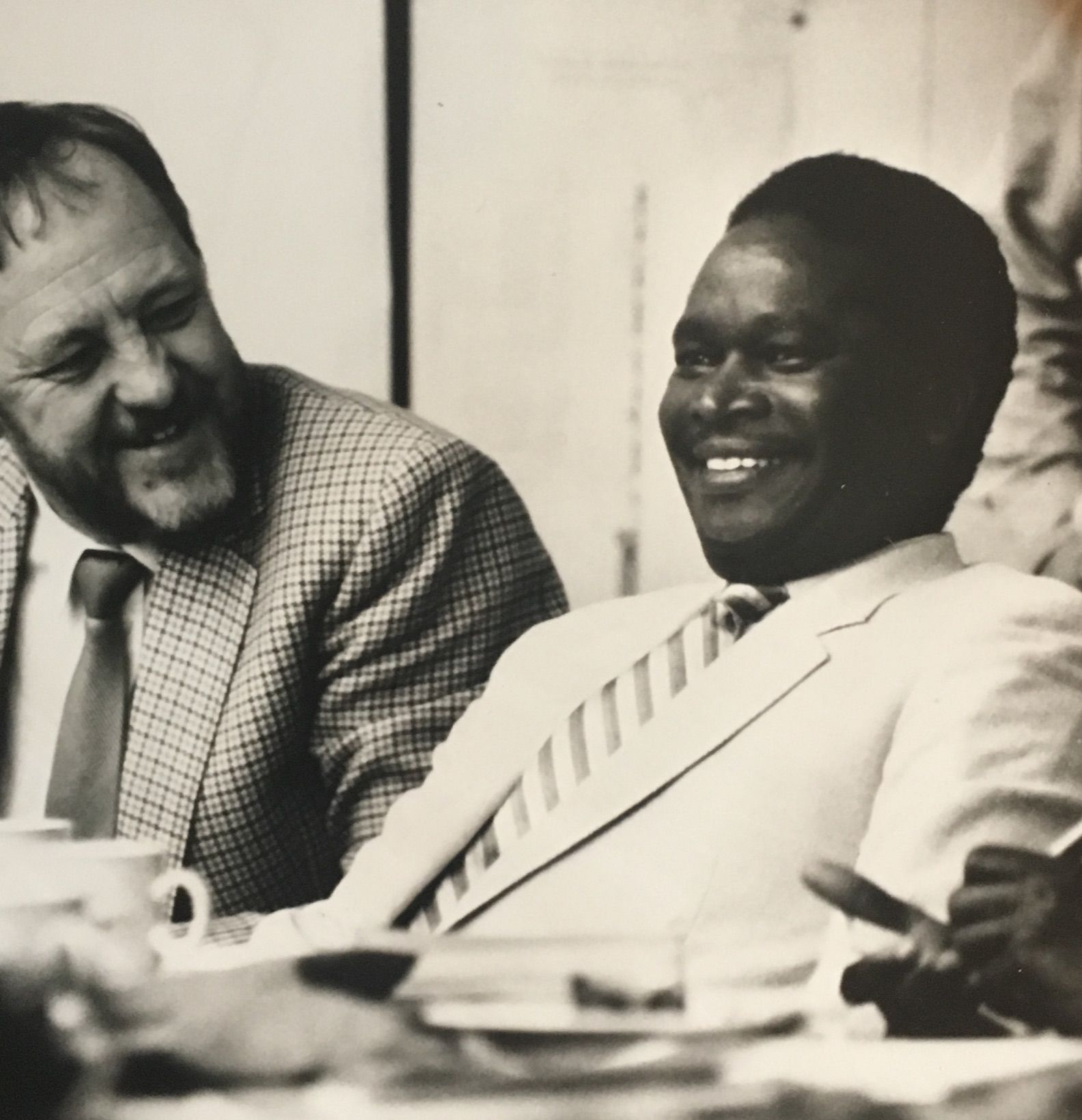

Throughout the 1980s, Biwott’s star only rose higher as he became arguably President Moi’s most trusted lieutenant. He was often described as Moi’s “right-hand man”, operating mostly behind the scenes yet wielding immense influence. In 1982, Moi appointed him Minister for Regional Development, Science and Technology. The following year, after the tumultuous attempted coup of August 1982, Moi reshuffled the cabinet and handed Biwott one of the most critical portfolios – Energy. As Minister of Energy (1983–1991), Biwott oversaw ambitious projects to expand Kenya’s energy infrastructure: he founded the National Oil Corporation, launched rural electrification programs, and pushed for dam construction to boost power generation. Notably, he presided over the commissioning of the Turkwel Gorge hydroelectric dam in 1986 – a massive project touted to energize the nation, albeit one later mired in allegations of corruption and cost inflation (more on this later). By the late 1980s, Biwott had become a fixture of Moi’s inner circle, present at the highest levels of decision-making. “Nicholas Kipyator arap Biwott was at the epicentre of power during the 24 years that President Daniel arap Moi was in office,” observed The Standard, noting that he was widely regarded as the “Man Behind the Throne” in Moi’s government.

Ministerial Power and the “Total Man” Persona

As a cabinet minister, Biwott held an extraordinary array of portfolios over his career, earning a reputation as an all-purpose Mr. Fix-It in the Moi regime. Between 1979 and 2002 he served in at least eight different ministerial posts, ranging from energy and regional development to trade and East African cooperation. This included a second stint as Minister of East African Cooperation and Trade (1998–2002) during which he helped rekindle regional integration efforts – chairing the East African Community’s Council of Ministers and facilitating a COMESA free trade area. By the end of Moi’s era, Biwott had become one of Kenya’s most experienced statecraft operators, having sat in the cabinet for nearly the entire length of Moi’s 24-year rule (save for a brief exile from 1991 to 1997, which we will address). His longevity in government and ability to thrive in diverse roles earned him both admiration and fear. Colleagues marveled at his work ethic and grasp of detail; at the same time, many whispered that crossing Biwott’s path was political suicide. Indeed, he acquired nicknames that reflected his clout – “Total Man,” “Mr. Fix-It,” “Karnet (the Steel),” even “King in Waiting” – underscoring the aura that he was not a man to be crossed. As one account put it, “Anyone who [crossed Biwott] in the Moi government was sacked”.

It was during a parliamentary debate in the late 1980s that Biwott famously gave himself the moniker “Total Man.” Responding to critics in the House who questioned his integrity, Biwott asserted that for a leader, being a man was not enough – one had to be “a man, a total man.” This strange tautological boast became legend. The press and public seized on the phrase, cementing “Total Man” as Biwott’s enduring label. In Kenyan political lore, Total Man came to symbolize Biwott’s image as an all-powerful, omnipresent force – a man involved in everything, with seemingly total influence. The nickname was at once a tribute to his power and a subtle jibe at the hubris it implied. Biwott’s own style reinforced this mystique: he was notably reclusive and tight-lipped in public, rarely granting interviews or making unscripted remarks. His speeches were brief and cautious. He preferred to work the levers of power quietly, in the shadows. Biwott even avoided eating or drinking at public functions and kept his travel itineraries secret – habits born of extreme security consciousness, if not outright paranoia, that he shared with a few other Moi-era barons. The man cultivated an air of mystery.

One illustrative episode of Biwott’s behind-the-scenes sway was how he returned to the Cabinet in the late 1990s. After being dropped in 1991 (amid scandal, as discussed later), Biwott made a comeback just in time for the 1997 elections. Moi appointed him Minister of State in 1997, and then Minister of Trade and Industry in 1999, despite lingering public reservations. The move signaled Moi’s enduring reliance on his “Total Man” for tough tasks. In these final years of KANU rule, Biwott busied himself courting foreign investors and instituting reforms (he introduced Kenya’s first intellectual property law and even set up a Tourist Police unit to protect the vital tourism sector). Insiders noted that even after Kenya’s return to multiparty politics, Biwott was the fixer Moi turned to when in trouble – whether it was mending fences with restive political factions or managing sensitive state projects. Little happened in KANU or government without Biwott’s input. “Mr Biwott was seen to be Mr Moi’s fixer who fought epic wars with fellow politicians, civil society groups and the media,” writes the Business Daily. He acquired a reputation as Moi’s enforcer, willing to take on opponents to protect the regime. Cabinet colleagues sometimes resented his influence, but few dared challenge him openly. With Moi’s backing, Biwott reportedly had a hand in deciding senior appointments and dismissals. It was joked in political circles that a mere whisper from Biwott into President Moi’s ear could make or break careers. This climate of fear was not unfounded – The Standard recalls that Biwott was “widely acknowledged as the man not to cross in the Moi government”. Such was the clout of the Total Man at his peak.

An Empire of Business: Yaya Centre, Air Kenya, Kenol and More

Parallel to his public service, Nicholas Biwott built an extensive business empire, leveraging the permissive environment that allowed Kenyan civil servants of his era to engage in private enterprise. In the 1970s, the Ndegwa Commission’s recommendations had explicitly permitted public officers to own businesses, aiming to prevent brain drain and indigenize the economy. Biwott enthusiastically took up this opportunity. Starting in the late 1960s, he methodically invested in ventures across agriculture, real estate, transportation, and energy – often acquiring struggling firms and turning them around.

One of Biwott’s earliest ventures was in 1969 when, still a young administrator, he purchased the Eldoret franchise of International Harvester (a farm equipment dealer) and a dairy farm in Kipsenende. He soon expanded into large-scale farming, buying wheat farms (such as the renowned Karo Farm in Uasin Gishu) in the mid-1970s. By 1977, Biwott had entered the aviation sector: that year he acquired a small Nairobi-based safari airline, one which he later developed into Air Kenya. Air Kenya grew into a leading regional airline for tourism and charter flights, a testament to Biwott’s strategy of investing in sectors synergistic with Kenya’s economy (and perhaps useful to the government as well). Biwott was also an avid property investor. In Nairobi’s upscale Hurlingham area, he established the landmark Yaya Centre, a multi-story shopping complex that opened in the 1980s and remains one of the city’s most iconic malls. By the time of his death, the Yaya Centre was among the crown jewels of Biwott’s holdings – a concrete symbol of his wealth and lasting footprint on Nairobi’s skyline.

Biwott’s most significant corporate play was in the oil industry. In 1981, while serving as Energy Minister, he took a personal stake in Kenya Oil Company (Kenol), then a struggling petroleum distributor. Over the next two decades, Biwott (often behind the scenes) helped transform Kenol into a powerhouse. Kenol later merged with Kobil, and by the 2000s Kenol-Kobil was one of East Africa’s largest oil marketing firms, operating hundreds of petrol stations and a major player in fuel imports. The company’s success not only made Biwott enormously rich on paper, but also intertwined his business interests with Kenya’s energy policies. (Critics would argue that Biwott’s dual role as Energy Minister and oil investor was a textbook conflict of interest, though it was legal under Kenya’s rules at the time.) In addition to Kenol-Kobil, Biwott was known to hold stakes in other ventures – multiple ranches and farms, an array of real estate properties, and ventures abroad in Australia and Israel. By the 1990s, he and a handful of other Moi-era barons effectively formed a state-connected business elite, sometimes called “KANUpreneurs.”

Despite the breadth of his portfolio, Biwott kept his business dealings shrouded in secrecy. Many of his investments were held through proxies or numbered companies, making it difficult for the public to trace his true net worth. It was only in 2013, when a Nigeria-based magazine Ventures listed African billionaires, that Biwott’s wealth was put in the spotlight. Ventures estimated Biwott’s fortune at about $1.0–1.65 billion (over KSh 80–140 billion), ranking him among Kenya’s richest individuals alongside the likes of the Kenyatta family. Known assets like Yaya Centre, Air Kenya, and Kenol/Kobil were just the tip of the iceberg; the magazine suggested he had sizable holdings overseas as well. Biwott characteristically neither confirmed nor denied these figures. He had always preferred to operate as the silent tycoon. A diaspora publication noted that Biwott’s “business dealings were in total secrecy, making it hard to determine his net worth”. For decades, this secrecy fueled speculation that much of his wealth may have stemmed from government patronage or even graft. Indeed, some of Biwott’s projects became magnets for corruption allegations (for example, Turkwel Dam, which he signed off on, was later revealed to have been contracted at roughly three times the normal cost amid hefty kickbacks). Nonetheless, there is no doubt that Biwott saw himself as a nationalist entrepreneur. He frequently argued that his companies created thousands of Kenyan jobs and kept profits within Kenya’s economy. By the end of his life, the man who had started as a civil servant with a modest salary had become a business magnate spanning industries – a trajectory entwined with the story of Kenya’s political economy in the Moi era.

The Shadow Government: Influence over Security and Intelligence

Biwott’s power was not confined to his official ministries or businesses – many believed that he also exerted tremendous influence over Kenya’s security apparatus and intelligence network, operating as an unofficial spymaster for President Moi. Though he never held the title of Internal Security Minister or Intelligence Chief, Biwott’s proximity to the President and membership in the inner circle gave him leverage over the coercive instruments of the state. During the 1980s, Kenya was effectively a one-party state (KANU) and dissent was often crushed ruthlessly. Biwott, as a trusted confidant, became deeply involved in maintaining the regime’s grip on power. For instance, after the failed 1982 coup attempt by Air Force officers, Biwott was one of the men Moi relied on to purge disloyal elements and reinforce control. “During the 1982 coup, Mr Biwott helped Moi to deal with the mushrooming opposition in the country,” notes a Kenyan outlet, referring to the crackdown on perceived dissidents that followed. Although details of his involvement are murky, Biwott was reportedly active in coordinating responses through the provincial administration and ruling party machinery to ensure no repeat of such threats.

Within the intelligence community, Biwott was rumored to run what some called a “parallel security system.” Kenya’s official intelligence service (then known as the Special Branch, later the Directorate of Security Intelligence) had its formal leadership, but observers speculated that Biwott had his own loyalists embedded in it. In fact, a leaked account later alleged that “with the advent of multipartyism, Biwott ran a feared parallel security and administrative intelligence [network] whose vicious face was the late Hezekiah Oyugi”. (Hezekiah Oyugi was a powerful Internal Security Permanent Secretary under Moi, and a close associate of Biwott.) This suggests that Biwott and Oyugi might have orchestrated covert operations to surveil and neutralize government critics, independently of other security organs. While such claims are difficult to verify, they were widely believed. Biwott was certainly feared by the security chiefs themselves – it was said that even the Special Branch would brief Biwott before they reported to President Moi. Whether or not that is literally true, it speaks to the perception that Biwott sat at the nexus of information and power.

His influence also extended to censorship and information control. Under Biwott’s watch (either in Energy or as Minister of State), Kenya saw instances of extreme suppression to cover up scandals. A notorious example is the Turkwel Dam affair in the late 1980s. When foreign donors and media raised questions about inflated costs and kickbacks in the dam’s construction – a project Biwott oversaw – the state responded heavy-handedly. According to reports, an expatriate who wrote a letter querying the deal was swiftly expelled from the country, copies of the Financial Times carrying a critical story were seized and destroyed at Nairobi airport, and a Washington Post journalist investigating on-site in Turkana was given 30 minutes to leave the area by authorities. These actions, while carried out in the name of state security, aligned neatly with protecting Biwott’s interests and reputation. It is telling that such a degree of control could be exerted; it implies that individuals at the apex of power – Biwott foremost among them – could marshal the security organs to their personal ends.

Biwott’s own behavior betrayed his deep entanglement with security matters. As mentioned, he lived in perpetual caution: traveling under the radar, employing heavy personal security, and even allegedly using multiple safe houses. Alongside Vice President (and former Interior Minister) George Saitoti, Biwott was considered one of the most “secretive and paranoid” figures of that era. He took elaborate precautions against potential threats – for example, never eating food at public events for fear of poisoning. Such measures suggest he knew very well the deadly games that could be afoot in Kenyan politics (after all, he himself had been accused of ordering assassinations, as we will discuss). Biwott also mastered the art of silence: he rarely, if ever, commented on security operations or allegations in public. Even as human rights groups decried abuses like torture at Nyayo House (the infamous secret police chambers of the 1980s), Biwott kept an inscrutable silence, revealing nothing of the government’s inner workings. This code of omertà only fueled the myth that he was the shadowy puppeteer pulling strings in the background.

It is important to note, however, that much of Biwott’s reputed control over security was speculative – an amalgam of circumstantial evidence, fear-fueled rumor, and the occasional leaked tidbit. Formally, President Moi had other lieutenants in charge of security: from the Special Branch director (the long-serving James Kanyotu, and later others like William Kivuvani and Brigadier Boinett) to powerful ministers like Justus ole Tipis and later Julius Sunkuli. But in Kenya’s personalized power structure, formal titles often mattered less than personal trust. And Moi’s trust in Biwott was nearly absolute. Thus, while documentation is scant, historians generally agree that Biwott was a key player in Moi’s security state – whether coordinating intelligence, overseeing sensitive operations, or deciding the fates of detainees – albeit always in Moi’s name. This dual image of Biwott as both a public minister and a “security baron” in the shadows is central to why he evokes such strong memories in Kenya.

Scandals and Controversies: Murder, Money and Myth

Despite (or because of) his enormous influence, Nicholas Biwott was dogged for decades by scandals and dark allegations. He was often described as “one of the most maligned politicians” in Kenya’s history. Opponents and critics linked him to some of the worst episodes of the Moi era, from grand corruption to political violence. Yet, strikingly, nothing was ever proven against him in a court of law. Biwott’s name surfaced repeatedly in inquiries and the media, but he maintained an iron-clad stance of denial and even aggressively fought back through libel suits. Here, we examine the most notorious controversies: the Robert Ouko murder, the Goldenberg corruption scandal, the cultivation of his “Total Man” mythology (including the bizarre “Bull of Auckland” incident), and Biwott’s lifelong evasiveness in the face of public scrutiny.

The Ouko Murder – “Total Man” under Suspicion

The February 1990 murder of Kenya’s Foreign Minister, Dr. Robert Ouko, stands out as the single most explosive controversy around Biwott. Dr. Ouko was a reform-minded minister in Moi’s cabinet who mysteriously disappeared on February 12, 1990. A few days later, his charred body was discovered at Got Alila hill near his Koru home under gruesome circumstances. The assassination of Ouko – a high-profile Luo politician – provoked national outrage and international pressure for justice. Suspicion quickly fell on figures within Ouko’s own government, given reports that Ouko had fallen out with certain powerful colleagues over corruption revelations during a trip to Washington, DC. In the ensuing investigations, Nicholas Biwott’s name emerged as a prime suspect. President Moi, seeking credibility, invited Britain’s Scotland Yard to send a detective, Superintendent John Troon, to probe the case. Troon’s preliminary report indeed pointed fingers at Biwott (then Minister of Energy) and others in Moi’s inner circle, recommending further investigation of Biwott’s possible role.

Under intense domestic and donor pressure, Moi’s government took the unprecedented step of briefly detaining Biwott and another top official, Hezekiah Oyugi, in connection with Ouko’s murder in late 1990. However, no charges were brought; they were released, and the case stalled amid what many saw as a cover-up. Over the next few years, multiple inquiries into Ouko’s death were launched only to be abruptly shut down before conclusion. A pattern of witness intimidation, mysterious deaths of individuals linked to the case, and official stonewalling plagued the investigations. The Moi government even initially floated a false narrative that Ouko had committed suicide, an explanation met with public riots until it was withdrawn. To Kenyans, Ouko’s murder became the symbol of impunity and “dirty secrets” of the Moi regime – and in that symbolism, Biwott was cast as the arch-villain.

Throughout, Biwott vehemently denied any involvement. He never waivered from insisting on his innocence, calling the allegations against him “a total absurdity.” With characteristic combativeness, he turned to the courts to defend his name. In the 1990s, Biwott filed a barrage of defamation suits against anyone who dared tie him to Ouko’s killing. Authors, newspapers, even a former American ambassador were targets. Notably, when ex-U.S. Ambassador Smith Hempstone published his memoir “The Rogue Ambassador” implicating Biwott in Ouko’s death, Biwott obtained a court order banning Kenyan media from serializing the book. He sued and won large damages – in total over KSh 67.5 million (then an astonishing sum) in libel awards during the 1990s. This aggressive legal warfare had a chilling effect: local media became extremely cautious about naming Biwott in connection with Ouko’s case, even as the public widely presumed his guilt. Biwott’s most famous legal victory came in 1991 when he sued British forensic expert Dr. Ian West and a Kenyan publisher over a report suggesting Biwott’s involvement; the court awarded Biwott hefty compensation, reinforcing his public claim to exoneration.

The matter refused to die, however. After Moi left power, a Parliamentary Select Committee re-investigated Ouko’s murder in 2004–2005 (chaired by MP Gor Sunguh). In its final report of May 2005, the committee boldly recommended that Nicholas Biwott be investigated and prosecuted for Ouko’s murder, citing adverse evidence and motives including power rivalry. The committee even named others – Hezekiah Oyugi (by then deceased), former VP George Saitoti, and ex-State House operative Ibrahim Kiptanui – as having questions to answer. According to the report, Kenya’s leadership at the time believed Ouko was positioning himself (with foreign backing) to challenge for the presidency, which “would be sufficiently supported as a motive” for eliminating him. Biwott, by then an opposition MP, fought back fiercely against these findings. He initially refused to appear before the committee, relenting only under threat of legal summons – and when he did testify in early 2005, it was an acrimonious session by all accounts. Biwott lambasted the inquiry as biased. Ultimately, the government rejected the committee’s report, and no charges were brought (Kenya’s attorney-general cited insufficient evidence, echoing previous inquiries).

To this day, Dr. Ouko’s assassination remains unsolved, and Biwott maintained his innocence to the end. However, the weight of suspicion profoundly shaped his legacy. For many Kenyans, Biwott will forever be entwined with Ouko’s murder – a dark cloud that neither court acquittals nor libel victories could dispel. International observers also took note: documents show that even years later, the U.S. and U.K. quietly barred Biwott from entry due to corruption and Ouko-murder allegations. In 2004, the U.S. State Department revoked Biwott’s visa for alleged graft, and in 2009 the UK High Commission likewise cancelled his travel visa citing those “heavily involved in corruption” and human rights crimes. A Voice of America report on the UK ban explicitly mentioned that “a Scotland Yard investigation into the 1990 murder of Foreign Minister Robert Ouko named Biwott as a suspect,” though “a Kenyan inquiry later determined insufficient evidence to press charges”. The stain never fully lifted.

Goldenberg and Mega-Corruption

Another major controversy of the Moi era that touched Biwott was the Goldenberg Affair – a massive corruption scandal in the early 1990s involving fictitious gold and diamond exports that defrauded Kenya of hundreds of millions of dollars. While the scheme was engineered primarily by businessman Kamlesh Pattni (with alleged backing from top officials), Biwott’s name surfaced as one of the beneficiaries of the loot. He was not publicly implicated when the scandal first broke in 1993, but a later Judicial Commission of Inquiry (2003–2005) under Justice Bosire revisited Goldenberg in depth. In its report, the Bosire Commission listed Biwott among a dozen individuals who should be investigated or prosecuted for the affair. It was alleged that as a powerful minister close to Moi, Biwott facilitated or at least knew of the siphoning of public funds via fake export compensation payments to Goldenberg companies.

Biwott, predictably, denied involvement. And indeed, like in other cases, legal accountability proved elusive. In 2006, Kenya’s government attempted to charge a few Goldenberg suspects, but some – including Biwott – obtained court orders blocking prosecution, arguing that evidence against them was hearsay or that they had been exonerated by earlier probes. By 2010, no major figure apart from Pattni had faced trial. Thus, while Goldenberg cemented the narrative of the Moi regime’s corruption, Biwott once again emerged formally unscathed. Still, the stench of Goldenberg added to Biwott’s notoriety. It was part of why foreign governments like Britain lumped him in with the most corrupt officials when imposing visa bans. To the public, Goldenberg was one more chapter where Biwott’s name came up when discussing how Kenya was economically pillaged in the 1990s. He became, in effect, a symbol of high-level graft – even absent a conviction.

The “Bull of Auckland” and Personal Scandals

Not all of Biwott’s controversies were of global import; some were peculiar, almost lurid footnotes that nonetheless fed the legend of the “Total Man.” One such incident earned Biwott the derisive nickname “The Bull of Auckland.” The name refers to an alleged sexual assault involving Biwott in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1990. Biwott was part of President Moi’s entourage to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in New Zealand that year. As the story goes, one morning in his Auckland hotel, Biwott indecently exposed himself to (or attempted to sexually assault) a hotel housekeeper who had come to service the room. The commotion led to Biwott being quietly whisked out of New Zealand (effectively deported) to avoid a diplomatic scene. For years this embarrassing episode was kept under wraps in Kenya – it was never reported in the controlled press. However, whispers circulated among diplomats and opposition figures. In 1995, fiery opposition MP James Orengo – under parliamentary privilege – brought it up on the floor of the House, cheekily referring to Biwott as the “Bull of Auckland”. The Hansard record quotes Orengo alluding to “the time when the Bull of Auckland, or rather Hon. Biwott…” tried to speak in the House but was rebuffed to the backbenches. This was a rare public hint of the scandal. The moniker stuck in political folklore, painting a rather unflattering image of Biwott’s alleged misconduct abroad.

Biwott never publicly addressed the Auckland incident. As with most personal controversies, he let silence and the passage of time bury it. But the “Bull of Auckland” tag encapsulated another aspect of Biwott’s reputation – a man seen as regarding himself above the law, whether in financial dealings or personal behavior. It also showed that even his fellow politicians were aware of his misdeeds but often feared raising them except obliquely. Only the bravest (or those with nothing to lose) like Orengo dared taunt him in public, and even then with euphemism.

“Total Man” and Public Silence

Throughout the storms of allegations, Biwott’s public posture was one of unyielding silence or outright dismissal. He granted extremely few media interviews in his lifetime. One of the only times Kenyans heard him speak at length about the accusations was during the 2005 parliamentary inquiry, where he angrily denied murdering Ouko. Otherwise, Biwott preferred official statements through lawyers or terse press releases. He seemed to embody the dictum that state secrets and personal secrets must be guarded at all cost. This reticence only heightened the mystique around him. The less he said, the more fascinated (and fearful) the public grew. In fact, by the late 1990s Biwott was such a mythical figure that popular imagination attributed all manner of sinister powers to him – from the ability to make opponents “disappear” to the ownership of a mysterious briefcase supposedly containing sensitive files (or even poisons). The satirical print media sometimes caricatured him as a cloaked, shadowy machinator at President Moi’s side.

Meanwhile, Biwott doubled down on cultivating a positive legacy to counter the negative press. He engaged in philanthropy, funding schools (such as the Maria Soti Girls’ Secondary School, named after his mother) and health projects in his home area. During the 1990s and 2000s, he also sued and often won against media that accused him of corruption, reinforcing an image of a man whom the courts, at least, found favor with. His supporters argued that Biwott was a victim of rumormongering and jealousy, noting that “nothing was ever proved” against him despite numerous probes. Indeed, Biwott liked to remind people that he was never convicted of any crime – a factual point that he felt vindicated him. However, to critics, that was merely evidence of his ability to manipulate the system. Biwott remained, in the court of public opinion, guilty until proven innocent – and proof was hard to come by when witnesses feared testifying and evidence had a way of vanishing.

Fall from Grace: Biwott in the Post-Moi Era

With President Moi’s constitutionally mandated retirement and KANU’s defeat in the 2002 elections, Nicholas Biwott’s official grip on power came to an abrupt end. The incoming government of President Mwai Kibaki (2003–2007) campaigned on an anti-corruption, reform platform that directly targeted the misdeeds of the Moi era. For the first time in over two decades, Biwott found himself outside the circles of state power. The transition was not just political but generational: many of Biwott’s contemporaries exited the scene, and a new cohort of leaders (some of whom had been dissidents he once suppressed) took the helm.

Initially, Biwott attempted to remain relevant within the opposition. He retained his parliamentary seat in 2002 as a KANU MP for Keiyo South, even as KANU lost the presidency. In Parliament, he cut a lonely figure on the opposition benches – the once-dreaded Total Man now in unfamiliar territory. Tellingly, it was under Kibaki’s government that the inquiries into Goldenberg and Ouko were relaunched, signaling that Biwott would no longer be shielded by State House. Biwott fought these investigations tooth and nail (with some success in the courts, as noted). But the mere fact that he could be publicly investigated was a sign of his diminished clout.

KANU itself went through turbulence after Moi’s exit. In 2005, as KANU struggled in opposition, Biwott audaciously challenged Uhuru Kenyatta (the son of founding president Jomo Kenyatta) for chairmanship of the party. It was an attempt by the old guard to reclaim KANU’s leadership. Biwott lost the party elections to the younger Kenyatta, reflecting a generational shift. Undeterred, Biwott broke away and founded his own party, the National Vision Party (NVP), in 2008. The NVP was a minor vehicle, but Biwott used it to contest one more election: in 2007 he sought re-election as MP under NVP. That year, however, a massive anti-establishment wave (the ODM wave) swept the Rift Valley, and Biwott was resoundingly defeated in Keiyo South – losing the seat he had held since 1979. At age 67, “Total Man” finally tasted electoral loss. Many saw it as the end of an era. Biwott quietly accepted defeat and did not contest the outcome.

He largely receded from the limelight thereafter. In 2013, at 73 years old, Biwott made a quixotic attempt at a comeback, running for the newly created Elgeyo-Marakwet Senate seat. He lost once again, finishing far behind younger competitors. That was his final bow in politics. The once feared kingmaker was now a statesman emeritus of sorts – occasionally appearing at state functions or Moi family events, but with no active role. Journalists who encountered him in those later years noted that Biwott remained as taciturn as ever, giving only polite smiles and cryptic comments.

Biwott’s waning influence was underscored by legal developments: some pending cases against him fizzled out, and he was never jailed or penalized, but neither did he wield the power to halt such cases by fiat as he might have in the past. For instance, when the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission was set up in 2008 to examine historical injustices, there were calls for figures like Biwott to testify about 1980s abuses. In another time, he might have scuttled that; in this new era, he simply ignored it, and the process moved on without him.

On the business front, Biwott’s interests continued, albeit more under management by family and professional teams. He remained exceedingly wealthy, but he kept an even lower profile in business than in politics. Some of his assets were sold or restructured (Kenol-Kobil, for example, eventually was sold to a multinational in 2019 after his death). By the 2010s, Biwott was spending more time with family and pursuing philanthropy – he funded a large modern church in Eldoret and continued supporting his mother’s namesake girls’ school.

Ultimately, Nicholas Biwott’s “Total” influence proved finite. Once the patron (Moi) was gone, the edifice of power that Biwott had built swiftly crumbled. Observers of Kenyan politics often remark how decisively Biwott’s clout vanished after 2002: a man who once inspired dread could barely win a local election a few years later. This is a testament to how centrally his authority had depended on Moi’s presidency. Without the shield of state power, Biwott the individual was exposed, and Kenyans – now empowered by a freer media and new leadership – were eager to consign the dark days of the “Total Man” to history.

Legacy and Memory: The Many Faces of Nicholas Biwott

When Nicholas Biwott died on July 11, 2017, at Nairobi Hospital aged 77, reactions across Kenya were mixed and complex. Here was a man who had been at the commanding heights of power, wealth, and mystery – now gone, taking his secrets with him. In death as in life, Biwott commanded both praise and scorn, often in equal measure.

State eulogies were glowing. President Uhuru Kenyatta eulogized Biwott as “a true patriot and a dependable leader who served the country with devotion,” highlighting his contributions to Kenya’s development. Given Biwott’s role in founding institutions like KEMRI and boosting commerce, some of this praise was grounded in fact. Former President Daniel arap Moi mourned his longtime ally deeply; Moi’s family and network lauded Biwott’s loyalty and effectiveness. At Biwott’s burial in Elgeyo-Marakwet, speakers painted him as one of the architects of Kenya’s stability, noting that he had been pivotal in the country’s first peaceful transfer of power (from Kenyatta to Moi in 1978). Raila Odinga – once an opposition nemesis – acknowledged Biwott’s role at a “critical moment” in ensuring continuity in Kenya, despite their political differences. Such comments reflect a recognition that Biwott was part of Kenya’s state-building narrative, for better or worse. They remember him as an experienced technocrat: a man who knew every corner of the nation, having served in three presidents’ governments (Jomo Kenyatta’s, Moi’s, and briefly Mwai Kibaki’s). To admirers, Biwott’s work ethic and pragmatism were to be celebrated – “he spoke less and did more…he epitomized action,” said long-time friend Pius Ngugi, describing Biwott as a man who focused on getting things done.

Historians and political analysts offer a more nuanced legacy. Many view Biwott as the personification of the Moi era: authoritarian, secretive, but also shrewd in statecraft. His political biography, one columnist wrote, “might well be a commentary of Daniel arap Moi’s rule”. Indeed, Biwott’s career mirrors the trajectory of Kenya from the hopeful 1960s, through the autocratic 80s, to the reformist 2000s. Analysts credit him with mastering the art of “state capture” long before the term was popular – by interlinking business, politics, and security, he helped Moi concentrate power and dismantle the influence of Kenyatta-era elites. For instance, Biwott was instrumental in sidelining the old Kikuyu elite after 1978, thereby reorienting state patronage to new networks (like his and Moi’s Kalenjin cohorts). This re-balancing of power – though done undemocratically – arguably prevented ethnic hegemony and gave regions like Rift Valley greater stake in government. At the same time, Biwott is remembered as a chief architect of the repression and economic mismanagement that plagued the 1980s-90s. He is indelibly associated with the worst excesses of single-party rule: political detentions, unsolved murders, torture of dissidents, and grand corruption scams. The Akiwumi Commission on 1990s tribal clashes, the Truth Commission on historical injustices – all allude to “powerful individuals” behind the scenes, and Biwott’s name inevitably surfaces in such discussions, even if not always explicitly.

To the Kenyan public, especially those who came of age during the Moi regime, Biwott remains a almost legendary figure – the poster child of the shadowy power broker. This is evident in the enduring fascination with him in media and culture. His nickname “Total Man” is still used in everyday political talk to describe someone with overwhelming, if opaque, influence. Yet that term also carries negative connotations: it evokes impunity. Even today, headlines recall him as “Kenya’s most feared power broker” or “the man who made politicians tremble”. For many ordinary Kenyans, Biwott’s legacy is one of fear and unanswered questions. They remember the climate of the late 80s and 90s when Biwott’s name was whispered in taverns as someone you didn’t cross – when assassinations like Ouko’s went unresolved and billions disappeared, all with no accountability. In that sense, Biwott symbolizes the dark side of Kenya’s post-colonial state, a reminder of how unchecked power can corrode institutions.

And yet, with the passage of time, some Kenyans have begun to reassess figures like Biwott more dispassionately. A new generation, removed from the immediate pain of the Moi days, can analyze Biwott as a historical figure. They ask: How did he accumulate so much power? What does his life tell us about patronage politics? On this, scholars note that Biwott’s success lay in being the ultimate loyal lieutenant. He was fiercely loyal to Moi, never showing open ambition for the top job himself (despite the “King in Waiting” moniker). In African politics, such loyalty can be rewarded with enormous delegated power. Biwott wielded that delegated authority to the hilt. Furthermore, his technocratic skills – rare among politicians of his generation – made him genuinely useful in policy execution, which reinforced Moi’s dependence on him.

In summing up Nicholas Biwott’s legacy, one might say it is profoundly dualistic. He was both a nation-builder and an emblem of Kenya’s era of authoritarian excess. His contributions to development (infrastructure, businesses, regional cooperation) stand alongside accusations of destroying others’ careers and lives. In the end, even his critics concede he was effective – if in a Machiavellian way. As the Business Daily aptly wrote, Biwott “goes down in history as one of the most maligned politicians, whose name was often dragged into mega scandals, but nothing was ever proved against him in a court of law.” This quote encapsulates the enigma of Nicholas Biwott: a man forever shadowed by intrigue, undefeated by legal challenge, and unforgettable in the annals of Kenyan history.

Sources:

- Biwott, N. (2017). Personal Website: Early Life, Timeline, Businessman.

- Business Daily Africa. (2017). “Ex-minister Biwott dies in Nairobi hospital.”

- Pulselive Kenya. (2017). “Why Nicholas Biwott was called ‘Total Man’…”

- Kenyans.co.ke. (2019). “Moi Era’s Infamous Dam Scandal…”

- News24. (2005). “Ex-minister suspected of murder.”

- VOA News. (2009). “Britain Denies Visas to Two Prominent Kenyan Politicians.”

- The Standard. (2020). “Nicholas Kipyator arap Biwott: Power and mystery personified.”

- Diaspora Messenger. (2021). “Richest People in Kenya – Nicholas Biwott.”

- Fatuma’s Voice (blog thread). “Remember The Total Man? Nicholas Biwott.”