In 1963, Julius Nyerere made an extraordinary offer: he would delay Tanganyika’s independence if Kenya and Uganda agreed to a political federation. It was a bold, almost reckless act of Pan-African faith. But it failed. The dream of a united East Africa—so close to reality that leaders were negotiating cabinets and constitutions—was dead before it began.

What followed was decades of regional cooperation without union, bureaucratic alliances without political unity, and a ghost that still haunts the continent’s most integrated neighborhood. This is the story of how the East African Federation nearly happened, why it didn’t, and what its failure reveals about the limits of postcolonial idealism.

Empire’s Convenient Glue

The irony is brutal: the idea of East Africa as a single political and economic unit was not born of African solidarity, but of British administrative convenience.

By the 1920s, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika were effectively stitched together by empire. They shared railways, harbors, customs tariffs, postal services, air travel networks, and even higher education—anchored by Makerere University in Kampala. The Colonial Office ran them with a semi-coordinated logic, encouraging inter-territorial bodies like the East African High Commission.

The infrastructure of federation existed. The ideology didn’t.

Local traders and customers did not always call these coins by their English names. Instead, they used Swahili terms such as “Katongole Moja” for ten cents, “Nusu Rupee” for half a rupee, “Shilingi Moja” for one shilling, “Sumuni” for fifty cents, “Anna Mbili” for two annas, “Ndururu” for five cents, and “Hela Moja” for one cent. These Swahili names helped people of different language backgrounds understand values and make change without needing to speak English.

Nyerere’s Federation Fever

Julius Nyerere, leader of Tanganyika and future father of Tanzania, was East Africa’s loudest federalist. He saw the danger of newly independent African states retreating into nationalism and becoming irrelevant on the world stage. His vision was clear: unite now or become pawns later.

Nyerere offered his country’s independence as a bargaining chip. Let’s federate first, he said—then raise the flag. His urgency was real. Once the logic of sovereignty took hold, it would be hard to undo.

But the offer was met with polite evasion.

Uganda’s Suspicion

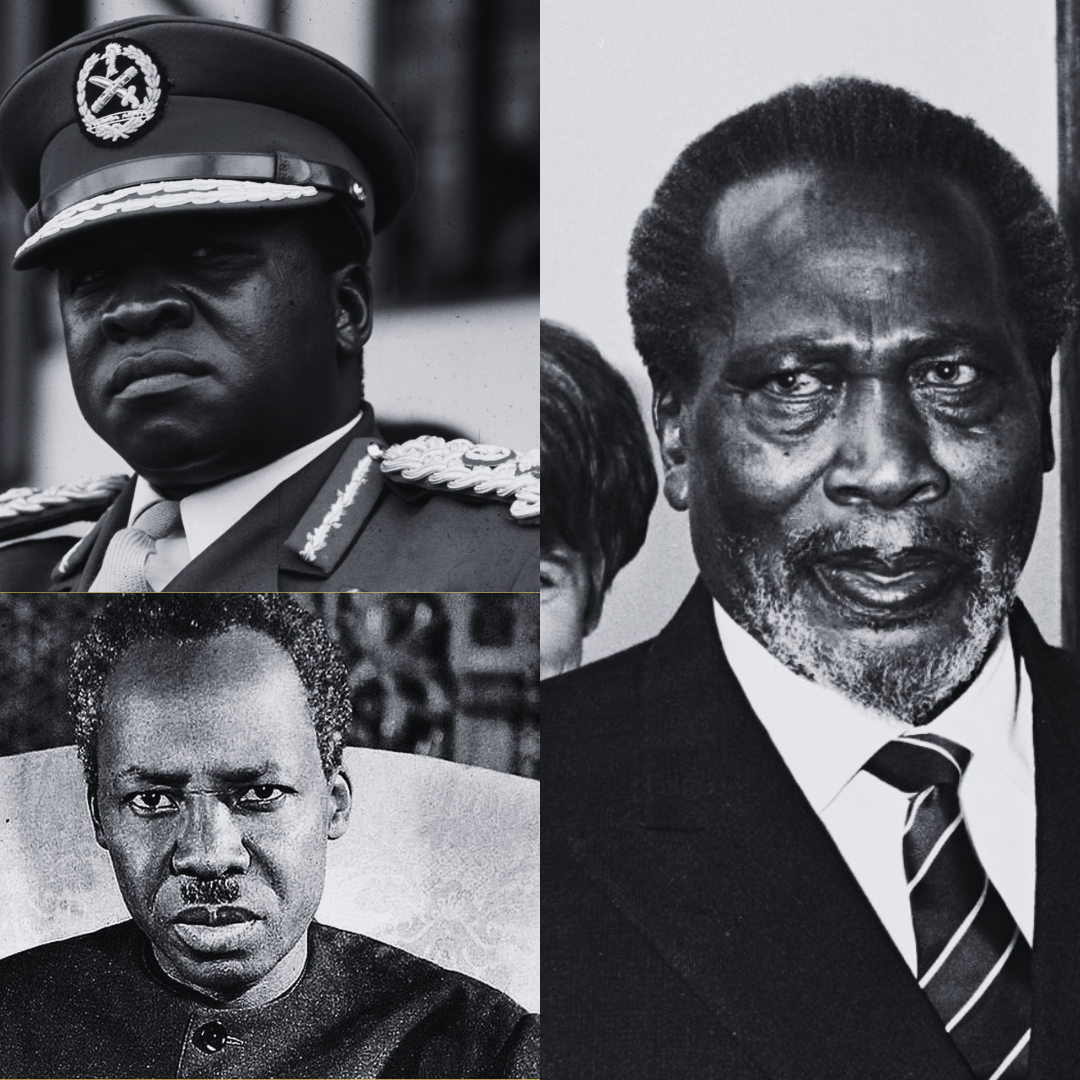

Uganda’s leadership, under Milton Obote, was skeptical. Their hesitation had layers.

First, there were internal complications. Uganda was (and remains) a mosaic of ethnic and political fault lines, none more contentious than the relationship between the central government and the Kingdom of Buganda. To join a federation before resolving its own domestic fractures seemed dangerous.

Second, there was a legitimate fear of Kenyan dominance. Kenya’s white settlers, commercial infrastructure, and entrenched racial economy raised alarms in Kampala. Would a federation make Uganda a junior partner in a Kenya-led bloc?

Kenya’s Calculus

Kenya, under Jomo Kenyatta, played the game slower.

The country had just emerged from the trauma of Mau Mau, the detention camps were still fresh in the national psyche, and the settler question had not been resolved. Kenya’s elite needed time to consolidate power, reassure capital, and negotiate land transitions from Europeans to Africans.

A federal union with two poorer neighbors, at a moment when Kenya still had white highlands and Indian merchants to deal with, was a hard sell. Unity could wait.

The Colonial Poison Pill

Lurking behind all this was Britain.

The British Empire had encouraged regional integration as long as it served imperial management. But when it came to African-led federation, the same empire became cautious. London feared that a powerful East African bloc would become harder to manipulate or might lean too far left—especially under the ideological influence of Nyerere.

Instead of pushing for federation, British officials began prioritizing bilateral handovers. Each territory would receive its own independence, with its own constitution and its own path.

The federation dream was quietly sidelined in Whitehall.

A Federation Without a State

By 1963, the momentum had died. Kenya achieved independence on its own terms. Uganda had done so a year earlier. Tanganyika, burned by the rejection, moved toward a different experiment: union with Zanzibar after the 1964 revolution, forming Tanzania.

The infrastructure of integration remained. The East African Common Services Organisation (EACSO) persisted. It ran the railways, posts, harbors, airlines, and more. But it was a federation in everything except the one thing that mattered: political power.

It was a ghost government—efficient, technocratic, and utterly non-sovereign.

Collapse of the East African Community (EAC), 1977

Eventually, even this ghost died. By the mid-1970s, tensions between the member states had become toxic.

Idi Amin’s coup in Uganda made regional diplomacy nearly impossible. Kenya leaned capitalist, Tanzania leaned socialist, and Uganda was descending into dictatorship. The ideological split between Kenyatta and Nyerere had widened. Cross-border accusations flew. Budget contributions were delayed. Joint assets became bones of contention.

In 1977, the East African Community collapsed entirely. Border posts were closed. The common services were dismantled. Trains stopped. A shared airline grounded. Even stamps became nationalized.

The region had moved from shared dreams to silent divorce.

The Lingering Ghost

Despite its collapse, the idea of East African unity never died. It simply mutated.

In 2000, the East African Community (EAC) was revived—with Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania as founding members. Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo later joined. But this was a different animal: a trade bloc, not a federation. A regional bureaucracy, not a sovereign merger.

The 21st-century EAC has a common market, a customs union, even a vision for a common currency. But the political union remains distant—always proposed, never implemented.

Why It Failed, Why It Still Matters

So why did the original East African Federation fail?

Because timing is everything. The moment for unity was before independence, not after. Once sovereignty was attained, it became too precious to surrender. Leaders needed to build their own states before they could build a regional one. The pressures of internal nation-building—ethnic balancing, land reform, political legitimacy—were simply too great.

But the ghost lingers because the logic remains sound. Fragmented African states face common problems: weak currencies, duplicated infrastructure, food insecurity, and foreign dependence. A united bloc could offer scale, bargaining power, and resilience.

The East African Federation was a missed opportunity. But perhaps not a lost cause.

Read Next: